csprimer-computersystem-concept5

csprimer-operatingsystem-concept1

-

(143) How a Single Bit Inside Your Processor Shields Your Operating System’s Integrity - YouTube excellent animated video teaching low level

assembly

-

Ray Toal → ray has tons of useful resources Clean Code

-

x64 NASM Cheat Sheet → useful Chromium OS Docs - Linux System Call Table → systemcall to register cheatsheat Assembly - System Calls → tutorialspoint

x86 and amd64 instruction reference → damn

project : hackclub/some-assembly-required: 📖 An approachable introduction to Assembly. some-assembly-required/guide/resources.md at main · hackclub/some-assembly-required

-

debugger gef and pwndbg unix-gdb

x64 NASM cheat sheet

Registers

| 64 bit | 32 bit | 16 bit | 8 bit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (accumulator) | RAX | EAX | AX | AL |

| B (base, addressing) | RBX | EBX | BX | BL |

| C (counter, iterations) | RCX | ECX | CX | CL |

| D (data) | RDX | EDX | DX | DL |

RDI | EDI | DI | DIL | |

RSI | ESI | SI | SIL | |

| Numbered (n=8..15) | Rn | RnD | RnW | RnB |

| Stack pointer | RSP | ESP | SP | SPL |

| Frame pointer | RBP | EBP | BP | BPL |

; ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

; Writes "Hello, World" to the console using only system calls. Runs on 64-bit Linux only.

; To assemble and run:

;

; nasm -felf64 hello_linux.asm && ld hello_linux.o && ./a.out

;

; Derived from the NASM tutorial at https://cs.lmu.edu/~ray/notes/nasmtutorial/

; ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

global _start

section .text

_start: mov rax, 1 ; system call for write

mov rdi, 1 ; file handle 1 is stdout

mov rsi, message ; address of string to output

mov rdx, 13 ; number of bytes

syscall ; invoke operating system to do the write

mov rax, 60 ; system call for exit

xor rdi, rdi ; exit code 0

syscall ; invoke operating system to exit

section .data

message: db "Hello, World", 10 ; note the newline at the end

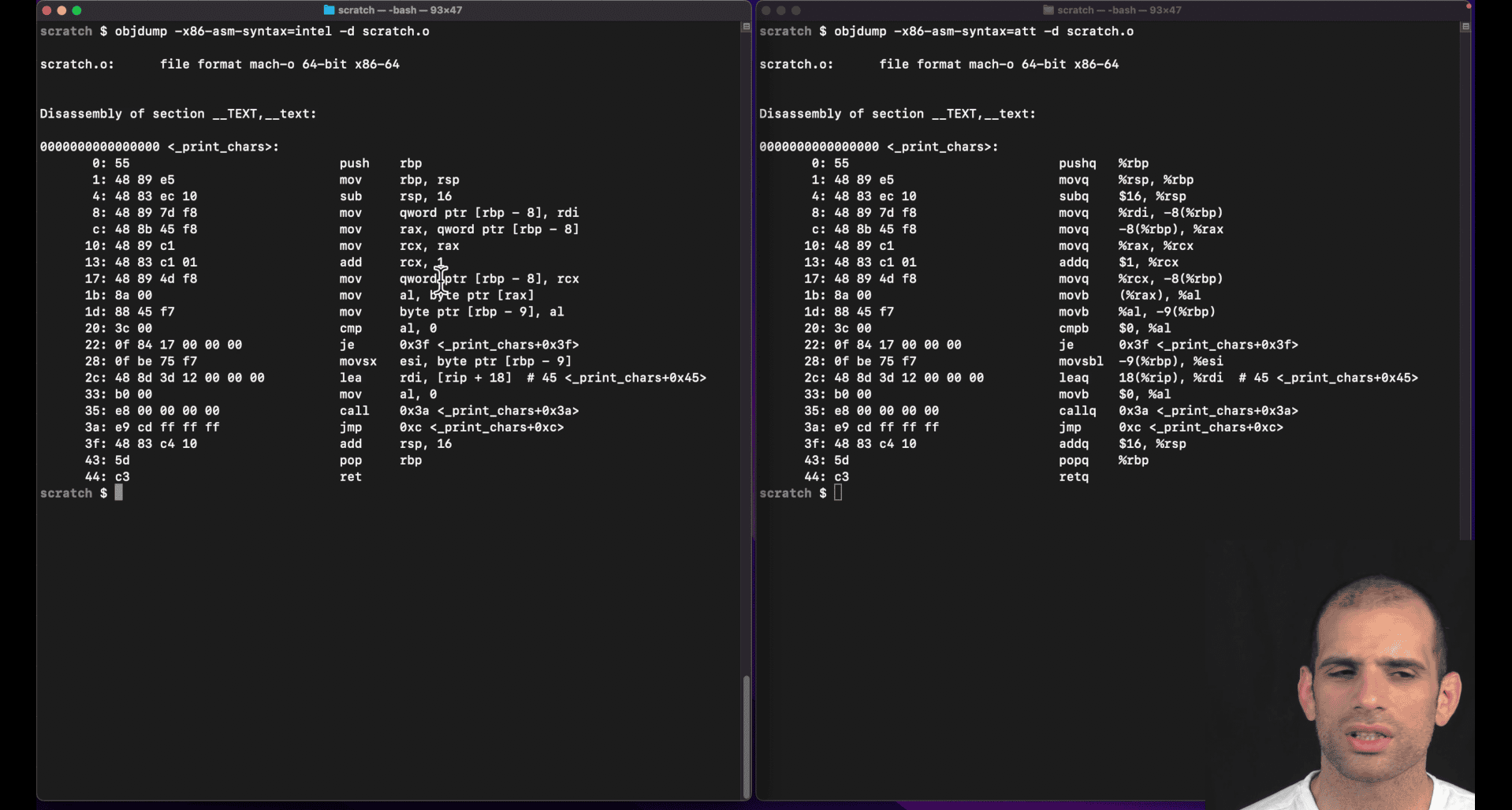

objdump -d file.o → show the code exactly , better than hexdump , as -d is for asm

48 31 ff xor %rdi,%rdi`` use less bytes than move`

more efficient?

output are from right to left as arch form intel

att Display instruction in AT&T syntax intel Display instruction in Intel syntax

objdump -Mintel,x86-64 -d hello_linux.o → turn back intel to left to right

ld → link file for becoming excutable

language

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <_start>:

0: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

5: bf 01 00 00 00 mov edi,0x1

a: 48 be 00 00 00 00 00 movabs rsi,0x0

11: 00 00 00

14: ba 0d 00 00 00 mov edx,0xd

19: 0f 05 syscall

1b: b8 3c 00 00 00 mov eax,0x3c

20: 48 31 ff xor rdi,rdi

23: 0f 05 syscall

- b8 is the r0 register , there is 7 register out there , b8 to bf all the r0 to r7 (32 bits eax to edi)

use file x.file to check what type of file it is

lldb , breakpoint , → run → register eax → step → or reg read (show all register)

you can config register in different format

Whats the difference between Intel and ATT assembly syntax

left intel, right : att(unix)

att show more info, from right to left though

att: q→quartword

Intel vs AT&T Syntax Differences

AT&T syntax (used by GNU assembler as, gcc, objdump):

- Operand order:

source, destination(opposite of Intel) - Register prefixes:

%before registers (%rax,%rdi) - Immediate prefixes:

$before constants ($42,$0x100) - Memory addressing:

(%rax)for dereference,4(%rax)for offset - Size suffixes:

b(byte),w(word),l(long/dword),q(quad/qword)

Intel syntax (used by NASM, MASM, Intel docs):

- Operand order:

destination, source(more intuitive) - No prefixes:

rax,rdi(no%) - No immediate prefix:

42,0x100(no$) - Memory addressing:

[rax],[rax+4] - No size suffixes: size inferred from operands

AT&T Size Suffixes Explained

| Suffix | Size | Example | Intel Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

b | 8-bit (byte) | movb %al, %bl | mov bl, al |

w | 16-bit (word) | movw %ax, %bx | mov bx, ax |

l | 32-bit (long) | movl %eax, %ebx | mov ebx, eax |

q | 64-bit (quad) | movq %rax, %rbx | mov rbx, rax |

Examples

AT&T:

movq $42, %rax # Move immediate 42 to rax

movl %eax, (%rbx) # Move eax to memory at rbx

addq $8, %rsp # Add 8 to rsp

subq %rdx, %rcx # Subtract rdx from rcxIntel:

mov rax, 42 # Move immediate 42 to rax

mov [rbx], eax # Move eax to memory at rbx

add rsp, 8 # Add 8 to rsp

sub rcx, rdx # Subtract rdx from rcxWhy AT&T Uses Suffixes

- Explicit sizing: Makes instruction size clear in source code

- Historical: AT&T syntax predates modern assemblers that infer sizes

- Consistency: Same suffix system across all instruction types

Tools and Syntax

- GNU tools (

gcc,objdump,gdb): Default to AT&T - NASM: Intel syntax

- GAS: Can use

.intel_syntaxdirective for Intel syntax - LLDB/GDB: Can switch between syntaxes with

set disassembly-flavor intel

Most Linux/Unix development uses AT&T syntax, while Windows development typically uses Intel syntax.

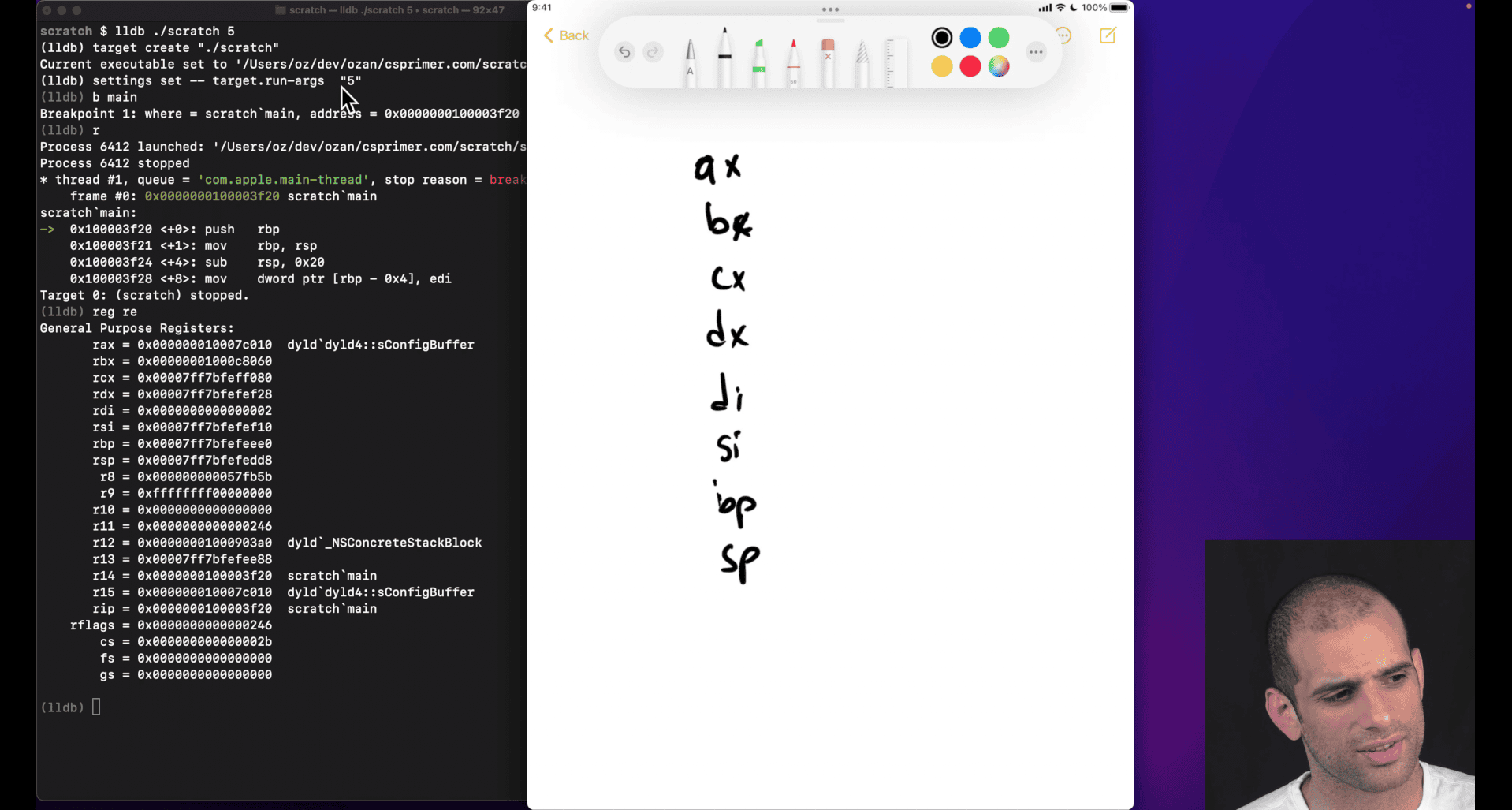

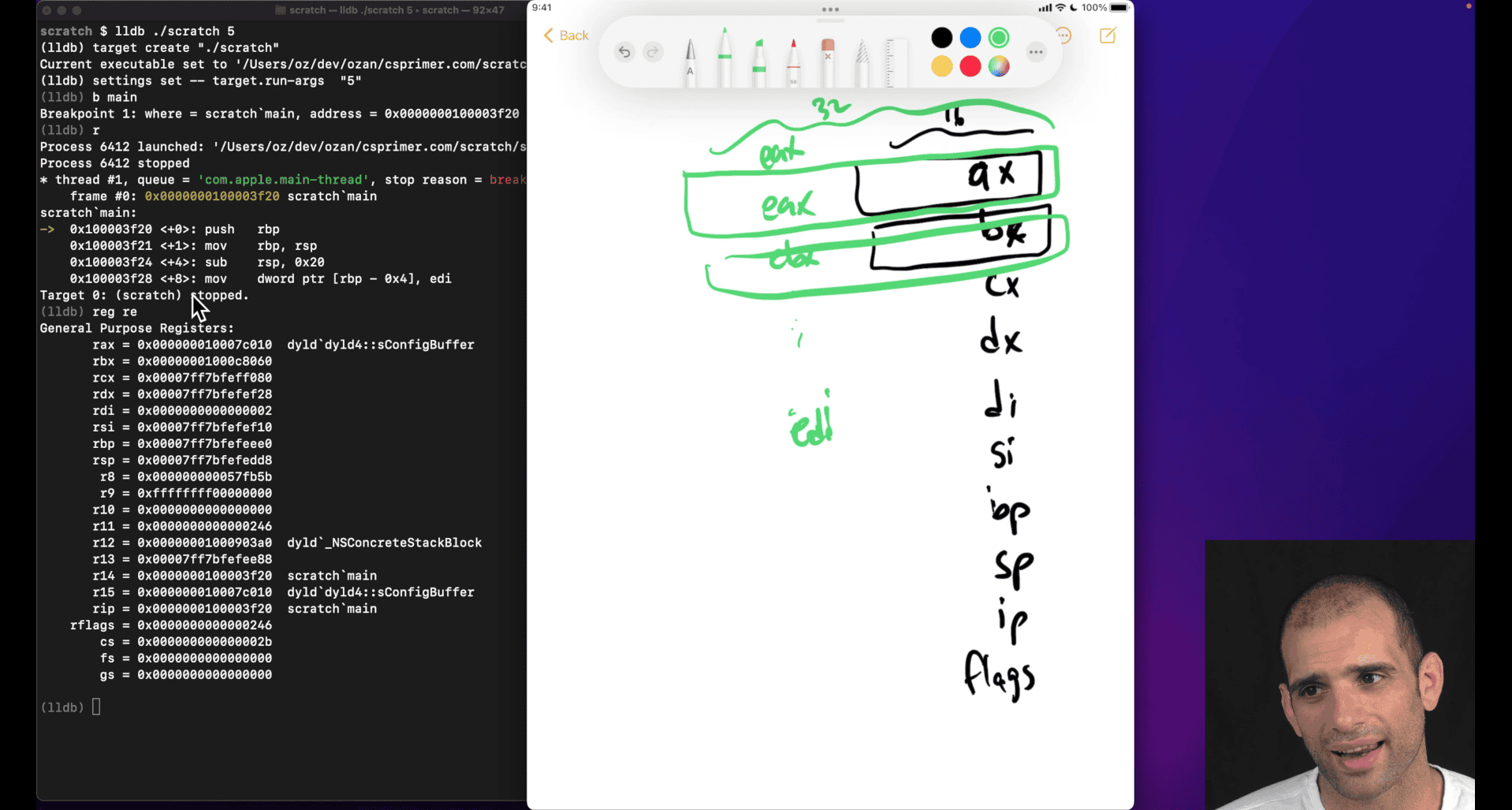

What are the general purpose registers in x8664

ax, bx , cx ,dx,di,si (legacy register) ah → half (less common) al → last (less common) di , si → , destination, source bp, sp → base pointer, stack pointer

bp→ top of the last stack frame (compiler don’t always update this value though)

ip → instruction pointer (store currently executing instruction)

flags → result of previous executing instruction, (overflow , last comparison situation etc)

inter doing ‘extend’ version register

smaller register will overflow (like adding ax to bx) even in larger physical register , just like making smaller btyes version why still here:

- smaller size

- compatible

rax → more extend from 32bits to 64 bits from eax

some case that doing 32bits register +-+*/ in 64 bits, higher bits will zero out, but 16 bits won’t WTF

cpu not able to do some out of order executions because it don’t know whether the extra bits need or not, zero out?

-

reg read --allin lldb -

calling convention → e.g unix , need to put return into rax

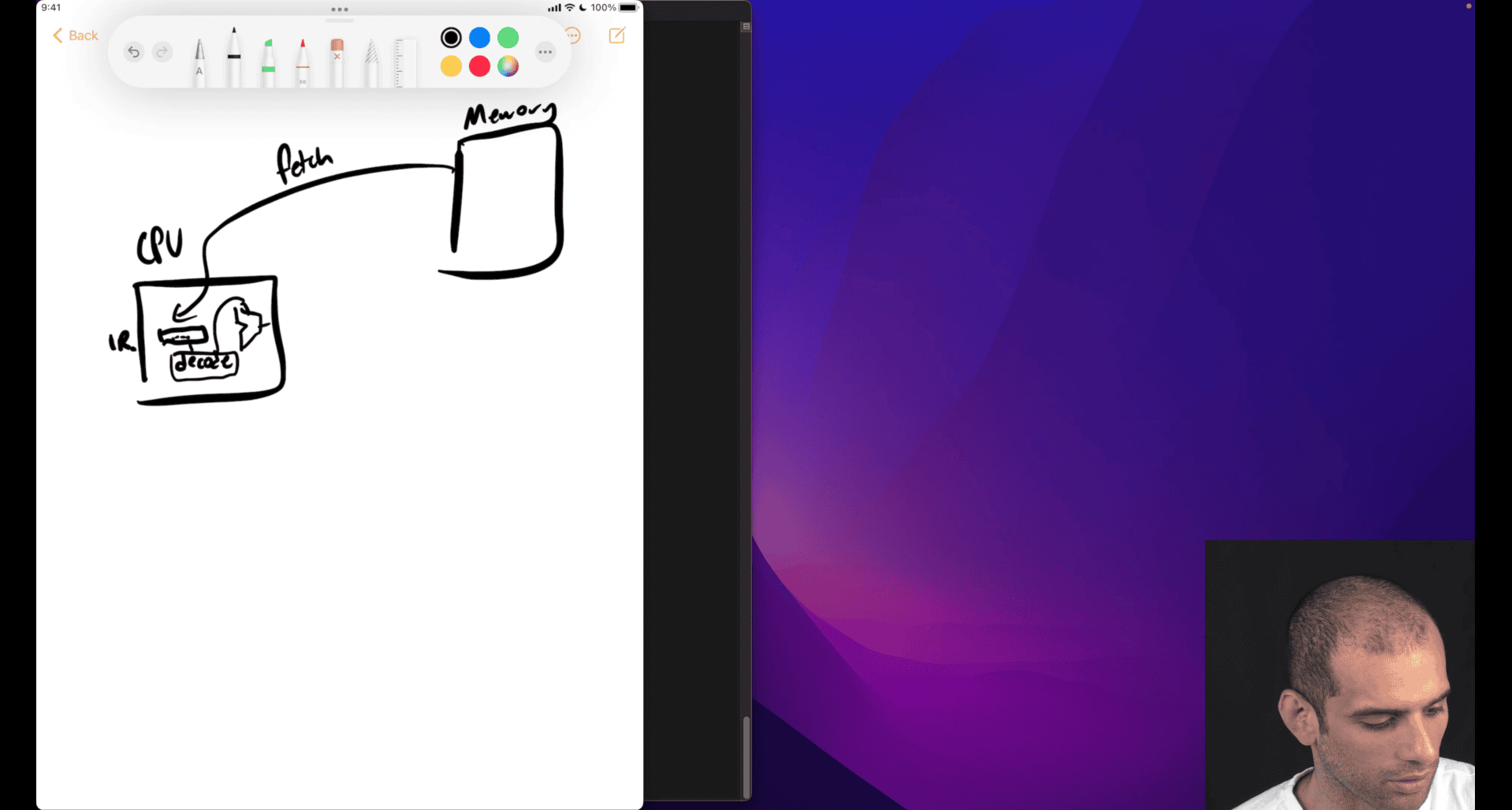

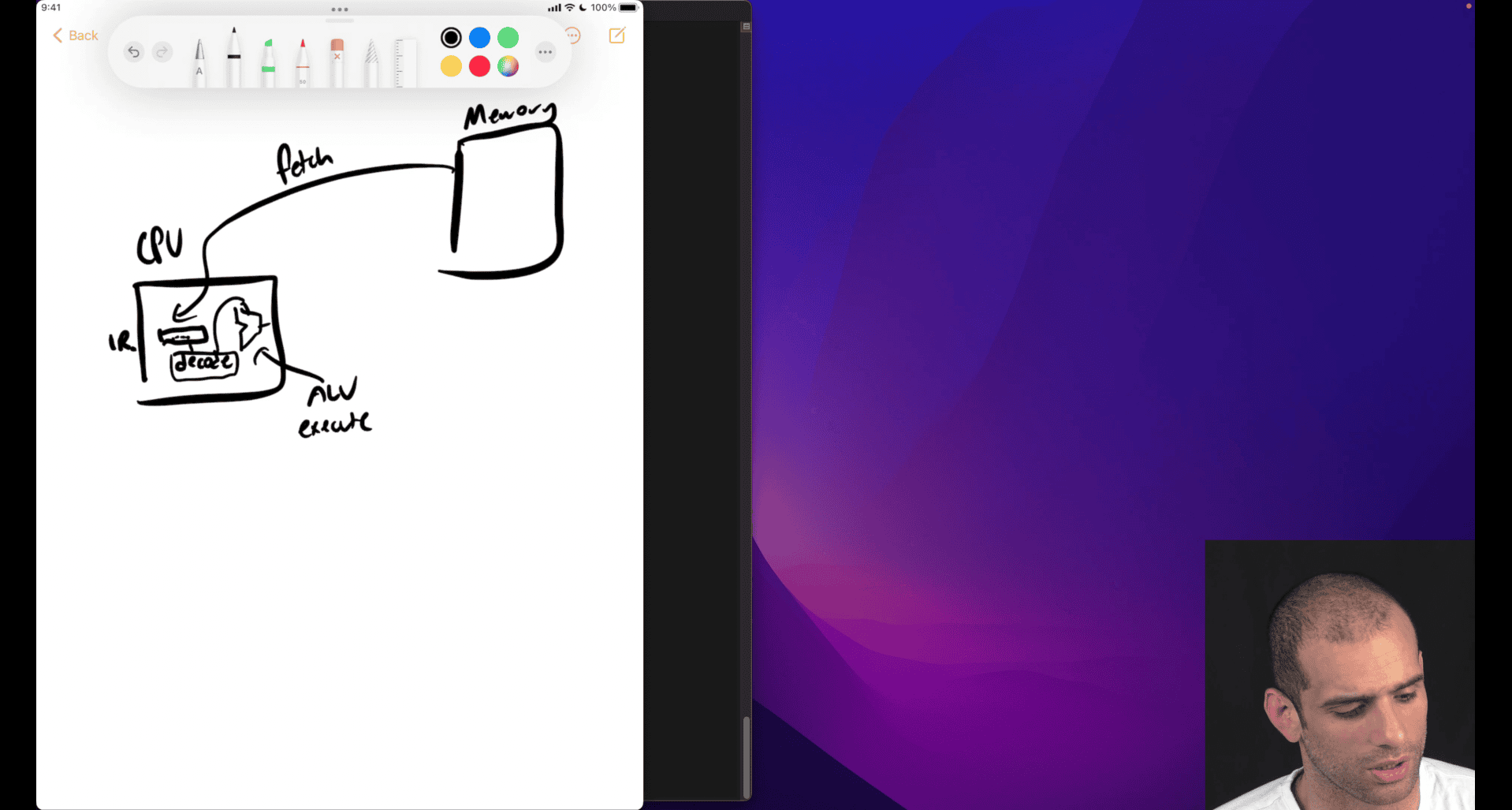

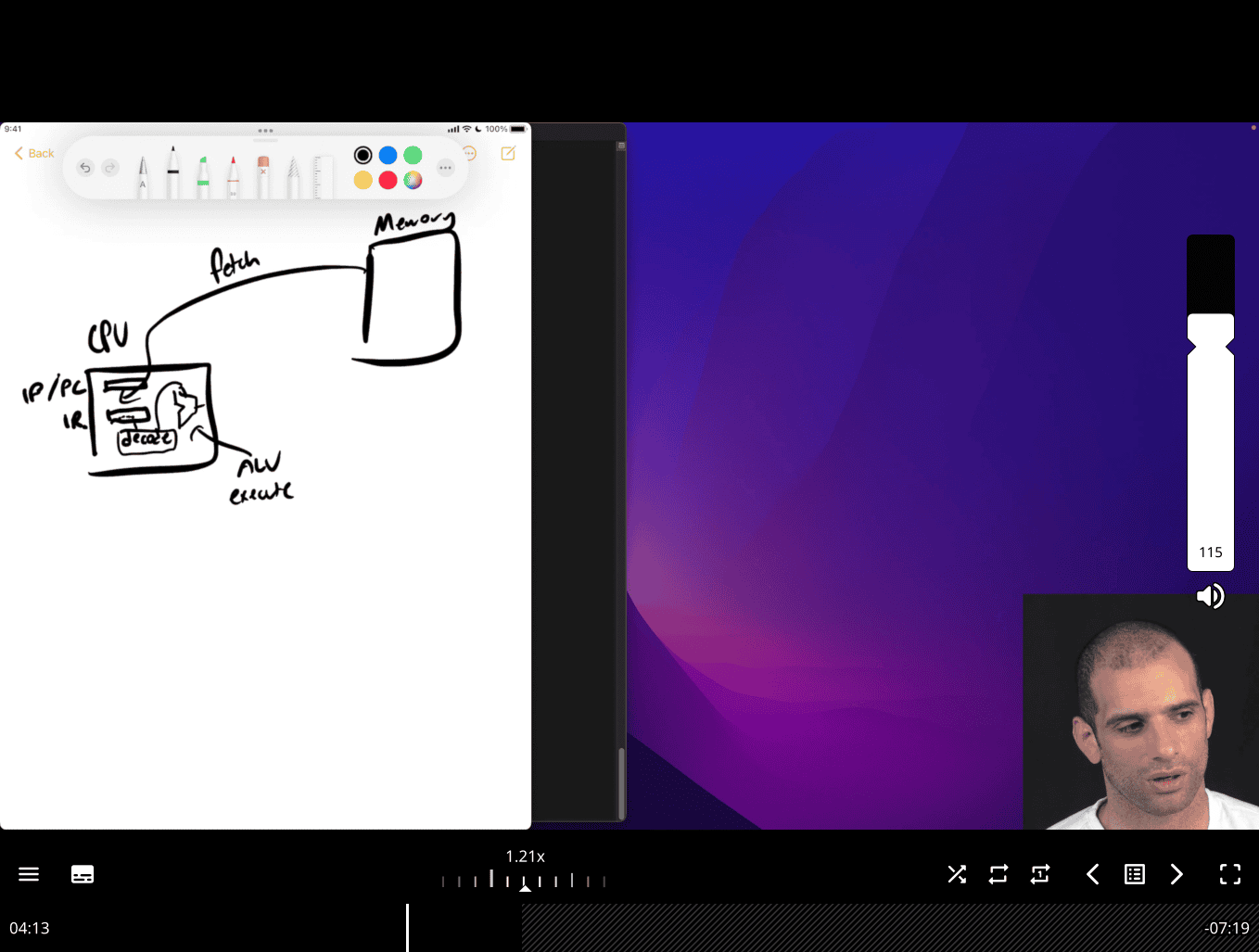

What is the fetch‑decode‑execute cycle?

Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle

The Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle is the fundamental process that CPUs use to execute machine instructions. It’s a continuous loop that processes instructions one at a time.

The Three Stages

1. Fetch (IF - Instruction Fetch)

- CPU reads the next instruction from memory

- Uses the Instruction Pointer (

%rip) to know where to fetch from - Loads instruction into the Instruction Register (IR)

- Increments

%ripto point to next instruction

2. Decode (ID - Instruction Decode)

- CPU analyzes the fetched instruction

- Determines:

- What operation to perform (opcode)

- Which registers to use (operands)

- What addressing mode to use

- How many bytes the instruction occupies

- Sets up control signals for execution

3. Execute (EX - Execute)

- CPU performs the actual operation

- Examples:

- Arithmetic/logic operations

- Memory read/write

- Register transfers

- Control flow changes (jumps, calls)

Visual Representation

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ FETCH │───▶│ DECODE │───▶│ EXECUTE │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ Read │ │ Analyze │ │ Perform │

│ from │ │ opcode │ │ operation│

│ %rip │ │ & ops │ │ │

└─────────┘ └─────────┘ └─────────┘

▲ │

└──────────────────────────────┘

Detailed Example

Let’s trace through: mov %rax, %rbx

Fetch Stage:

1. CPU reads instruction at address in %rip

2. Loads "mov %rax, %rbx" into Instruction Register

3. Increments %rip to next instruction

Decode Stage:

1. CPU recognizes "mov" opcode

2. Identifies source: %rax register

3. Identifies destination: %rbx register

4. Determines this is a register-to-register move

5. Sets up internal control signals

Execute Stage:

1. CPU reads value from %rax

2. Writes that value to %rbx

3. Instruction complete, ready for next cycle

Modern CPU Enhancements

Pipelining

Modern CPUs overlap these stages:

Cycle 1: [FETCH] [ ] [ ]

Cycle 2: [DECODE] [FETCH] [ ]

Cycle 3: [EXECUTE] [DECODE] [FETCH]

Cycle 4: [ ] [EXECUTE] [DECODE]

Cycle 5: [ ] [ ] [EXECUTE]

Superscalar Execution

- Multiple execution units work in parallel

- Can execute multiple instructions simultaneously

- Still follows fetch-decode-execute, but with parallelism

Out-of-Order Execution

- Instructions can execute out of program order

- CPU reorders instructions for better performance

- Maintains program correctness through dependency tracking

Special Cases

Control Flow Instructions

jmp label # Changes %rip directly

call func # Saves return address, then jumps

ret # Restores %rip from stackMemory Access

mov (%rax), %rbx # Fetch: instruction

# Decode: memory read operation

# Execute: read from memory, write to %rbxPerformance Implications

Fetch Bottlenecks:

- Cache misses slow down fetch

- Branch mispredictions waste fetch cycles

Decode Bottlenecks:

- Complex instruction formats take longer to decode

- Variable-length instructions (x86) complicate decoding

Execute Bottlenecks:

- Memory access latency

- Complex arithmetic operations

- Resource conflicts

In Assembly Programming

Understanding the cycle helps with:

Optimization:

## Good: Simple instructions decode faster

mov %rax, %rbx # Fast decode/execute

## Slower: Complex addressing modes

mov 8(%rax,%rcx,4), %rbx # More complex decodeDebugging:

%ripshows where CPU is fetching next- Understanding why certain instructions are slower

- Recognizing pipeline stalls

Quick Summary

- Fetch: Read instruction from

%rip - Decode: Figure out what to do

- Execute: Do the operation

- Repeat: Move to next instruction

This cycle runs billions of times per second in modern CPUs, with sophisticated optimizations to make it as fast as possible!

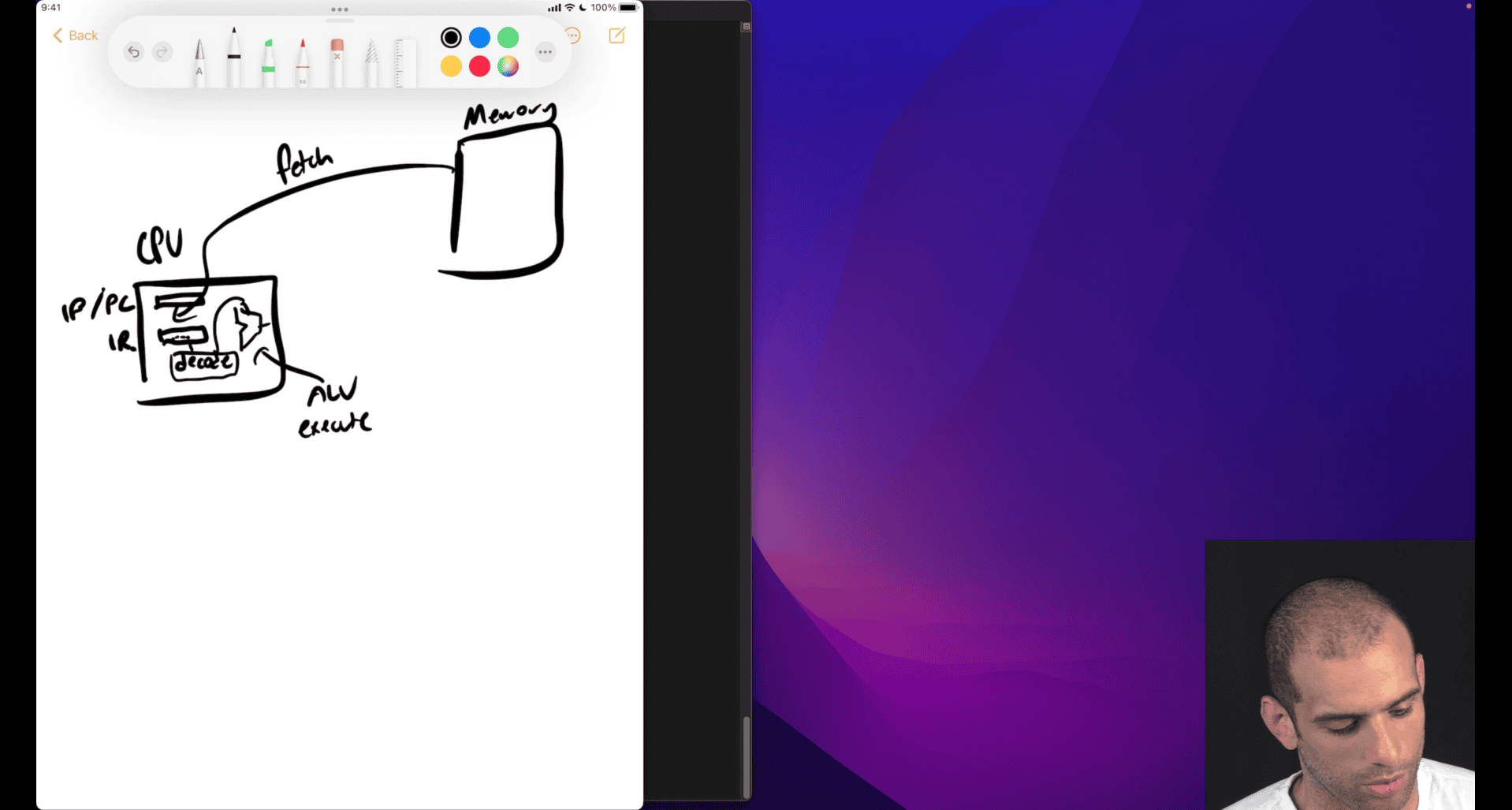

extra function like jump , function call , → advance movement then need to analysis what is the next move gonna do

store the next move in ip/pc → , instruction pointer ~= Pointer counter

- store the address , next thing to fetch , encode and execute

iterating → nature of the machine, e.g. cpu clocks

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int square(int n) { return n * n; }

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int n = atoi(argv[1]);

printf("%d x %d = %d\n", n, n, square(n));

}

0x555555555158 <+0>: pushq %rbp 0x555555555159 <+1>:

it only take 1 byte to pushq rbp in x86

s + reg re rip

rip = 0x0000555555555159 scratch main + 1

0x555555555159 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x55555555515c <+4>: subq $0x20, %rsp

movq → three bytes from +1 to +4

imagine movq is fetch 1 step

rip = 0x000055555555515c scratch`main + 4

rbp = 0x00007fffffffcac0

rsp = 0x00007fffffffcac0

0x55555555515c <+4>: subq $0x20, %rsp

rsp = 0x00007fffffffcaa0

from ac0 to aa0

rip = 0x0000555555555160 scratch`main + 8 (indicate subq = 4 bytes)

The System V AMD64 calling convention

What is a Calling Convention?

A calling convention is a standardized set of rules that defines:

- How function arguments are passed

- Which registers are preserved across function calls

- How return values are handled

- How the stack is managed

- Who (caller or callee) is responsible for cleanup

Why needed? Without conventions, different functions couldn’t call each other reliably. It’s like agreeing on a common “language” for function communication.

System V AMD64 Calling Convention (Unix Family)

This is the standard calling convention for 64-bit Linux/Unix systems (also used by macOS).

- window use slightly different convention → wiki x86 calling conventions

Argument Passing

| Position | Register | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | %rdi | First integer/pointer argument |

| 2nd | %rsi | Second integer/pointer argument |

| 3rd | %rdx | Third integer/pointer argument |

| 4th | %rcx | Fourth integer/pointer argument |

| 5th | %r8 | Fifth integer/pointer argument |

| 6th | %r9 | Sixth integer/pointer argument |

| 7th+ | Stack | Additional arguments pushed right-to-left |

Return Values

| Type | Register | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Integer/Pointer | %rax | Return value |

| Large structs | %rax | Pointer to return value |

| Floating point | %xmm0 | Return value |

Register Preservation

| Category | Registers | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Caller-saved | %rax, %rcx, %rdx, %rsi, %rdi, %r8, %r9, %r10, %r11 | Caller must save if needed |

| Callee-saved | %rbx, %rbp, %r12, %r13, %r14, %r15 | Callee must preserve |

- this is kind of important

- function caller , function callee

┌─────────────────┐ │ callee_function │ ← Currently executing (CALLEE) ├─────────────────┤ │ caller_function │ ← Waiting for callee to return (CALLER) ├─────────────────┤ │ main │ ← Waiting for caller to return

Examples

C Function Call:

int add(int a, int b, int c, int d, int e, int f, int g) {

return a + b + c + d + e + f + g;

}Assembly Implementation:

## Arguments passed in:

## %rdi = a, %rsi = b, %rdx = c, %rcx = d

## %r8 = e, %r9 = f, stack = g

add:

# Save callee-saved registers if needed

push %rbx

push %rbp

# Get 7th argument from stack

mov 24(%rsp), %rax # Skip saved %rbp, %rbx, return addr

# Add all arguments

add %rsi, %rdi # a + b

add %rdx, %rdi # + c

add %rcx, %rdi # + d

add %r8, %rdi # + e

add %r9, %rdi # + f

add %rax, %rdi # + g

# Return value in %rax

mov %rdi, %rax

# Restore callee-saved registers

pop %rbp

pop %rbx

retCalling the Function:

## Prepare arguments

mov $1, %rdi # 1st arg

mov $2, %rsi # 2nd arg

mov $3, %rdx # 3rd arg

mov $4, %rcx # 4th arg

mov $5, %r8 # 5th arg

mov $6, %r9 # 6th arg

push $7 # 7th arg on stack

call add # Call function

add $8, %rsp # Clean up stack (remove pushed arg)

## Result in %raxStack Management

Stack Layout During Function Call:

High Memory

↓

┌─────────────┐

│ Arg 7 │ ← %rsp + 24 (after call)

├─────────────┤

│ Return Addr │ ← %rsp + 16 (pushed by call)

├─────────────┤

│ Saved %rbp │ ← %rsp + 8

├─────────────┤

│ Saved %rbx │ ← %rsp (current)

└─────────────┘

Low Memory

Red Zone

- 128 bytes below

%rspare reserved - Functions can use this space without adjusting

%rsp - Useful for leaf functions (functions that don’t call others)

Floating Point Arguments

| Position | Register | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | %xmm0 | First floating point argument |

| 2nd | %xmm1 | Second floating point argument |

| 3rd | %xmm2 | Third floating point argument |

| 4th | %xmm3 | Fourth floating point argument |

| 5th+ | Stack | Additional FP arguments |

Common Patterns

Function Prologue:

my_function:

push %rbp # Save caller's base pointer

mov %rsp, %rbp # Set new base pointer

sub $16, %rsp # Allocate local variables

# Function body...Function Epilogue:

mov %rbp, %rsp # Restore stack pointer

pop %rbp # Restore base pointer

ret # Return to callerSystem Calls (Linux):

mov $1, %rax # sys_write

mov $1, %rdi # file descriptor

mov $message, %rsi # buffer

mov $13, %rdx # length

syscall # Make system callKey Points

- First 6 integer args:

%rdi,%rsi,%rdx,%rcx,%r8,%r9 - Return value:

%rax - Caller-saved: Use freely, but save if needed after call

- Callee-saved: Must preserve if used

- Stack alignment: Keep stack 16-byte aligned

- Red zone: 128 bytes below

%rspare safe to use

This convention ensures that C functions, assembly functions, and system calls can all work together seamlessly!

| Category | Registers | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Caller-saved | %rax, %rcx, %rdx, %rsi, %rdi, %r8, %r9, %r10, %r11 | Caller must save if needed |

| Callee-saved | %rbx, %rbp, %r12, %r13, %r14, %r15 | Callee must preserve |

- this is kind of important

- function caller , function callee

What Your Teacher Means

Your teacher is explaining the callee-saved register preservation rule. When a function (callee) wants to use a callee-saved register, it must:

- Save the original value (push to stack)

- Use the register for its own purposes

- Restore the original value (pop from stack) before returning

This ensures the caller gets back the same register values it had before the call.

The Rule in Action

❌ Wrong Way (Breaks the Convention):

callee_function:

mov $500, %rbx # Using callee-saved register

# ... do work with %rbx ...

ret # Returns without restoring %rbx!Problem: Caller’s %rbx value is lost forever!

✅ Correct Way (Follows Convention):

callee_function:

push %rbx # Save caller's %rbx value

mov $500, %rbx # Use %rbx for our purposes

# ... do work with %rbx ...

pop %rbx # Restore caller's %rbx value

ret # Now caller gets original %rbx backWhen You Need to Do This

Situation 1: You Need Extra Registers

my_function:

# You need more registers than caller-saved ones provide

push %rbx # Save callee-saved register

push %r12 # Save another callee-saved register

mov $100, %rbx # Use %rbx

mov $200, %r12 # Use %r12

# ... complex calculations ...

pop %r12 # Restore in reverse order

pop %rbx

retSituation 2: Long Function with Many Operations

complex_calculation:

push %rbx # Save before using

push %r12

push %r13

# Phase 1: Use %rbx

mov %rdi, %rbx

add $10, %rbx

# Phase 2: Use %r12

mov %rsi, %r12

mul %r12

# Phase 3: Use %r13

mov %rdx, %r13

add %r13, %rax

# Restore all registers

pop %r13

pop %r12

pop %rbx

retSituation 3: Function Calls Other Functions

wrapper_function:

push %rbx # Save before calling other functions

mov $100, %rbx # Use %rbx

call some_function # This might use %rbx too!

add %rbx, %rax # Still need %rbx after call

pop %rbx # Restore before returning

retStack Layout During Preservation

Before push %rbx:

┌─────────────┐

│ Return Addr │ ← %rsp

└─────────────┘

After push %rbx:

┌─────────────┐

│ Saved %rbx │ ← %rsp (new top)

├─────────────┤

│ Return Addr │

└─────────────┘

After push %r12:

┌─────────────┐

│ Saved %r12 │ ← %rsp (new top)

├─────────────┤

│ Saved %rbx │

├─────────────┤

│ Return Addr │

└─────────────┘

Complete Example

# Caller function

caller:

mov $100, %rbx # Caller sets %rbx = 100

mov $200, %r12 # Caller sets %r12 = 200

call callee # Call callee function

# After call, %rbx and %r12 should still be 100 and 200

add %rbx, %rax # Should add 100

ret

# Callee function

callee:

# Save callee-saved registers we want to use

push %rbx # Save caller's %rbx

push %r12 # Save caller's %r12

# Now we can use them freely

mov $500, %rbx # Use %rbx for our work

mov $600, %r12 # Use %r12 for our work

add %rbx, %r12 # %r12 = 500 + 600 = 1100

mov %r12, %rax # Return 1100

# Restore original values before returning

pop %r12 # Restore caller's %r12 = 200

pop %rbx # Restore caller's %rbx = 100

retKey Points

- Push before use: Save callee-saved registers before modifying them

- Pop before return: Restore them before returning

- Reverse order: Pop in reverse order of push (LIFO - Last In, First Out)

- Only if needed: Only save registers you actually use

- Caller-saved are free: You can use caller-saved registers without saving

Memory Trick:

- Push = “Put away for safekeeping”

- Pop = “Get back what you put away”

- Order: Like stacking plates - last plate on top comes off first

This ensures that function calls are “transparent” - the caller doesn’t know or care what registers the callee used internally!

Computer Architecture Terms Explained

Computer Architecture

Computer Architecture is the high-level design of a computer system. It defines:

- What operations the computer can perform

- How programs interact with the hardware

- The interface between software and hardware

- The overall system organization

Think of it as: The “blueprint” or “specification” of how a computer should work.

Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)

ISA is the interface between software and hardware. It defines:

- What instructions the processor can execute

- How instructions are encoded (binary format)

- What registers are available

- How memory is addressed

- What data types are supported

- How exceptions/interrupts are handled

ISA Examples:

- x86-64: Intel/AMD 64-bit processors

- ARM: ARM processors (phones, tablets, some servers)

- RISC-V: Open-source instruction set

- MIPS: Educational/embedded processors

ISA Components:

# x86-64 ISA examples

mov %rax, %rbx # Move instruction

add %rax, %rbx # Add instruction

jmp label # Jump instruction

call function # Call instruction

syscall # System call instructionMicroarchitecture

Microarchitecture is the low-level implementation of an ISA. It defines:

- How instructions are executed internally

- What execution units exist (ALU, FPU, etc.)

- How the pipeline works

- Cache organization

- Branch prediction mechanisms

- Out-of-order execution details

Think of it as: The “engineering details” of how the ISA is actually built.

Relationship Between Them

Software Program

↓

ISA Interface ← What the program sees

↓

Microarchitecture ← How it's actually implemented

↓

Hardware

Analogy: Car Design

- Architecture: “This car should have 4 wheels, an engine, and seats”

- ISA: “The steering wheel turns left/right, gas pedal accelerates, brake pedal stops”

- Microarchitecture: “The engine uses V8 configuration, fuel injection system, automatic transmission with 6 gears”

Examples

Same ISA, Different Microarchitectures:

x86-64 ISA can be implemented by different microarchitectures:

| Processor | Microarchitecture | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Intel Core i7 | Skylake/Coffee Lake | 4-8 cores, AVX-512, branch prediction |

| AMD Ryzen | Zen/Zen2/Zen3 | Different cache design, execution units |

| Intel Atom | Silvermont | Low-power, simpler pipeline |

All run the same x86-64 programs, but with different performance characteristics.

Different ISAs, Similar Goals:

| ISA | Microarchitecture | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ARM | Cortex-A78 | Mobile phones |

| x86-64 | Intel Core | Desktop/laptop |

| RISC-V | SiFive U74 | Embedded systems |

Levels of Abstraction

High Level

↓

┌─────────────────┐

│ Application │ ← Your C/Python program

├─────────────────┤

│ Operating │ ← Linux/Windows

│ System │

├─────────────────┤

│ ISA │ ← x86-64 instructions

├─────────────────┤

│ Microarchitecture│ ← How x86-64 is implemented

├─────────────────┤

│ Hardware │ ← Actual transistors

└─────────────────┘

Low Level

Why This Matters for Assembly

ISA Level (What You Write):

mov %rax, %rbx # This is ISA - same on all x86-64

add %rax, %rbx # This is ISA - same on all x86-64Microarchitecture Level (What Happens Inside):

- Intel processor: Might execute this in 1 cycle with 3 execution units

- AMD processor: Might execute this in 1 cycle with 2 execution units

- Different cache behavior: Intel might have better branch prediction

- Different power consumption: AMD might be more power-efficient

Key Takeaways

- ISA: The “contract” between software and hardware

- Microarchitecture: The “implementation” of that contract

- Same ISA: Programs run on different processors

- Different Microarchitecture: Different performance, power, features

- Assembly programming: You work at the ISA level

- Performance optimization: Understanding microarchitecture helps

For Assembly Learning:

- Focus on ISA (instruction set) - this is what you write

- Understand microarchitecture concepts (pipeline, cache) for optimization

- Know that your assembly code will run on any x86-64 processor, but performance varies

Think of ISA as the “language” and microarchitecture as the “accent” - same language, different ways of speaking it!

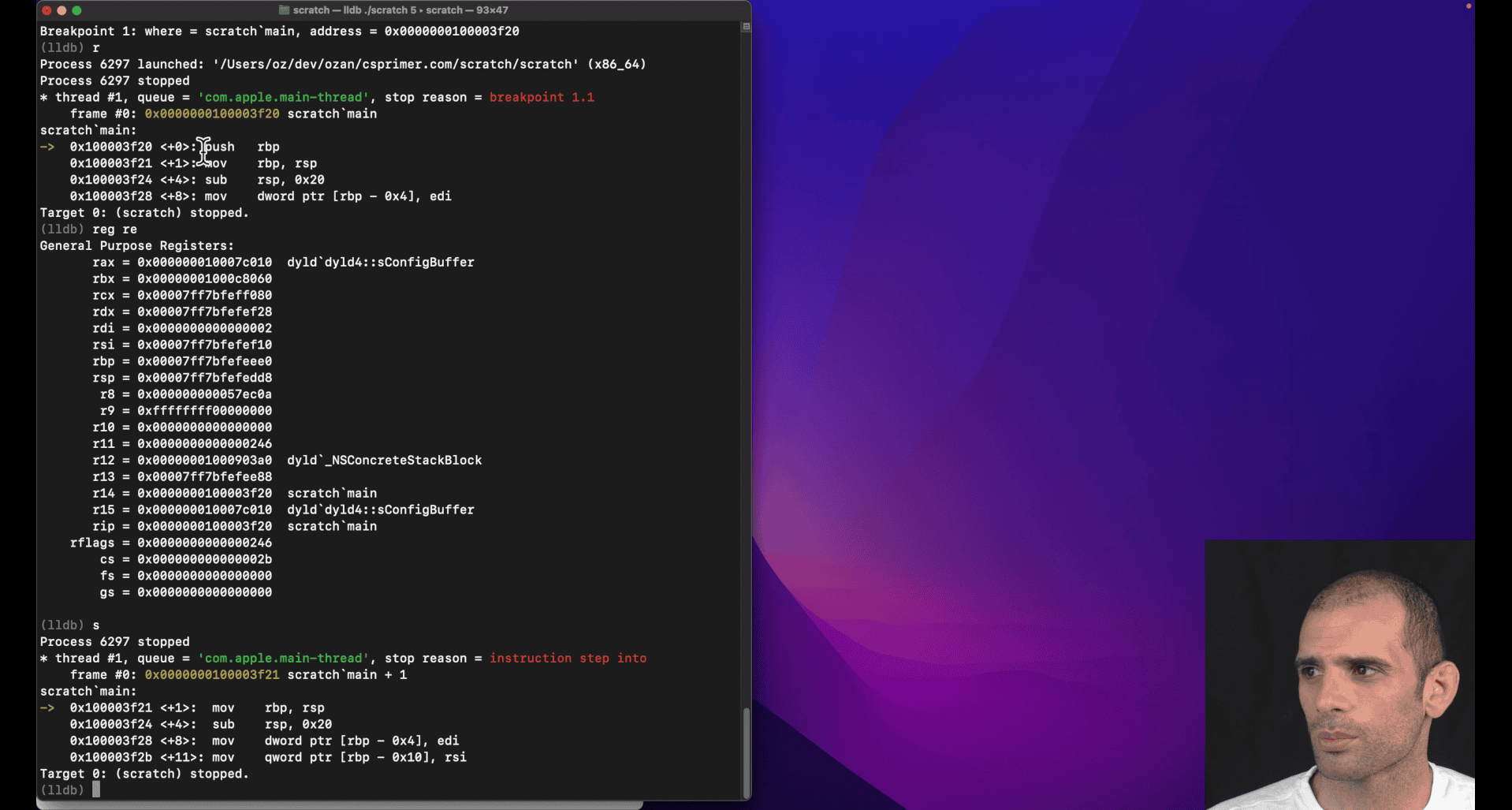

Sum to N

; Slower way:

mov eax, 0 ; Load immediate value 0 into eax

; Faster way:

xor eax, eax ; eax = eax ⊕ eax = 0anguage

XOR Bit-Level Visual Examples

XOR Truth Table

A | B | A ⊕ B

--|---|------

0 | 0 | 0

0 | 1 | 1

1 | 0 | 1

1 | 1 | 0

Key Rule: XOR returns 1 only when the inputs are different

Before XOR:

eax = 10110101

eax = 10110101

--------

XOR = 00000000 ← Always 0 when both operands are identical!

section .text

global sum_to_n

sum_to_n:

; accumlator , zero eax (return vale) "total"

; loop:

; ; add edi into eax, primer trying to use n-1 ,n-2 so that he can use rdi

; eventual will get to 0

; jump to loop if edi eq -1

; mov rax,0 ; if we use other reg, then we gonna copy that in the end, so just directly using rax

; faster to just xor to zero out than move rax,0

xor eax,eax

mov ecx,-1 ;;make this as cmp vaule

_loop:

add eax,edi ; intel way

sub edi,1

cmp edi,ecx

jne _loop

; sub 1 from edi

; comparing edi to -1 (break point?)

; jump to loop if edi != -1

ret

stage 1 this work

Your teacher is explaining a fundamental connection between arithmetic operations and conditional logic in assembly! Let me break down what they mean:

The Key Insight: SUB Modifies Flags for Jumps

Your teacher is pointing out that sub doesn’t just perform subtraction - it also updates CPU flags that conditional jump instructions examine to make decisions.

CPU Flags That SUB Modifies

When you execute sub eax, ebx, the CPU sets these flags based on the result:

Flags Modified by SUB:

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Zero Flag (ZF) - Set if result = 0 │

│ Carry Flag (CF) - Set if borrow occurred │

│ Sign Flag (SF) - Set if result < 0 │

│ Overflow Flag (OF) - Set if signed overflow │

│ Parity Flag (PF) - Set if even 1s │

│ Auxiliary Flag (AF)- Set if carry in low 4 bits │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

How Jumps Use These Flags

Conditional jumps examine these flags to decide whether to jump:

; Example: Compare two numbers

mov eax, 10

mov ebx, 5

sub eax, ebx ; eax = 5, flags updated based on (10-5=5)

; Now jumps can use the flags:

je equal ; Jump if ZF=1 (if eax was 0)

jne not_equal ; Jump if ZF=0 (if eax was not 0)

jl less ; Jump if SF≠OF (if result was negative)

jg greater ; Jump if ZF=0 AND SF=OF (if result was positive)Visual Example: SUB as Comparison

mov eax, 15

mov ebx, 10

sub eax, ebx ; eax = 5, but flags are set based on comparison

; Flags after SUB:

; ZF = 0 (result not zero)

; SF = 0 (result positive)

; CF = 0 (no borrow)

; OF = 0 (no overflow)

; Now we can jump based on these flags:

je equal ; Won't jump (ZF=0)

jne not_equal ; WILL jump (ZF=0)

jl less ; Won't jump (SF=OF=0)

jg greater ; WILL jump (ZF=0 and SF=OF=0)The Connection: CMP is Actually SUB!

Here’s the big revelation your teacher is hinting at:

; These two are essentially the same:

cmp eax, ebx ; Compare eax with ebx

sub eax, ebx ; Subtract ebx from eax

; The difference:

; CMP: Updates flags, doesn't store result

; SUB: Updates flags AND stores result in eaxPractical Example

mov eax, 20

mov ebx, 15

; Method 1: Using CMP (traditional)

cmp eax, ebx ; Compare without changing eax

jg greater ; Jump if eax > ebx

; eax still contains 20

; Method 2: Using SUB (what your teacher is pointing out)

sub eax, ebx ; eax = 5, flags set based on comparison

jg greater ; Jump if original eax > ebx

; eax now contains 5Why This Matters

Your teacher is teaching you that:

- Arithmetic operations affect program flow - SUB doesn’t just do math, it prepares flags for jumps

- CMP and SUB are related - CMP is SUB without storing the result

- Flags are the bridge between arithmetic and conditional logic

- You can use SUB for comparison if you don’t mind losing the original value

This is why understanding flags is crucial in assembly - they’re the mechanism that connects arithmetic operations to conditional program flow!

The Key Insight: SUB Sets Flags Automatically!

When sub edi,1 executes, it automatically sets CPU flags based on the result:

After sub edi,1:

- If edi was 5 → edi becomes 4 → flags indicate "positive"

- If edi was 1 → edi becomes 0 → flags indicate "zero"

- If edi was 0 → edi becomes -1 → flags indicate "negative"

How JG Uses These Flags

jg (Jump if Greater) examines the flags set by sub:

sub edi,1 ; edi = edi - 1, flags updated

jg _loop ; Jump if result > -1 (i.e., if edi >= 0)Step-by-Step Logic

Let’s trace through what happens:

Initial: edi = 3

Loop 1: sub edi,1 → edi = 2 → flags: positive → jg jumps → continue

Loop 2: sub edi,1 → edi = 1 → flags: positive → jg jumps → continue

Loop 3: sub edi,1 → edi = 0 → flags: zero → jg jumps → continue

Loop 4: sub edi,1 → edi = -1 → flags: negative → jg doesn't jump → exit

- this is a do while loop

much easy to remember damn

much easy to remember damn

middle → n/2 → 3 (i) → (i) +(i+1) ⇒3+4 (just my thinking)

n(n+1)/2 (n = total number )

mov ecx,edi

add edi,1 ;(n+1)

; mol edi, ecx this wont work these reg

imul edi,ecx

shr edi,1 ;;shift bit right , like /2

mov eax,edi

ret

---

mov ecx, edi ; ecx = n

inc edi ; edi = n + 1

mov eax, ecx ; eax = n

mul edi ; EDX:EAX = eax * edi = n * (n+1)

; Now divide by 2:

; If you know the product fits in 32 bits, and you only care about low 32 bits:

shr eax, 1 ; eax = (n*(n+1)) / 2

can’t use mul in here, use imul

mov eax,edi

inc edi

imul eax,edi

shr eax,1

retlldb debuging is easier in this case

b main, s in, check reg

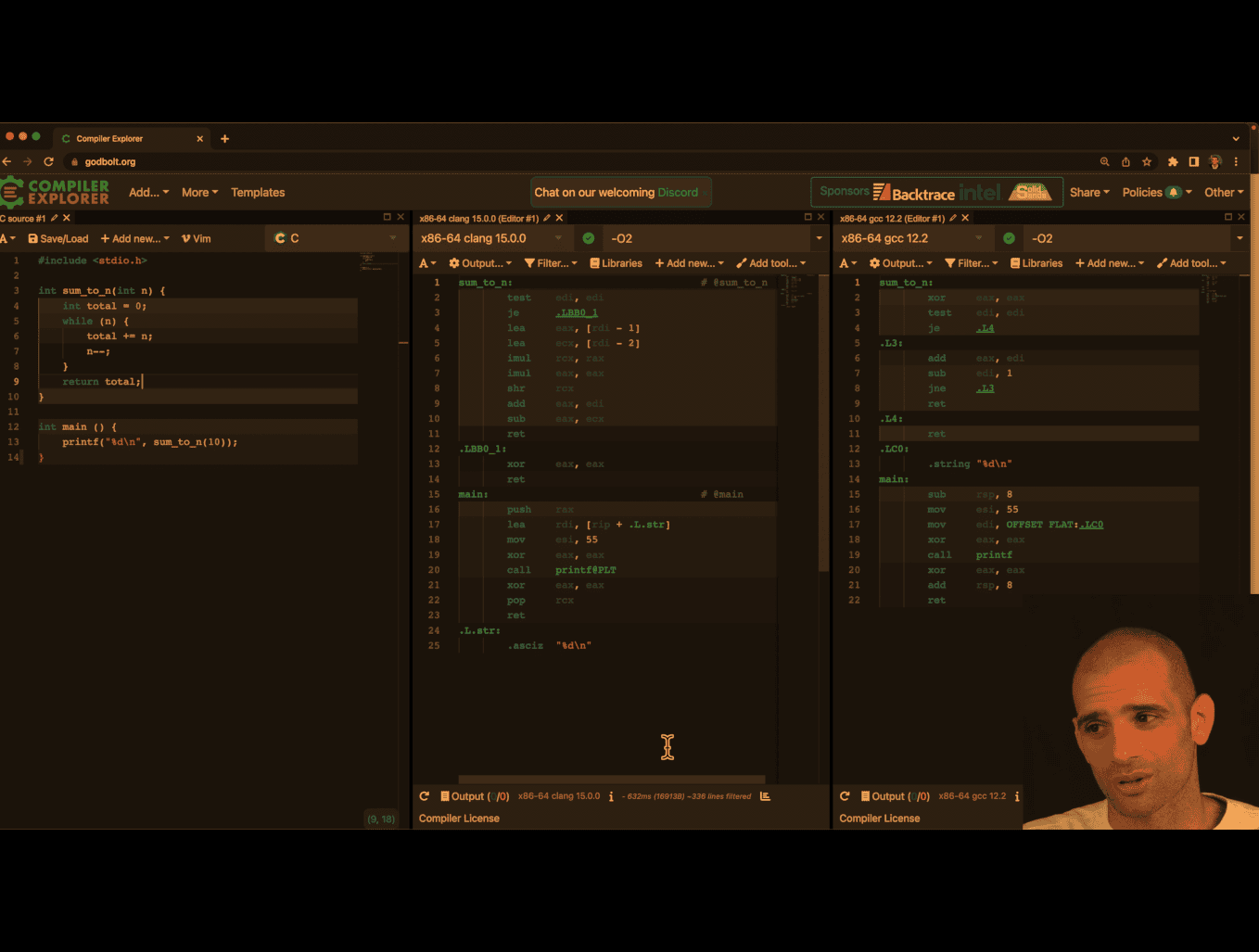

- interesting diff btw clang and gcc gcc here in terms of assembly of code

- clang win because it turns while loop case into constant case, the formula, damn

matrix-access

Explain the picture

Your teacher is showing two equivalent ways to compute the memory address of an element in a row‑major int matrix:

-

Top line (byte arithmetic):

- matrix + rindex _ (cols _ 4) + cindex * 4

- Meaning: start at base address

matrix, skiprindexfull rows (each row hascolsints, each int is 4 bytes), then movecindexmore ints (4 bytes each).

-

Bottom line (factored):

- matrix + 4 _ (rindex _ cols + cindex)

- Same thing, just factoring out the 4. The term in parentheses is the element offset; multiplying by 4 converts elements → bytes.

Key points:

- 4 is

sizeof(int)on your platform. More generally: matrix + sizeof(T) _ (rindex _ cols + cindex). - If you do pointer arithmetic on an

int*, you normally write(int*)matrix + (rindex * cols + cindex)because+ 1already advances by 4 bytes forint. - The inner offset

rindex * cols + cindexis the standard row‑major index.

section .text

global index

index:

; extern int index(int *matrix, int rows, int cols, int rindex, int cindex);

; rdi: matrix

; esi: rows

; edx: cols

; ecx: rindex

; r8d: cindex

imul ecx, edx

add ecx,r8d

imul ecx, 4

add rcx, rdi

mov eax,[rcx] ; this deference

ret

section .text

global index

index:

; extern int index(int *matrix, int rows, int cols, int rindex, int cindex);

; rdi: matrix

; esi: rows

; edx: cols

; ecx: rindex

; r8d: cindex

imul ecx, edx

add ecx,r8d

mov eax,[rdi + 4 * rcx]

ret

just deference inside pointer, damn

x8664 pangram

What that line does

- The expression

c & 0x1fkeeps only the low 5 bits ofc(values 0–31). - For ASCII letters this maps both cases to 1–26:

- ‘A’(65) → 65 & 31 = 1 … ‘Z’(90) → 26

- ‘a’(97) → 97 & 31 = 1 … ‘z’(122) → 26

1 << kbuilds a mask with bit k set.bs |= ...sets that bit inbsand keeps previous bits set.

So each letter toggles its corresponding bit 1..26 in bs.

Bit visual

Assume a 32‑bit view (bit 31 on the left … bit 0 on the right). MASK = 0x07fffffe has bits 1..26 set:

0000 0111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1110

^....................^

bit26 ............. bit1

Start with bs = 0.

- Seeing ‘C’ (ASCII 67):

- k = 67 & 31 = 3

- mask = 1 << 3 = 0b…00001000

- bs |= mask sets bit 3:

bs before: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

mask : 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000

bs after : 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000

- Seeing ‘x’ (ASCII 120):

- k = 120 & 31 = 24

- mask = 1 << 24 = 0b…0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

- bs after sets bit 24 as well:

bs before: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000

mask : 0000 0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

bs after : 0000 0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000

After processing the whole string, the pangram test

(bs & 0x07fffffe) == 0x07fffffe

checks that all bits 1..26 are set, meaning every letter A–Z/a–z appeared at least once.

Notes:

- The

if (c < '@') continue;quickly skips many non-letters; letters below ’@’ don’t exist, and letters map to 1..26 anyway. - Using

1u << ...is slightly safer (unsigned shift), but with shifts up to 26 a plain1is fine on typical 32‑bit ints.

x64 pangram

#define MASK 0x07fffffe

bool ispangram(char *s) {

uint32_t bs = 0;

char c;

while ((c = *s++) != '\0') {

if (c < '@')

continue; // ignore first 64 chars in ascii table

bs |= 1 << (c & 0x1f);

}

return (bs & MASK) == MASK;

}%define MASK 0x07fffffe

section .text

global pangram

pangram:

; rdi: source string

xor ecx,ecx ; bs = 0

.loop:

movzx edx, byte [rdi] ; c=*s will be edx, read from rdi, zero out extend

cmp edx,0

je .end

add rdi,1 ; s++

cmp edx,'@' ; if c is in first 64 chars of ascii table

jl .loop ; continue

and edx,0x1f

bts ecx, edx ;bitset set ecx to how many bits of edx

jmp .loop

.end:

xor eax,eax

and ecx,MASK ; last return part

cmp ecx,MASK

sete al ; set equal

; todo sometime return 1!

retbinary-converter asm

#include <assert.h>

#include <stdio.h>

extern int binary_convert(char *bits);

int main(void) {

assert(binary_convert("0") == 0);

assert(binary_convert("1") == 1);

assert(binary_convert("110") == 6);

assert(binary_convert("1111") == 15);

assert(binary_convert("10101101") == 173);

printf("OK\n");

}section .text

global binary_convert

binary_convert:

xor eax,eax

.loop:

movzx ecx,byte[rdi]

cmp ecx,0

je .end

shl eax,1

and ecx, 1 ; TODO this assumes that , ecx is surly '0' o '1'

add eax,ecx

add rdi,1

jmp .loop

.end:

ret

x86-64 Assembly Logic: binary_convert

This explains what your teacher is teaching in the provided routine: converting a binary string like “10101101” into an integer using shifts and adds.

High-level algorithm (language-agnostic)

Given a string of bits b0 b1 … bn-1 (each ‘0’ or ‘1’), compute the integer value:

- Start with result = 0

- For each character c in the string:

- result = result << 1 // multiply by 2

- result = result + bit(c) // add 0 or 1

- Return result

This is exactly how we interpret binary: left shift accumulates previous bits, then we add the new least-significant bit.

System V AMD64 calling convention refresher

- First argument (char* s) is in

rdi - Return value is in

rax eaxis the low 32 bits ofrax- Clobbering caller-saved registers like

rax,rcx,rdiis allowed in leaf functions unless the ABI requires otherwise for the caller

The code

section .text

global binary_convert

binary_convert:

xor eax,eax

.loop:

movzx ecx,byte[rdi]

cmp ecx,0

je .end

shl eax,1

and ecx, 1 ; TODO this assumes that , ecx is surly '0' o '1'

add eax,ecx

add rdi,1

jmp .loop

.end:

retLine-by-line explanation

xor eax, eax- Sets

eax = 0(the current accumulated integer).xor reg,regis a common zeroing idiom.

- Sets

.loop:labelmovzx ecx, byte [rdi]- Load the next byte from the string pointer

rdiintoecxand zero-extend it. After this,ecxholds the ASCII code of the current character.

- Load the next byte from the string pointer

cmp ecx, 0thenje .end- Checks for the string terminator

\0. If end of string, jump to return.

- Checks for the string terminator

shl eax, 1- Multiply current result by 2 (shift left by 1). This is how we make room for the next bit.

and ecx, 1- Mask the low bit of the ASCII code. This is a clever fast-path that works because ASCII ‘0’ (0x30 = 48) is even (low bit 0) and ‘1’ (0x31 = 49) is odd (low bit 1). It is unsafe for other characters; it treats any odd ASCII as 1 and any even ASCII as 0.

add eax, ecx- Add that bit (0 or 1) to the result.

add rdi, 1- Advance the pointer to the next character.

jmp .loop- Repeat.

.end: ret- Return with the result in

eax/rax.

- Return with the result in

Worked trace: input “10101101”

We track only eax (result) and the current char.

Initial: eax = 0

- c=‘1’ (0x31 → low bit 1)

- shift: eax = 0 << 1 = 0

- add: eax = 0 + 1 = 1

- c=‘0’ (0x30 → low bit 0)

- shift: 1 << 1 = 2

- add: 2 + 0 = 2

- c=‘1’

- shift: 2 << 1 = 4

- add: 4 + 1 = 5

- c=‘0’

- shift: 5 << 1 = 10

- add: 10 + 0 = 10

- c=‘1’

- shift: 10 << 1 = 20

- add: 20 + 1 = 21

- c=‘1’

- shift: 21 << 1 = 42

- add: 42 + 1 = 43

- c=‘0’

- shift: 43 << 1 = 86

- add: 86 + 0 = 86

- c=‘1’

- shift: 86 << 1 = 172

- add: 172 + 1 = 173

End: ‘\0’ → return 173. Matches your test.

Visual bit growth (LSB on the right)

After each char: value in binary

- start: 00000000

- ‘1’ → 00000001

- ‘0’ → (<<1): 00000010

- ‘1’ → 00000101

- ‘0’ → 00001010

- ‘1’ → 00010101

- ‘1’ → 00101011

- ‘0’ → 01010110

- ‘1’ → 10101101 (173)

What your teacher is emphasizing

- Binary parsing is just repeated: result = result * 2 + next_bit

- Using

shlto multiply by 2 andand 1to extract a bit - Looping over a C string via pointer in

rdiand checking for\0 - Returning via

eaxper ABI

Pitfalls and correctness

- The

and ecx, 1trick accepts any odd byte as bit 1 and any even byte as bit 0. That means characters like ‘3’ (0x33) would be treated as 1, and ‘2’ (0x32) as 0. If the input may contain non-‘0’/‘1’, you should validate.

Safer variant (validate ASCII ‘0’/‘1’)

Conceptually:

- If c == ‘0’ → bit = 0

- Else if c == ‘1’ → bit = 1

- Else stop or error

One assembly approach (keeping branchless where possible):

- Subtract ‘0’ to normalize:

ecx = c - '0'→ ‘0’→0, ‘1’→1, others outside 0..1 - Test range 0..1; if not in range, decide policy (stop or reject)

Sketch:

; ecx currently holds c (zero-extended)

sub ecx, '0' ; '0'->0, '1'->1, others → not 0/1

cmp ecx, 1

ja .invalid ; if ecx > 1, it's invalid char

; here ecx is 0 or 1, safe to use

shl eax, 1

add eax, ecx

; advance pointer and loopPolicy at .invalid could be to stop parsing (like strtol) or return an error code.

Why 32-bit eax is fine

- Your test values fit in 32 bits, and zeroing

eaximplicitly zeros the fullrax. If you want to allow inputs longer than 31 bits, you can perform the shift/add inraxwithshl rax,1andadd rax,rcx(ensurercxis 0/1 and properly zero-extended).

C equivalent for intuition

##include <stdint.h>

int binary_convert(const char *s) {

uint32_t x = 0;

for (unsigned char c; (c = *s++) != '\0'; ) {

x <<= 1;

x += (c & 1); // same assumption as asm: even→0, odd→1

}

return (int)x;

}Takeaways

- Parsing binary is shift-left then add-bit

and 1extracts the low bit fast, but assumes valid input- Understanding the ABI and pointer walking is key to reading small assembly routines

-

Pointer Dereferencing:

- The register

rdiholds the memory address of the current character in the string. byte [rdi]means: “Access the byte at the memory address stored inrdi.”

- The register

-

Zero-Extension:

movzxstands for “move with zero-extension.”- It loads the byte (8 bits) from

byte [rdi]into the lower 8 bits ofecxand sets the upper 24 bits ofecxto 0. This ensures thatecxholds a 32-bit value with the loaded byte in the least significant byte (LSB).

Memory Layout (String in Memory)

Let’s say the string is "10101101\0" (null-terminated). The memory layout might look like this:

Address (rdi) | Value (Byte) | ASCII Code |

|---|---|---|

0x1000 | '1' | 0x31 |

0x1001 | '0' | 0x30 |

0x1002 | '1' | 0x31 |

0x1003 | '0' | 0x30 |

0x1004 | '1' | 0x31 |

0x1005 | '1' | 0x31 |

0x1006 | '0' | 0x30 |

0x1007 | '1' | 0x31 |

0x1008 | '\0' | 0x00 |

Execution Steps

-

First Iteration:

rdi = 0x1000movzx ecx, byte [rdi]→ Load'1'(ASCII0x31) intoecx.ecx = 0x00000031(32-bit value with zero-extension).

-

Second Iteration:

add rdi, 1→rdi = 0x1001movzx ecx, byte [rdi]→ Load'0'(ASCII0x30) intoecx.ecx = 0x00000030.

-

Third Iteration:

add rdi, 1→rdi = 0x1002movzx ecx, byte [rdi]→ Load'1'(ASCII0x31) intoecx.ecx = 0x00000031.

-

Repeat Until Null Terminator:

- The loop continues until

cmp ecx, 0detects the null terminator (0x00) atrdi = 0x1008.

- The loop continues until

cone-volumn

mulss and xmm0 are part of the x86 assembly language, specifically for the SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) instruction set.

-

mulss: This instruction performs scalar single-precision floating-point multiplication. It multiplies the lower 32-bit floating-point value in the source operand (register or memory) with the lower 32-bit floating-point value in the destination operand (register) and stores the result in the destination operand. The higher bits of the destination register remain unchanged. -

xmm0: This is one of the 128-bit SSE registers. It is used to store floating-point values or SIMD data. In the context ofmulss, only the lower 32 bits ofxmm0are used for the operation.

In your code:

mulss xmm0, xmm0This multiplies the lower 32-bit floating-point value in xmm0 by itself (i.e., xmm0 = xmm0 * xmm0), effectively squaring the value.

-

SSE Registers (

xmm0–xmm15):- These are 128-bit registers introduced with the SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) instruction set.

- They can handle scalar (single value) or SIMD (multiple values) floating-point operations.

- Instructions like

mulss(scalar single-precision) andmulps(packed single-precision) use these registers.

-

x87 FPU Stack Registers (

st(0)–st(7)):- These are part of the older x87 floating-point unit, which uses a stack-based architecture.

- Instructions like

fmuloperate on these registers. - They support extended precision (80-bit floating-point numbers).

Modern Usage

- SSE/AVX registers (

xmm,ymm,zmm) are preferred in modern code because they are faster and support SIMD operations. - The x87 FPU is mostly used for legacy code or when extended precision is required.

In your code, xmm0 is used because it is part of the SSE register set, which is optimized for single-precision floating-point operations.

mulss Example:

movss xmm0, [a] ; Load scalar value from memory into xmm0

movss xmm1, [b] ; Load scalar value from memory into xmm1

mulss xmm0, xmm1 ; xmm0 = xmm0 * xmm1 (only lower 32 bits are multiplied)Here, only the lower 32 bits of xmm0 and xmm1 are multiplied, and the result is stored in the lower 32 bits of xmm0.

mulps Example:

movaps xmm0, [vec1] ; Load packed values (4 floats) from memory into xmm0

movaps xmm1, [vec2] ; Load packed values (4 floats) from memory into xmm1

mulps xmm0, xmm1 ; xmm0 = xmm0 * xmm1 (element-wise multiplication of 4 floats)Here, all four 32-bit floating-point values in xmm0 and xmm1 are multiplied in parallel, and the results are stored in xmm0.

Memory Layout Example:

Assume the memory contains:

vec1: dd 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 ; Four floats

vec2: dd 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0 ; Four floatsAfter mulps xmm0, xmm1, the result in xmm0 will be:

xmm0 = [1.0*5.0, 2.0*6.0, 3.0*7.0, 4.0*8.0]

= [5.0, 12.0, 21.0, 32.0]

Summary

- Use

mulssfor single-value (scalar) floating-point multiplication. - Use

mulpsfor parallel (SIMD) multiplication of multiple floating-point values.

#include <assert.h>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define float_near(a, b) fabsf((a) - (b)) < 0.01

extern float volume(float radius, float height);

int main(void) {

assert(float_near(0.0f, volume(0.0f, 0.0f)));

assert(float_near(2.09f, volume(1.0f, 2.0f)));

assert(float_near(174.23f, volume(5.5f, 5.5f)));

assert(float_near(9.05f, volume(1.234f, 5.678f)));

printf("OK\n");

}default rel

section .text

global volume

volume:

;V = r *r *h *pi /3

mulss xmm0,xmm0 ; v =r*r

mulss xmm0,xmm1 ; V *= h

mulss xmm0, [pi_on_3] ; V*= pi/3

ret

section .rodata ;constant data ? slight protection

;pi_on_3: dd 3.14 ; floating point 3.14

pi_on_3: dd 1.0471975512 ; floating point 3.14

low level recursion

goal : what is function call in the low level, what is stack for

In assembly language, push and pop are instructions for manipulating the stack:

-

push: Puts a value onto the stack by:- Decrementing the stack pointer (RSP)

- Storing the value at the new stack pointer location

-

pop: Retrieves a value from the stack by:- Loading the value at the current stack pointer location

- Incrementing the stack pointer

In this Fibonacci implementation, the stack is needed for two key reasons:

-

Preserving values during function calls When

fibcalls itself recursively, registers get overwritten. For example:- Line 12:

push rdisavesn-1before the recursive call - Line 17:

push raxsaves the result offib(n-1)before calculatingfib(n-2)

- Line 12:

-

Managing recursive call state Each recursive call needs its own context (parameters and return values)

Without the stack, the intermediate values would be lost when the function makes recursive calls, making it impossible to add fib(n-1) and fib(n-2) together at the end.

section .text

global fib

fib:

;general case:

;return fib(n-1)+fib(n-2)

;

mov eax,edi ; edi -> n , eax -> return ; base case: if n <= 1, return n

cmp edi,1

jle .end

sub edi, 1

push rdi ; push n -1 the top the stack is n-1, as edi will ebe clobbered

call fib ; f(n-1) need to use stack now, some value need to be modified by the callee

pop rdi

; we get result in eax

;

push rax ; push f(n-1) to stack,as eax will be clobbered

sub edi,1

call fib ; f(n-1)

pop rcx; eax has value at the moment, pop previously computed f(n-1) from top of stack and ...

add eax , ecx ; add it into newly computed f(n-2)

.end

ret

- stack alignment requirements

Your teacher is referring to stack alignment requirements in the x64 calling convention (System V ABI on Linux).

The key rule: The stack pointer (RSP) must be 16-byte aligned before each call instruction.

Here’s what’s happening in your code:

-

When your function starts: RSP is misaligned (8 bytes off from 16-byte boundary) because the

call fibinstruction pushed an 8-byte return address -

Your pushes/pops:

push rdi(line 12) - pushes 8 bytespush rax(line 17) - pushes 8 bytes- Total: 16 bytes pushed, so RSP becomes 16-byte aligned again

-

Before recursive calls: The stack is properly aligned when you call

fib

Why alignment matters:

- Modern processors and some instructions (especially SIMD) require 16-byte aligned memory access for optimal performance

- The ABI mandates it - violating alignment can cause crashes or performance penalties

- Some system functions expect proper alignment

In your code: You’re accidentally getting correct alignment because you push exactly 16 bytes total (2 × 8-byte pushes). But this is fragile - if you added another push without a matching one, you’d break alignment.

Proper practice: Explicitly ensure RSP is 16-byte aligned before each call, often by adjusting RSP or using sub rsp, 8 if needed.

Why Use EBP as a Frame Pointer?

- It gives constant offsets for parameters and locals throughout the function.

- Debuggers and backtracers can easily walk frames using saved EBP.

- Modern compilers may omit frame pointers for optimization, but the conceptual model remains.

Mapping to 64-bit System V (Linux/macOS)

Key differences vs 32-bit cdecl:

- First six integer/pointer parameters are in registers:

RDI,RSI,RDX,RCX,R8,R9(remaining go on stack). - Return value is in

RAX. - Callee-saved:

RBX,RBP,R12–R15. - 16-byte stack alignment requirement at each

call. On entry to a function (right after acall),RSP % 16 == 8. Before you execute anothercall, you must adjust the stack soRSP % 16 == 0(e.g.,pushonce orsub rsp, 8). - Leaf functions (no calls) may use the red zone (128 bytes below

RSP) without adjustingRSP.

Minimal 64-bit prologue/epilogue pattern:

; Prologue

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, N ; allocate locals (choose N to keep alignment before calls)

; ... body ...

; Epilogue

mov rsp, rbp

pop rbp

retWhy Push/Pop and How the Stack Changes

x86-64 push/pop semantics (32-bit similar with 4-byte steps):

push rX→rsp = rsp - 8; [rsp] = rXpop rX→rX = [rsp]; rsp = rsp + 8

LIFO discipline lets you save and restore temporary state (parameters, partial results, saved registers) and also helps meet alignment constraints before calls.

Checklist: Writing Correct Calls

-

Caller side:

- Save caller-saved registers you need later.

- Place arguments (stack or regs depending on ABI).

- Ensure stack alignment before

call(SysV64:rsp % 16 == 0). - Call target and then clean up arguments (cdecl) / not needed (SysV64’s callee cleans “home space” only on Windows x64, not SysV).

-

Callee side:

- Prologue: save

EBP/RBP, set frame, allocate locals, save callee-saved you touch. - Body: do work, keep contract.

- Epilogue: restore callee-saved, deallocate locals, restore frame, place return in

EAX/RAX,ret.

- Prologue: save

Key Takeaways

- The stack is the scratchpad for function calls: return addresses, parameters, locals, saved registers.

- Calling conventions are contracts that let separately compiled code interoperate.

- Visualizing offsets from

EBP/RBPmakes parameter/local access and frame layout clear. - On 64-bit SysV, remember the 16-byte alignment rule before each

call.

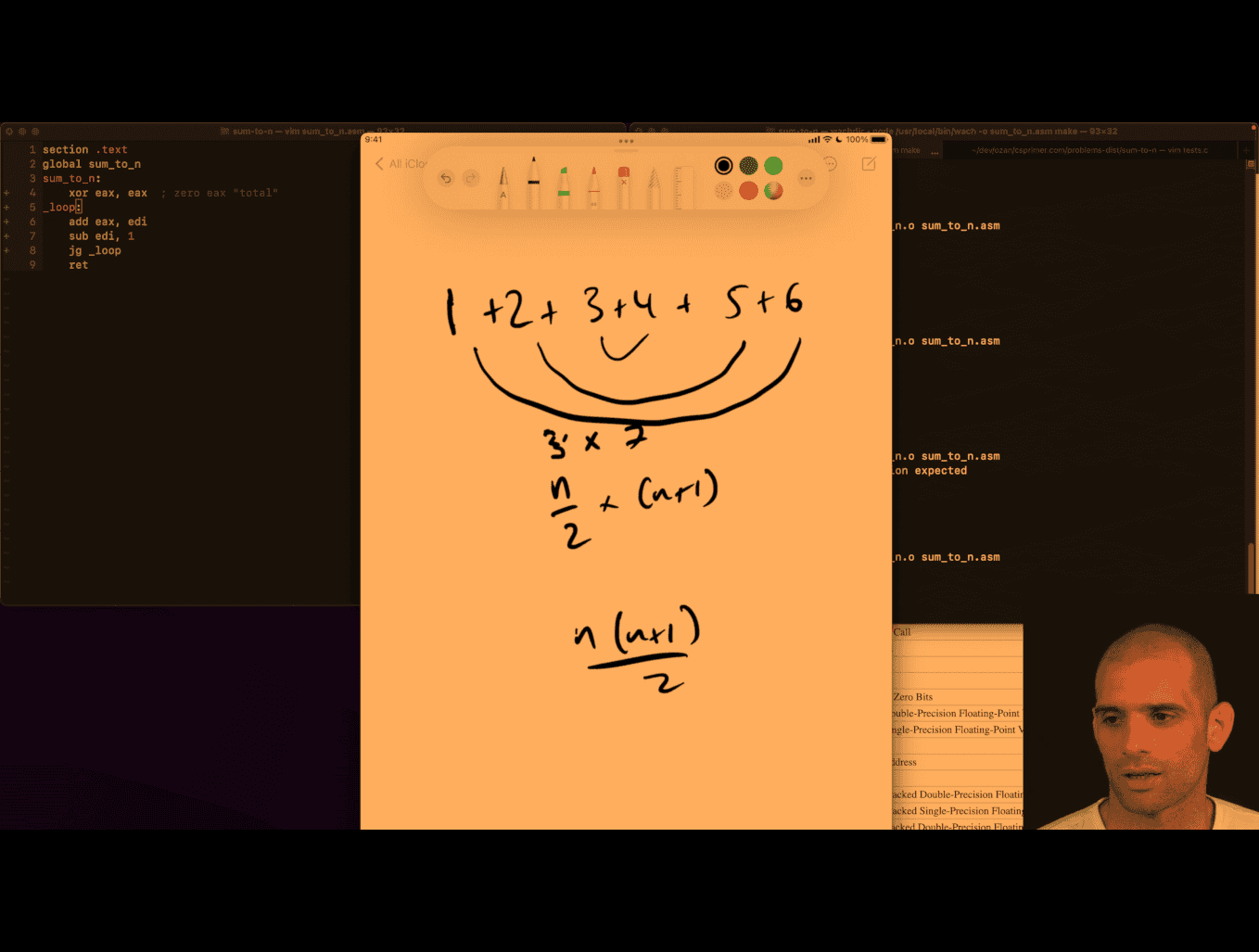

What is the fetch decode execute cycle

Faster sum

- google/benchmark: A microbenchmark support library perf as other tool as well

- Linux perf Examples yuninxia/hands-on-simd-programming: 🧩 Hands-on SIMD Programming with C++

look deep what is going on , and how to beat O1 in gcc

concept: use your pc architecture, e.g. skyleak intel, 8 thread if able to use c to tell the compiler that the code are independent, then it can run faster

SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) code is programming that uses special processor instructions to perform the same operation on multiple data points simultaneously, significantly boosting performance for tasks like image and audio processing. You can write SIMD code directly using compiler intrinsics (e.g., Intel’s SSE/AVX, ARM’s NEON), or rely on libraries (like NumPy or Numba for Python, or high-level libraries like simdjson for JSON parsing) and compilers that automatically “vectorize” your code to leverage these instructions.

/* int sum(int *nums, int n) { */

/* int total = 0; */

/* for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) */

/* total += nums[i]; */

/* return total; */

/* } */

int sum(int *nums, int n) {

int t1 = 0, t2 = 0, t3 = 0, t4 = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 4) {

t1 += nums[i];

t2 += nums[i + 1];

t3 += nums[i + 2];

t4 += nums[i + 3];

}

return t1 + t2 + t3 + t4;

}- tested on clang , cc (gcc) -O 2 , with manual t1..t4 , gcc -O2 better than clang

- however, og iterative movement, clang -O2 is the best of the best in the case, damn

I test it with t8 in gcc -O2 , close to clang -O2 non optimize, so clang i guess is also using similar approach

yuninxia/hands-on-simd-programming: 🧩 Hands-on SIMD Programming with C++

- clang compiler is able to found vectorized register, and using simd programming, that is specifically for your cpu bits

e.g

paddd xmm0 xmm2

Vector Registers Explained

%xmm0,%xmm1,%xmm2are 128-bit SIMD registers- Each can hold 4 x 32-bit integers or 2 x 64-bit integers simultaneously

- Operations work on all elements in parallel

Assembly Breakdown

at & t style , not intel

pxor %xmm1,%xmm1 # Clear xmm1 to zero (4 zeros)

movdqu (%rdi,%rsi,1),%xmm2 # Load 4 integers from memory into xmm2

paddd %xmm2,%xmm0 # Parallel add: xmm0 += xmm2 (4 additions at once)

movdqu 0x10(%rdi,%rsi,1),%xmm2 # Load next 4 integers (16 bytes offset)

paddd %xmm2,%xmm1 # Parallel add to second accumulatorHow Clang Optimizes sum += i

For a simple loop like:

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

sum += arr[i];

}Clang -O2 applies:

- Loop Unrolling: Process 8 elements per iteration instead of 1

- Vectorization: Use SIMD to add 4 integers simultaneously

- Multiple Accumulators: Two separate sum registers (

xmm0,xmm1) to avoid dependency chains - Memory Prefetching: Load next data while processing current

CPU Microarchitecture Fundamentals

1. Instruction Pipeline

Modern CPUs don’t execute instructions one at a time. Instead, they use a pipeline that processes multiple instructions simultaneously:

Clock Cycle: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Instruction 1: [F] [D] [E] [M] [W]

Instruction 2: [F] [D] [E] [M] [W]

Instruction 3: [F] [D] [E] [M] [W]

Instruction 4: [F] [D] [E] [M] [W]

F = Fetch, D = Decode, E = Execute, M = Memory, W = Write-back

Key Insight: If instructions are independent, the CPU can start executing the next instruction before the previous one finishes.

2. Out-of-Order Execution

Modern CPUs can reorder instructions to maximize parallelism:

// Original order:

a = x + y; // Instruction 1

b = z + w; // Instruction 2 (independent of instruction 1)

c = a + b; // Instruction 3 (depends on 1 and 2)

// CPU might execute as:

// Cycle 1: Start x+y and z+w simultaneously

// Cycle 2: Finish both additions

// Cycle 3: Start a+bCompiler Limitations

- Conservative Analysis: Compilers must be safe and can’t always prove independence

- Heuristic-Based: Optimization decisions are based on patterns, not perfect analysis

- Generic Optimizations: Compilers optimize for average cases, not your specific data

Human Advantages

- Domain Knowledge: You know your data patterns

- Aggressive Optimization: You can make assumptions compilers can’t

- Targeted Optimization: You can optimize for specific CPU characteristics

Performance Analysis with perf

Basic perf Commands

## Profile your program

perf record ./benchmark_O1

perf report

## Get detailed statistics

perf stat ./benchmark_O1

## Analyze cache performance

perf stat -e cache-misses,cache-references ./benchmark_O1

## Profile specific functions

perf record -g ./benchmark_O1

perf report --stdioKey Metrics to Watch

- Instructions Per Cycle (IPC): Higher is better

- Cache Miss Rate: Lower is better

- Branch Misprediction Rate: Lower is better

- Memory Bandwidth: Higher is better

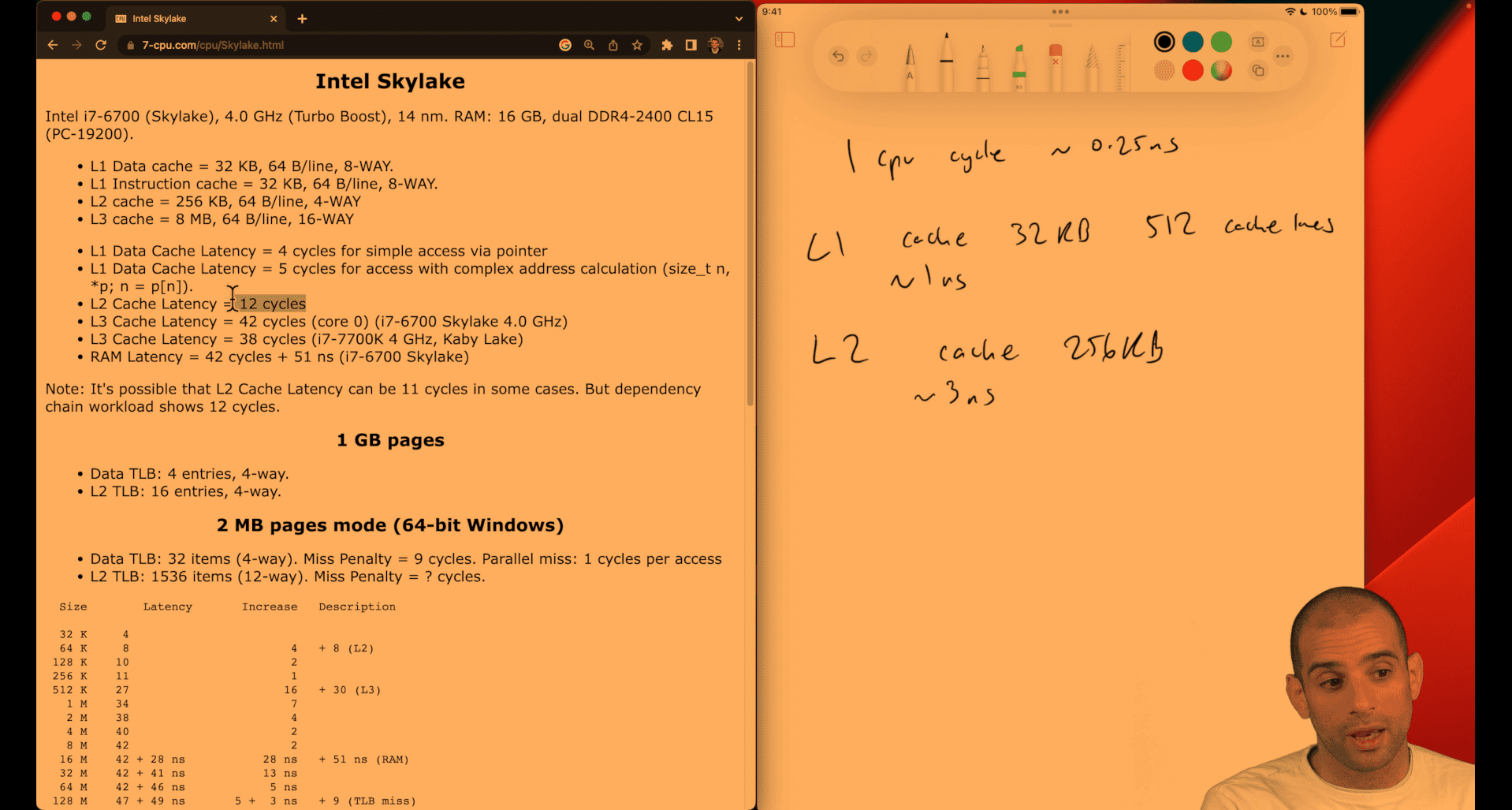

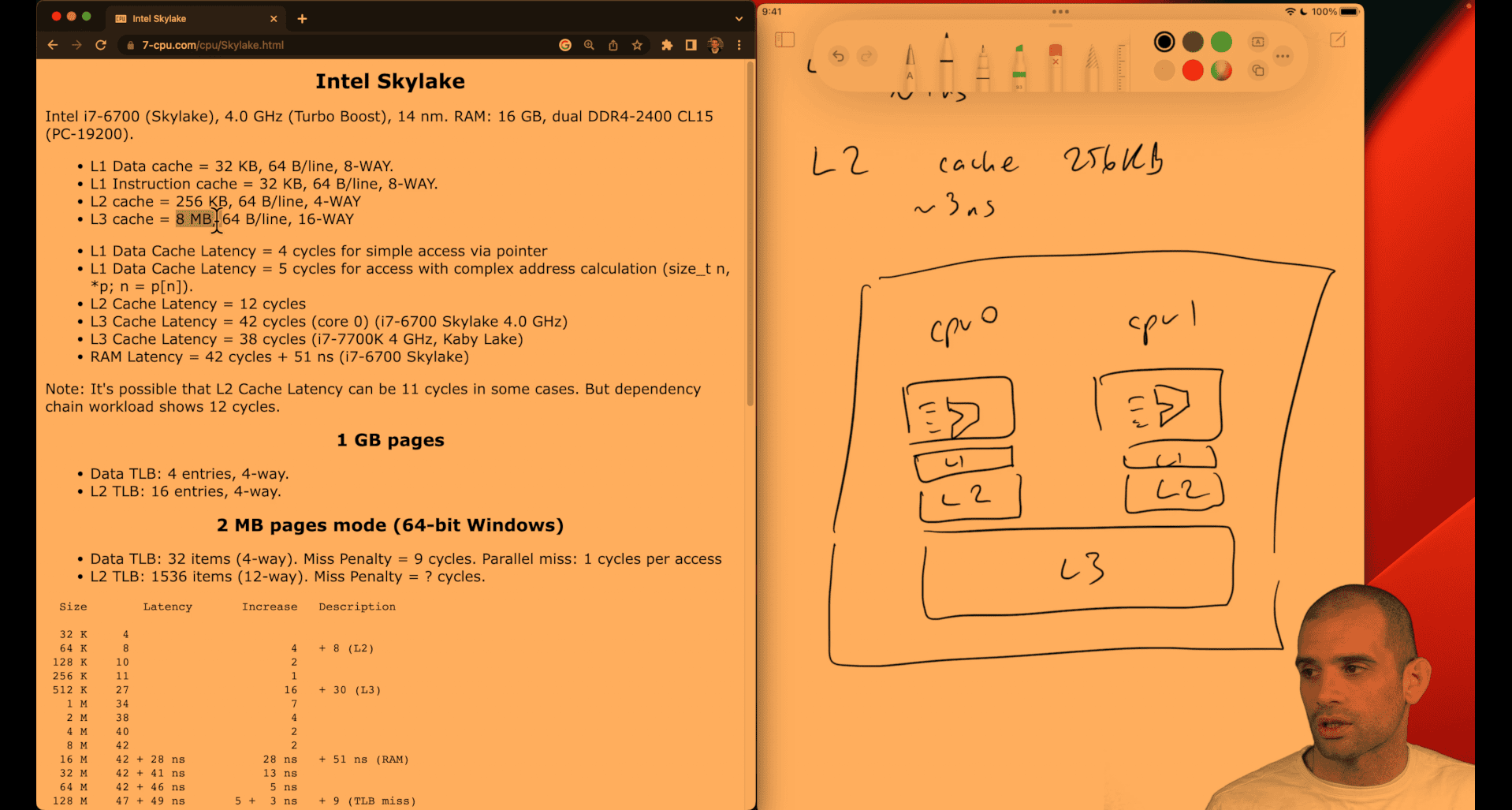

Understanding Your CPU: Intel Skylake

Skylake Characteristics

- 8 threads (4 cores with hyperthreading)

- Out-of-order execution with 8 execution ports

- AVX2 support for 256-bit SIMD operations

- L1 cache: 32KB data + 32KB instruction per core

- L2 cache: 256KB per core

- L3 cache: 8MB shared

Why Your Optimization Works

// Your 4-way unrolling exploits:

t1 += nums[i]; // Port 2/3: Load + Add

t2 += nums[i+1]; // Port 2/3: Load + Add (parallel)

t3 += nums[i+2]; // Port 2/3: Load + Add (parallel)

t4 += nums[i+3]; // Port 2/3: Load + Add (parallel)Skylake can execute 4 independent load+add operations simultaneously!

Advanced Optimization Techniques

1. SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data)

##include <immintrin.h>

int sum_simd(int *nums, int n) {

__m256i sum_vec = _mm256_setzero_si256();

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 8) {

__m256i data = _mm256_loadu_si256((__m256i*)&nums[i]);

sum_vec = _mm256_add_epi32(sum_vec, data);

}

// Horizontal sum

int result[8];

_mm256_storeu_si256((__m256i*)result, sum_vec);

return result[0] + result[1] + result[2] + result[3] +

result[4] + result[5] + result[6] + result[7];

}2. Cache-Aware Optimization

// Process data in cache-friendly chunks

int sum_cache_aware(int *nums, int n) {

const int CACHE_LINE_SIZE = 64;

const int INTS_PER_LINE = CACHE_LINE_SIZE / sizeof(int);

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += INTS_PER_LINE) {

int chunk_sum = 0;

for (int j = 0; j < INTS_PER_LINE && i + j < n; j++) {

chunk_sum += nums[i + j];

}

total += chunk_sum;

}

return total;

}3. Compiler Hints

// Tell compiler about data independence

int sum_hinted(int *nums, int n) {

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

total += nums[i];

__builtin_prefetch(&nums[i + 1], 0, 3); // Prefetch next element

}

return total;

}Key Takeaways

- CPU Parallelism: Modern CPUs can execute multiple independent instructions simultaneously

- Compiler Limitations: Compilers can’t always find the best optimizations

- Manual Optimization: Understanding CPU architecture lets you write faster code

- Measurement: Always benchmark your optimizations with real tools

- Targeted Optimization: Optimize for your specific CPU and data patterns

Next Steps

- Profile Your Code: Use

perfto find bottlenecks - Experiment: Try different unrolling factors and techniques

- Learn SIMD: Use vector instructions for maximum performance

- Cache Optimization: Understand memory hierarchy and access patterns

- Assembly Analysis: Look at generated assembly to understand compiler decisions

Remember: Premature optimization is the root of all evil, but understanding how to optimize when needed is invaluable!

Color quantizing

Got it 👍 Let’s keep it short and clear:

Color Quantizing

- What it is: Reducing the number of distinct colors in an image (e.g., from millions → 256 palette colors).

- Why: Saves memory, makes processing/rendering faster, and is common in GIFs, icons, or embedded systems.

- How: Each pixel’s RGB value is mapped to the “nearest” color in a limited palette (via clustering, uniform quantization, or lookup tables).

Branchless Color Conversion

-

Normal approach: Color conversion (say RGB → grayscale) often uses

ifconditions or clamps like:if (val < 0) val = 0; if (val > 255) val = 255;which cause branches → slower on modern CPUs due to pipeline stalls.

-

Branchless approach: Replace conditionals with arithmetic/bitwise tricks. Example (clamping to [0,255]):

val = (val & ~(val >> 31)); // clamp negatives to 0 val = (val | ((255 - val) >> 31)); // clamp above 255 to 255or using

min/maxintrinsics (_mm_min_epu8,_mm_max_epu8) in SIMD.

👉 Why branchless? Faster and more predictable performance, especially in inner loops of image processing.

#define RED0 0x00

#define RED1 0x20

#define RED2 0x40

#define RED3 0x60

#define RED4 0x80

#define RED5 0xa0

#define RED6 0xc0

#define RED7 0xe0

#define GREEN0 0x00

#define GREEN1 0x04

#define GREEN2 0x08

#define GREEN3 0x0c

#define GREEN4 0x10

#define GREEN5 0x14

#define GREEN6 0x18

#define GREEN7 0x1c

#define BLUE0 0x00

#define BLUE1 0x01

#define BLUE2 0x02

#define BLUE3 0x03

unsigned char quantize(unsigned char red, unsigned char green,

unsigned char blue) {

return (red & 0xe0) | ((green & 0xe0) >> 3) | (blue >> 6);

// 3-3-2 bit rgb

}

unsigned char quantize_prior(unsigned char red, unsigned char green,

unsigned char blue) {

unsigned char out = 0;

if (red < 0x20)

out += RED0;

else if (red < 0x40)

out += RED1;

else if (red < 0x60)

out += RED2;

else if (red < 0x80)

out += RED3;

else if (red < 0xa0)

out += RED4;

else if (red < 0xc0)

out += RED5;

else if (red < 0xe0)

out += RED6;

else

out += RED7;

if (green < 0x20)

out += GREEN0;

else if (green < 0x40)

out += GREEN1;

else if (green < 0x60)

out += GREEN2;

else if (green < 0x80)

out += GREEN3;

else if (green < 0xa0)

out += GREEN4;

else if (green < 0xc0)

out += GREEN5;

else if (green < 0xe0)

out += GREEN6;

else

out += GREEN7;

if (blue < 0x40)

out += BLUE0;

else if (blue < 0x80)

out += BLUE1;

else if (blue < 0xc0)

out += BLUE2;

else

out += BLUE3;

return out;

}1. Red Component (3 bits)

red & 0xe00xe0=11100000in binary- This masks the red value to keep only the top 3 bits

- Result:

0x00,0x20,0x40,0x60,0x80,0xa0,0xc0, or0xe0

2. Green Component (3 bits)

(green & 0xe0) >> 3- First mask green to top 3 bits:

green & 0xe0 - Then shift right by 3 positions:

>> 3 - Result:

0x00,0x04,0x08,0x0c,0x10,0x14,0x18, or0x1c

3. Blue Component (2 bits)

blue >> 6- Shift blue right by 6 positions, keeping only top 2 bits

- Result:

0x00,0x01,0x02, or0x03

4. Combine Components

(red & 0xe0) | ((green & 0xe0) >> 3) | (blue >> 6)- Use bitwise OR to combine all three components

- Each component occupies non-overlapping bit positions

Visual Representation

8-bit Color Encoding (3-3-2)

Bit: 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

[R][R][R][G][G][G][B][B]

Red Green Blue

3 3 2

Example: RGB(0xAB, 0xCD, 0xEF)

Red: 0xAB = 10101011

0xAB & 0xe0 = 10100000 = 0xa0

Green: 0xCD = 11001101

0xCD & 0xe0 = 11000000 = 0xc0

0xc0 >> 3 = 00011000 = 0x18

Blue: 0xEF = 11101111

0xEF >> 6 = 00000011 = 0x03

Result: 0xa0 | 0x18 | 0x03 = 0xbb

Performance Analysis

Branching Version (Slow)

unsigned char quantize_prior(unsigned char red, unsigned char green, unsigned char blue) {

unsigned char out = 0;

// Red component - 7 branches!

if (red < 0x20)

out += RED0;

else if (red < 0x40)

out += RED1;

else if (red < 0x60)

out += RED2;

else if (red < 0x80)

out += RED3;

else if (red < 0xa0)

out += RED4;

else if (red < 0xc0)

out += RED5;

else if (red < 0xe0)

out += RED6;

else

out += RED7;

// Green component - 7 more branches!

if (green < 0x20)

out += GREEN0;

else if (green < 0x40)

out += GREEN1;

// ... more branches

// Blue component - 3 more branches!

if (blue < 0x40)

out += BLUE0;

else if (blue < 0x80)

out += BLUE1;

else if (blue < 0xc0)

out += BLUE2;

else

out += BLUE3;

return out;

}Problems:

- 17 conditional branches total

- Unpredictable execution path (depends on input values)

- Branch mispredictions cause pipeline stalls

- Inconsistent performance (some inputs faster than others)

Branchless Version (Fast)

unsigned char quantize(unsigned char red, unsigned char green, unsigned char blue) {

return (red & 0xe0) | ((green & 0xe0) >> 3) | (blue >> 6);

}Advantages:

-

Zero branches - always executes the same instructions

-

Predictable execution time - same performance for all inputs

-

Better CPU pipeline utilization - no stalls

-

Higher instruction-level parallelism - operations can be pipelined

-

777-bits → cmu low level course

General Principles of Branchless Programming

1. Replace Conditionals with Arithmetic

Instead of:

if (x > 0)

return x;

else

return -x;Use:

return (x ^ (x >> 31)) - (x >> 31); // Branchless abs()2. Use Bitwise Operations for Ranges

Instead of:

if (x >= 0 && x < 8)

return x;

else

return 0;Use:

return x & 7; // x % 8, but faster3. Use Lookup Tables for Complex Mappings

Instead of:

if (x == 0) return 0;

else if (x == 1) return 1;

else if (x == 2) return 4;

// ... many more branchesUse:

static const int lookup[] = {0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49};

return lookup[x & 7];4. Use Conditional Moves When Possible

Instead of:

if (condition)

result = value1;

else

result = value2;Use:

result = condition ? value1 : value2; // Often compiles to conditional moveWhen to Use Branchless Techniques

Good Candidates:

- Hot loops (executed millions of times)

- Image/video processing (pixel-by-pixel operations)

- Cryptographic functions (constant-time requirements)

- Real-time systems (predictable performance needed)

When Branches Are Acceptable:

- Cold code (rarely executed)

- Complex logic (hard to make branchless)

- Readable code (maintainability over performance)

- Compiler optimizations (modern compilers are good at branch prediction)

Advanced Branchless Techniques

1. SIMD Branchless Operations

##include <immintrin.h>

// Process 8 pixels simultaneously

__m256i quantize_simd(__m256i red, __m256i green, __m256i blue) {

__m256i red_quantized = _mm256_and_si256(red, _mm256_set1_epi32(0xe0));

__m256i green_quantized = _mm256_srli_epi32(_mm256_and_si256(green, _mm256_set1_epi32(0xe0)), 3);

__m256i blue_quantized = _mm256_srli_epi32(blue, 6);

return _mm256_or_si256(_mm256_or_si256(red_quantized, green_quantized), blue_quantized);

}2. Bit Manipulation Tricks

// Branchless min/max

int min_branchless(int a, int b) {

return b ^ ((a ^ b) & -(a < b));

}

int max_branchless(int a, int b) {

return a ^ ((a ^ b) & -(a < b));

}

// Branchless sign function

int sign_branchless(int x) {

return (x > 0) - (x < 0);

}Key Takeaways

- Branches are expensive due to branch mispredictions and pipeline stalls

- Bitwise operations can often replace conditional logic

- Predictable execution is crucial for performance-critical code

- Profile before optimizing - not all branches are performance bottlenecks

- Balance readability with performance - sometimes branches are clearer

Next Steps

- Profile your code to identify branch mispredictions

- Experiment with bitwise operations to replace conditionals

- Use SIMD for vectorized branchless operations

- Study assembly output to understand compiler optimizations

- Benchmark different approaches to measure real performance gains

The key insight: Modern CPUs are optimized for predictable, linear execution. Branchless code exploits this by eliminating the unpredictability of conditional jumps.

What is a cache line (brief explanation)

A cache line is the smallest unit of data that a CPU cache transfers between main memory (RAM) and the cache.

- Typically 32 to 128 bytes in size.

- When the CPU needs data, it fetches an entire cache line (not just a single variable) into the cache.

- This works because of spatial locality: if the program accesses one memory location, it’s likely to access nearby locations soon.

👉 In short: a cache line is a fixed-size block of memory that serves as the fundamental unit of caching.

Algorithms for Modern Hardware - Algorithmica

Why are there multiple levels of CPU cache

Intel Skylake Here’s how to count cache lines (and sets) from the specs. Formulas:

Number of lines = cache_size_bytes / line_size_bytes Number of sets = number_of_lines / associativity = cache_size / (line_size × associativity) Line offset bits = log2(line_size); index bits = log2(number_of_sets)

Computed: L1 Data: 32 KB, 64 B/line, 8‑way lines = 32×1024 / 64 = 512 sets = 512 / 8 = 64 bits: offset = 6, index = 6 L1 Instruction: 32 KB, 64 B/line, 8‑way lines = 512 sets = 64 bits: offset = 6, index = 6 L2: 256 KB, 64 B/line, 4‑way lines = 256×1024 / 64 = 4096 sets = 4096 / 4 = 1024 bits: offset = 6, index = 10

like a tradeoff btw shipping, cost, time , quantity

Understanding CPU caches

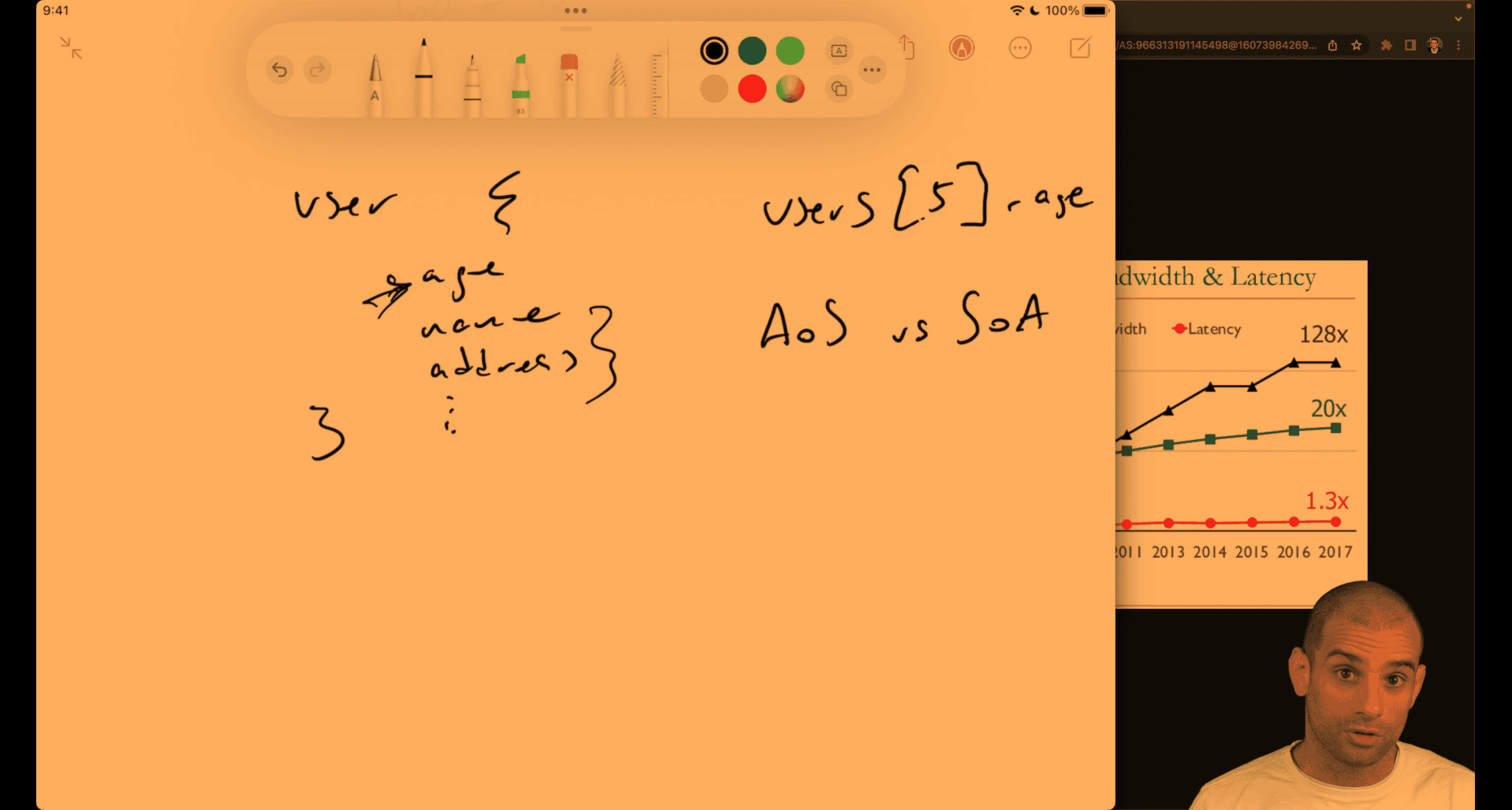

concept:

- array of struct vs struct of array

cpu cache will auto detecting or gussing the next item near the memory

- pointer chasing , like orm(relationship database), object point to another object

cache may have that pointe, or may be not

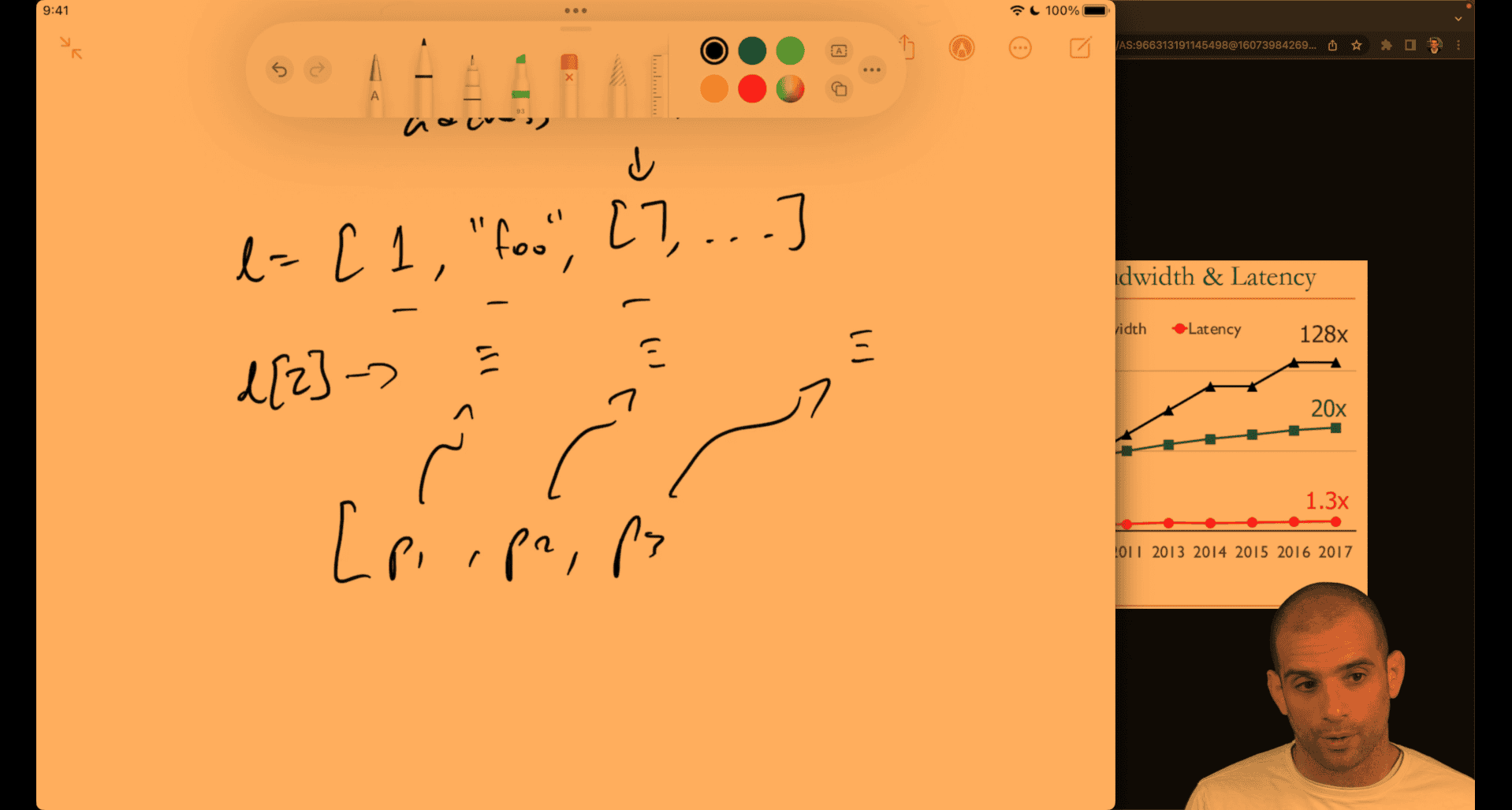

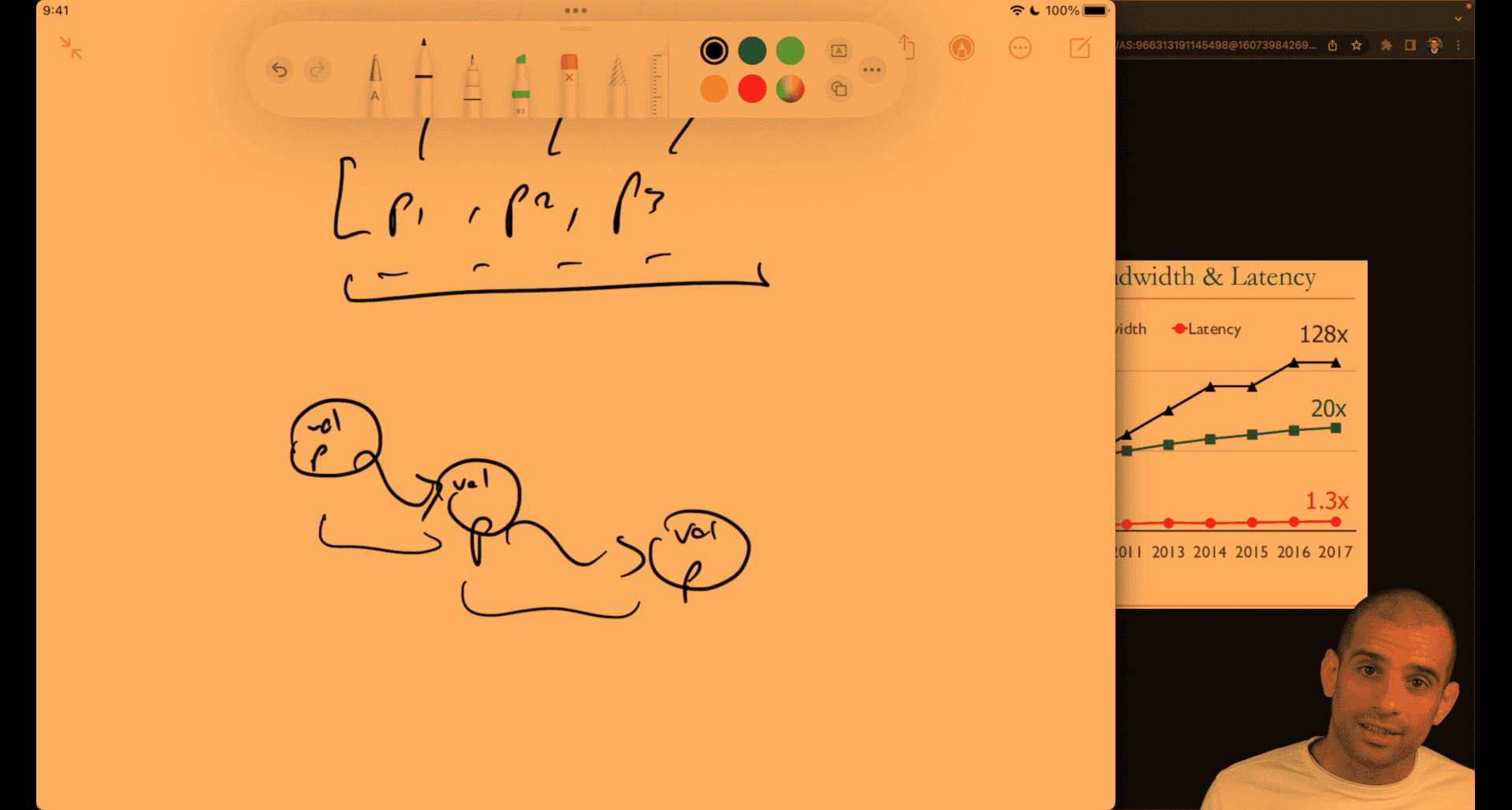

p1 → python object, how it keep the pointer still be O(1) → l[2] → python object pointer to python number

python will also preconstruct small number first

python data structure use pointer as their interface to different type(pointer chasing effect ) so they are relatively slow

numpy → type first → faster

usually when space is larger , time also slower, there is cache utilization in algorithm

e.g. hash map implementation, 2 different to do , two different key to same value ; chaining way ; open addressing

linked list as well, unless you preconfig close memory for each other to make it more efficient

linked list as well, unless you preconfig close memory for each other to make it more efficient

list → lisp

array approach is better

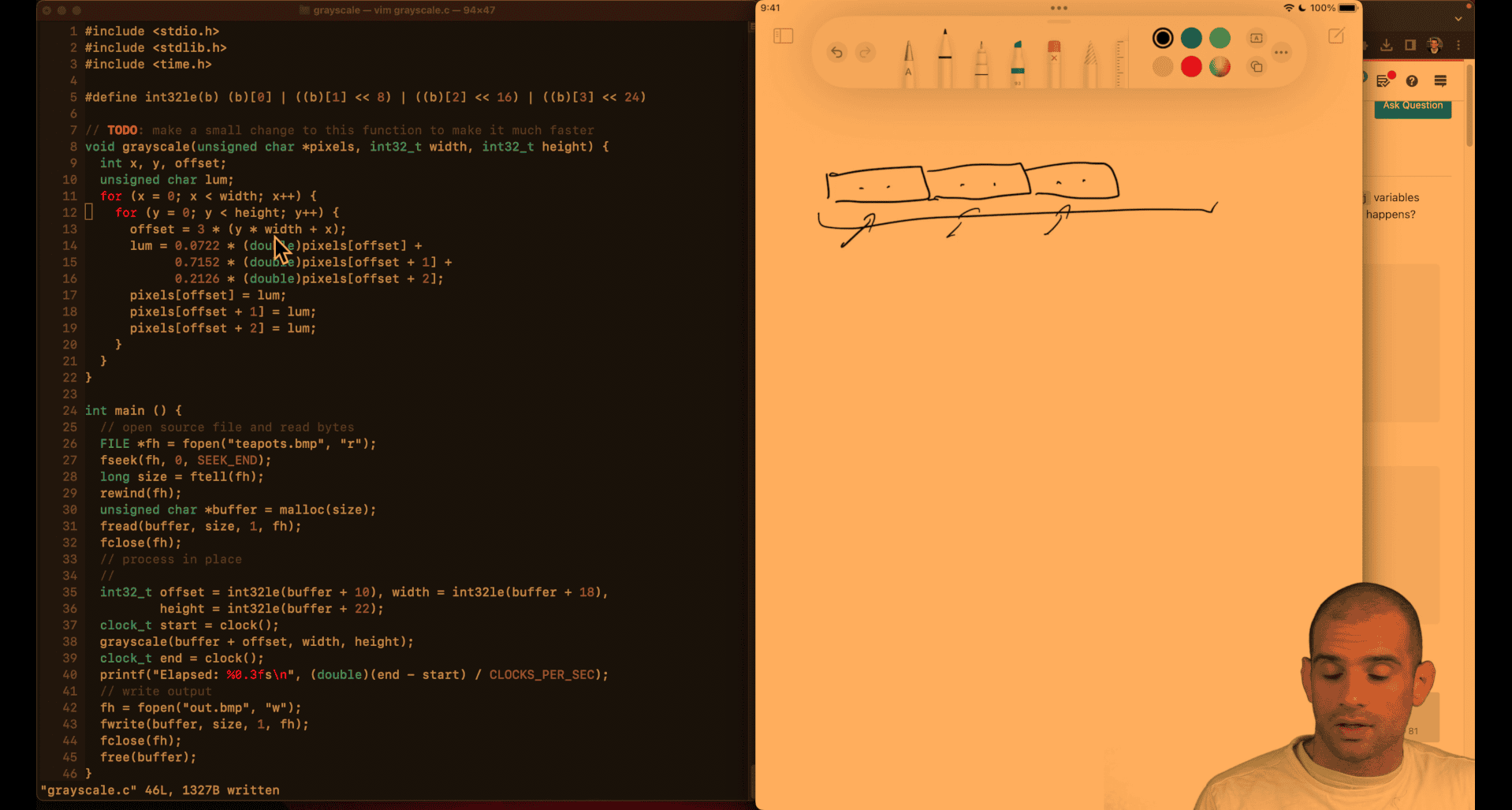

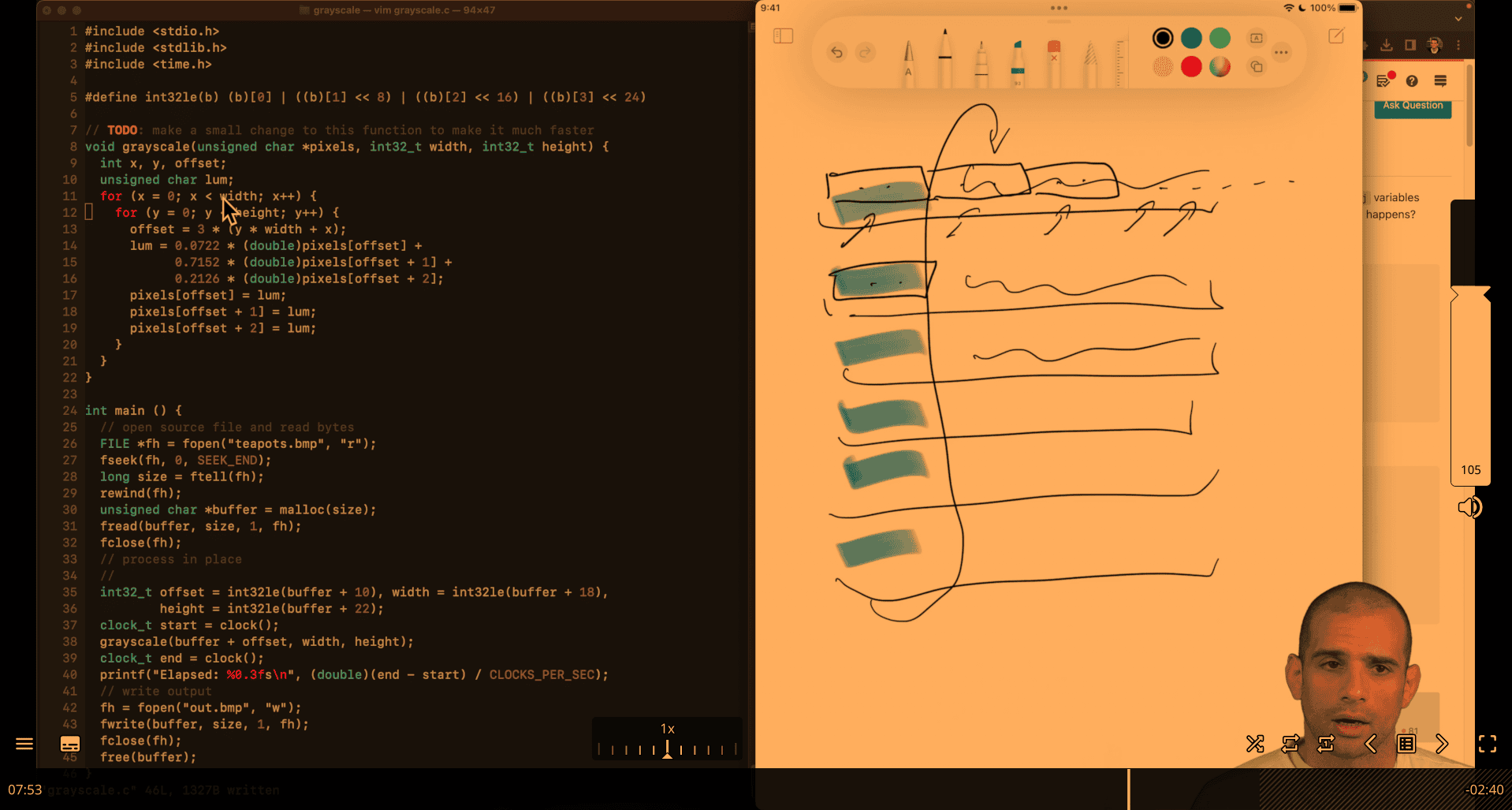

Grayscale speedup

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#define int32le(b) (b)[0] | ((b)[1] << 8) | ((b)[2] << 16) | ((b)[3] << 24)

// TODO: make a small change to this function to make it much faster

void grayscale(unsigned char *pixels, int32_t width, int32_t height) {

int x, y, offset;

unsigned char lum;

for (x = 0; x < width; x++) {

for (y = 0; y < height; y++) {

offset = 3 * (y * width + x);

lum = 0.0722 * (double)pixels[offset] +

0.7152 * (double)pixels[offset + 1] +

0.2126 * (double)pixels[offset + 2];

pixels[offset] = lum;

pixels[offset + 1] = lum;

pixels[offset + 2] = lum;

}

}

}

int main () {

// open source file and read bytes

FILE *fh = fopen("teapots.bmp", "r");

fseek(fh, 0, SEEK_END);

long size = ftell(fh);

rewind(fh);

unsigned char *buffer = malloc(size);

fread(buffer, size, 1, fh);

fclose(fh);

// process in place

//

int32_t offset = int32le(buffer + 10), width = int32le(buffer + 18),

height = int32le(buffer + 22);

clock_t start = clock();

grayscale(buffer + offset, width, height);

clock_t end = clock();

printf("Elapsed: %0.3fs\n", (double)(end - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC);

// write output

fh = fopen("out.bmp", "w");

fwrite(buffer, size, 1, fh);

fclose(fh);

free(buffer);

}Measuring cache performance with perf and cachegrind

Valgrind Home or Perf perf need linux native for more detail, primer said it cann’t work on vm

first , it is a clomn first iteration, not row first iteration → slower

c - Why does the order of the loops affect performance when iterating over a 2D array? - Stack Overflow it seem the speed is depend on programming languages

column first or row first

fit in cache line → row, kind of like a putting a line of ikea stuff

fit in cache line → row, kind of like a putting a line of ikea stuff

- just exchange x and y line → row based → fit the cache line → faster

pointer-chase

import csv

import datetime

import math

import time

class Address(object):

def __init__(self, address_line, zipcode):

self.address_line = address_line

self.zipcode = zipcode

class DollarAmount(object):

def __init__(self, dollars, cents):

self.dollars = dollars

self.cents = cents

class Payment(object):

def __init__(self, dollar_amount, time):

self.amount = dollar_amount

self.time = time

class User(object):

def __init__(self, user_id, name, age, address, payments):

self.user_id = user_id

self.name = name

self.age = age

self.address = address

self.payments = payments

def average_age(users):

total = 0

for u in users.values():

total += u.age

return total / len(users)

def average_payment_amount(users):

amount = 0

count = 0

for u in users.values():

count += len(u.payments)

for p in u.payments:

amount += float(p.amount.dollars) + float(p.amount.cents) / 100

return amount / count

def stddev_payment_amount(users):

mean = average_payment_amount(users)

squared_diffs = 0

count = 0

for u in users.values():

count += len(u.payments)

for p in u.payments:

amount = float(p.amount.dollars) + float(p.amount.cents) / 100

diff = amount - mean

squared_diffs += diff * diff

return math.sqrt(squared_diffs / count)

def load_data():

users = {}

with open('users.csv') as f:

for line in csv.reader(f):

uid, name, age, address_line, zip_code = line

addr = Address(address_line, zip_code)

users[int(uid)] = User(int(uid), name, int(age), addr, [])

with open('payments.csv') as f:

for line in csv.reader(f):

amount, timestamp, uid = line

payment = Payment(

DollarAmount(dollars=int(amount)//100, cents=int(amount) % 100),

time=datetime.datetime.fromisoformat(timestamp))

users[int(uid)].payments.append(payment)

return users

if __name__ == '__main__':

t = time.perf_counter()

users = load_data()

print(f'Data loading: {time.perf_counter() - t:.3f}s')

t = time.perf_counter()

assert abs(average_age(users) - 59.626) < 0.01

assert abs(stddev_payment_amount(users) - 288684.849) < 0.01

assert abs(average_payment_amount(users) - 499850.559) < 0.01

print(f'Computation {time.perf_counter() - t:.3f}s')optimized version:

import csv

import math

import time

def average_age(ages):

total = 0

for x in ages:

total += x

return total / len(ages)

def average_payment_amount(payments):

total = 0

for dollars, cents in payments: