- csprimer-computersystem-concept3

- Programming C

- Explanation:

- Example:

- 🔢 What is

0xffffffff? - 🧠 Signed vs Unsigned Int in C

- ⚙️ Two’s Complement Concept

- ✅ Why

0xffffffff= -1 in signed int - 🚫 Why the Loop Breaks

- Summary

- 🔍 What does it do?

- 🔥 Why is it faster?

- 🧠 Example:

n = 0b10110000 - 💡 Why

n & (n - 1)clears the lowest set bit? - Summary:

- 🧠 What is

popcnt? - ✅ Why your teacher used

-march=nativeand-O3 - 🧩 What does the assembly mean?

- 🚀 Summary

- 🧠 The Core Idea: Parallel Byte Aggregation

- ⚡ Example: Parallel 16-bit Pairing

- 🚀 In SIMD Hardware:

- 🧪 Summary:

- 🧰 Python can’t truly do this in parallel, but…

- 🧠 What Is a Divide and Conquer Algorithm?

- ✅ Classic Examples

- 🧮 For Byte Summing?

- 👇 In simple Python example:

- Script Breakdown

- Example Usage

- Why It Can Be Used for Speed Testing (Profiling)

- How It Acts Like a Profiler

- Example Scenario

- Limitations

- Improvements for Better Profiling

- Conclusion

- Overview of the Program

- Code Breakdown

- How It Fits with the Bash Script

- Key C Concepts for Beginners

- Example: Completing

ispangram - Running the Program

- Sample Run

- Why This Code?

- Next Steps

- the different C compiler , gcc vs clang

- Key Features of

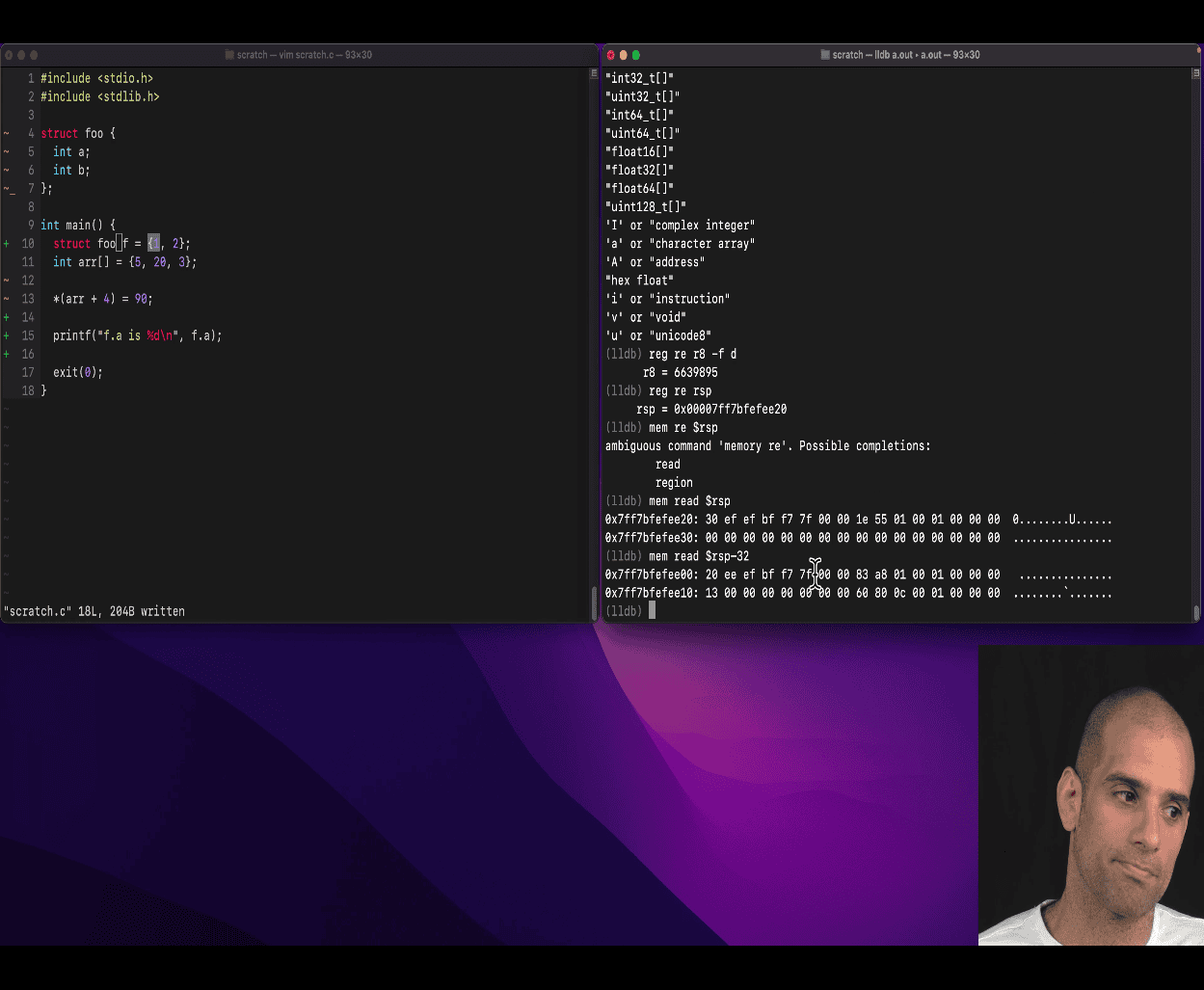

<stdint.h>- 1. Arrays and Pointers in C

- 2. Array Indexing:

arr[3] - 3. Pointer Arithmetic:

*(arr + 3) - 4. Why

arr[3]==*(arr + 3)? - 5. Example from Your Code

- 6. What Your Teacher Is Teaching

- 7. Key Takeaways

- 8. A Visual Explanation

- 9. Practice to Reinforce

- 1. Preprocessor Directives

- 2. Conditional Compilation

- 3. The Role of the

DEBUGMacro - 4. The

fprintf(stderr, "error\n")Line - 5. Why This Matters

- 6. Fixing the Code

- 7. How

DEBUGIs Set - 8. Example Compilation Scenarios

- 9. Broader Lesson

- 10. Practice to Reinforce

- 11. Connection to Pointers (from Your Previous Question)

- 1. Overview of Structs in C

- 2. Key Concepts Your Teacher Is Teaching

- 3. Memory Address Calculation:

0x7ffe6b1f9ea0to0x7ffe6b1f9eb8 - 4. Broader Lessons from Your Teacher

- 5. Practice to Reinforce

- 6. Key Takeaways

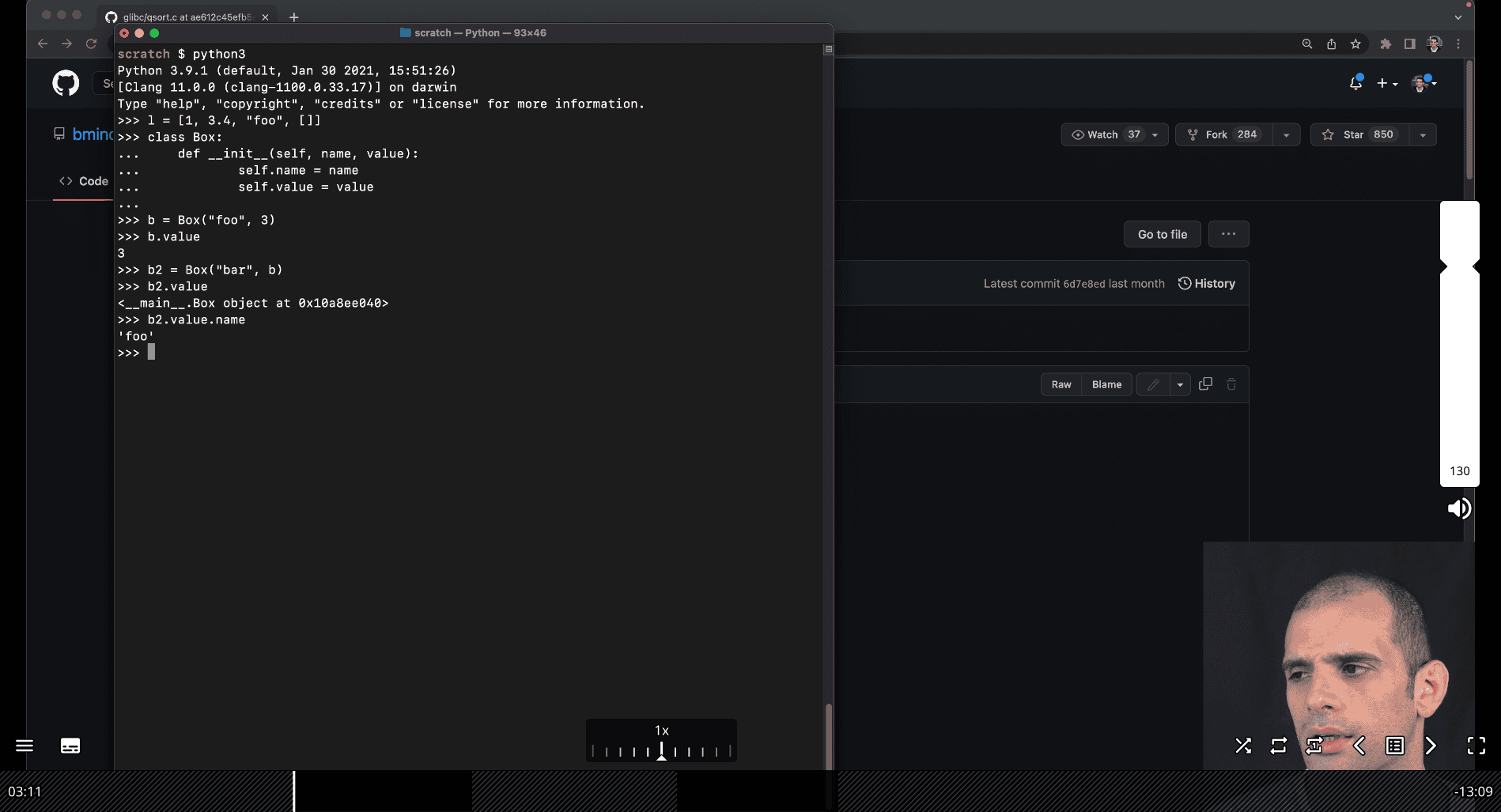

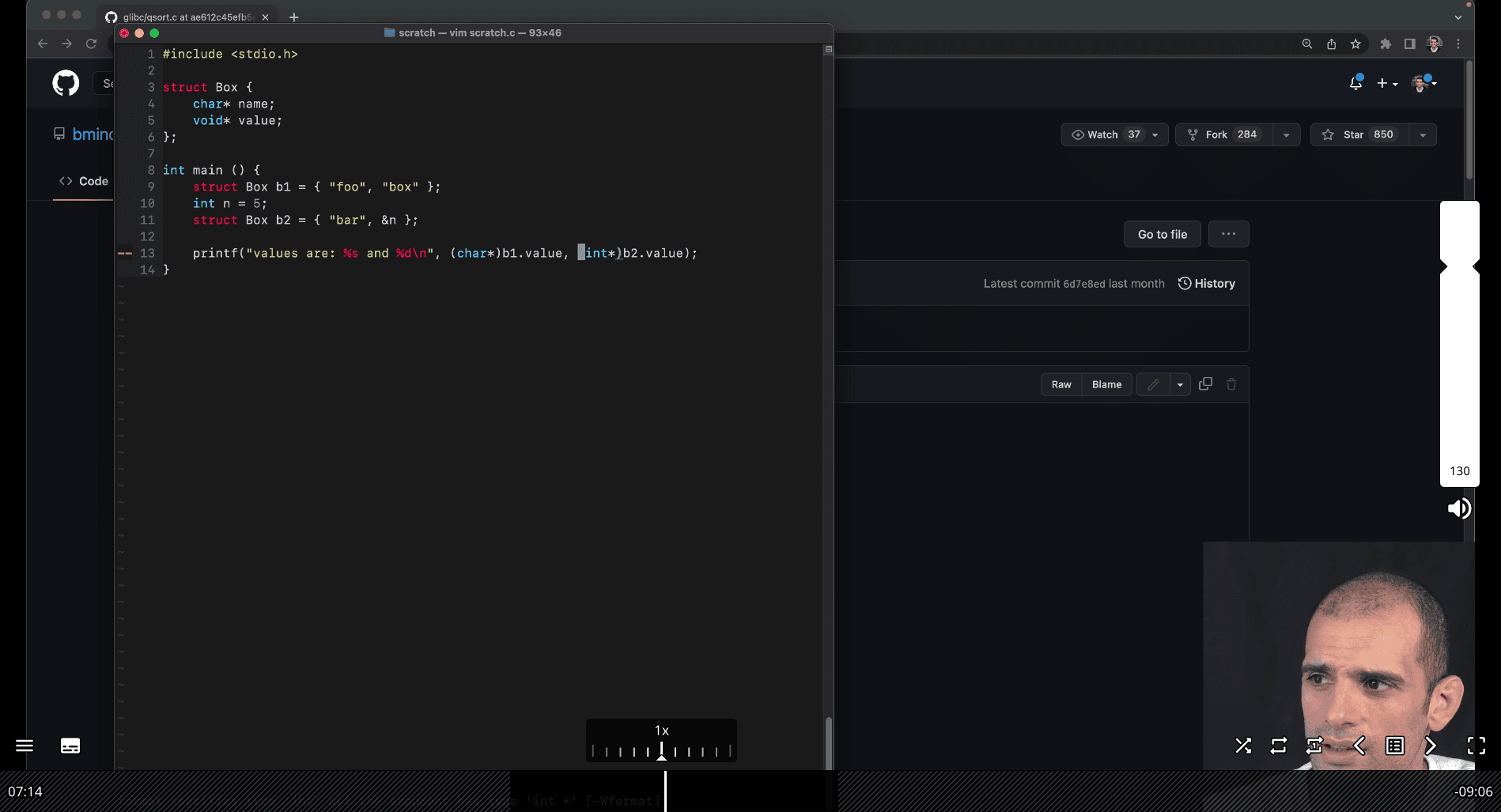

- Context Setup

- 1.

(int*)b2.value - 2.

*(int*)b2.value - Key Difference

- Why This Happens

- Correct Approach

- Summary

- 🧠 What Your Teacher Is Teaching:

- 🔍 Stack Memory Layout (Key Idea)

- 💥 Why Overwriting Happens:

- ✅ What Your Teacher’s Trying to Teach:

- 🧪 Why This Is “A Small Chance” Case

- 🧠 Takeaway Message:

- 📦 What Is the Stack?

- 📐 Key Characteristics of the Stack

- 🧱 Stack Frame Layout (per function call)

- 🧪 Example: Stack Frame Visualization

- 🤯 Why Memory Bugs Happen

- 🎯 What Your Teacher Is Demonstrating

- 🛡️ Tools to Catch These Bugs

- 👣 Summary

- 🧠 What Is

$rsp? - 🔍 What Does This Do?

- 📐 Why It’s Useful

- 🔧 Try It Yourself

- 🧭 Summary

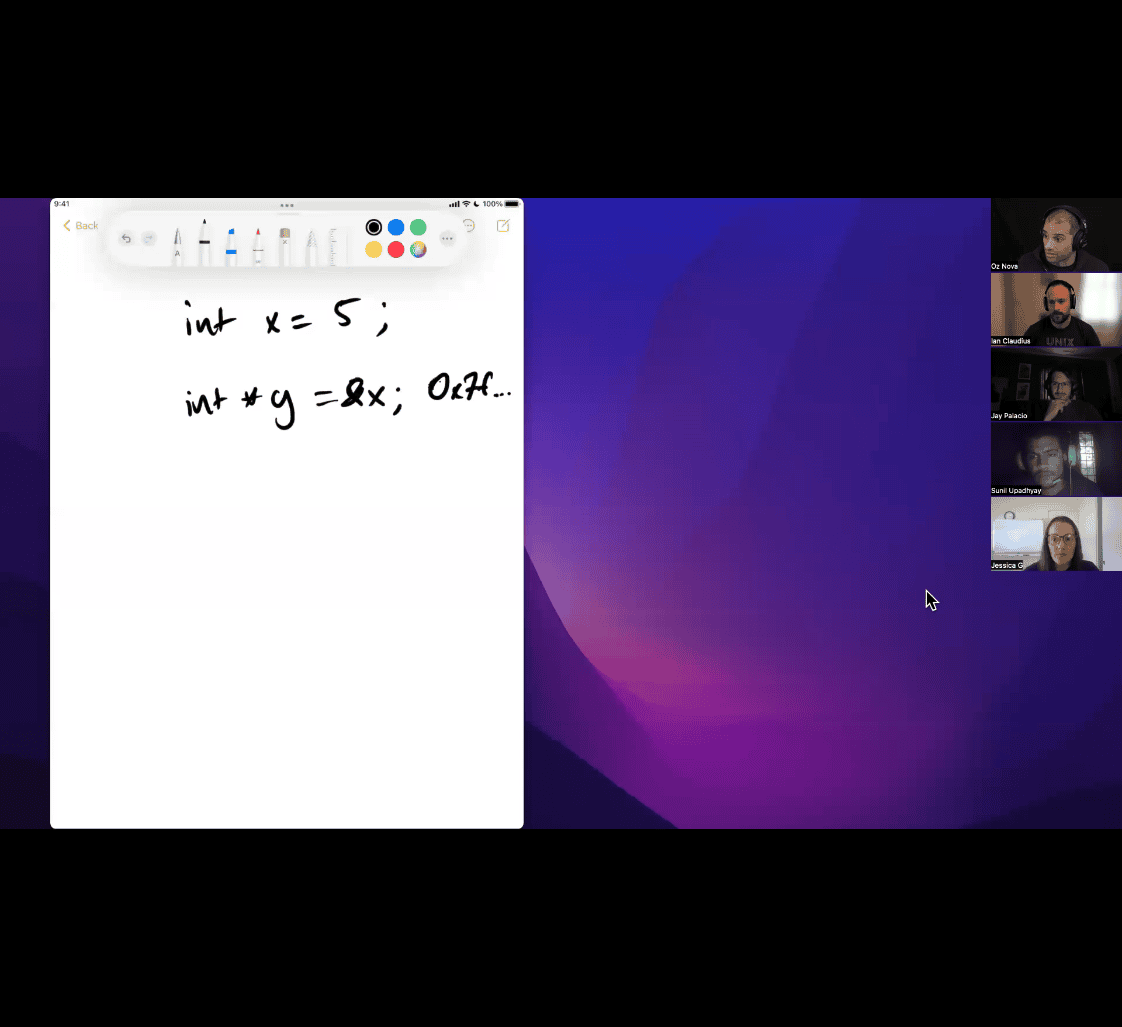

- 🧠 1.

int x = 5;→ What happens? - 📦 2. What about

&x(the address of x)? - 🧠 3. Visualizing

x,y, andz - 📍 Why This Matters

- 🔄 Address Arithmetic Note

- ✅ TL;DR

- 🔍 What is a

void*? - ❌ Pointer Arithmetic Is Not Allowed on

void*(in C) - 🧠 Why Cast to

char*oruint8_t*? - ✅ Summary

- 🔁 What Is a Cast?

- 🧠 Two Main Kinds of Casts

- ⚠️ Why Casts Are Powerful (and Dangerous)

- 🧰 Common Use Cases

- 👎 What You Should Not Do

- 🧠 Cast vs Implicit Conversion

- 🎯 TL;DR Summary

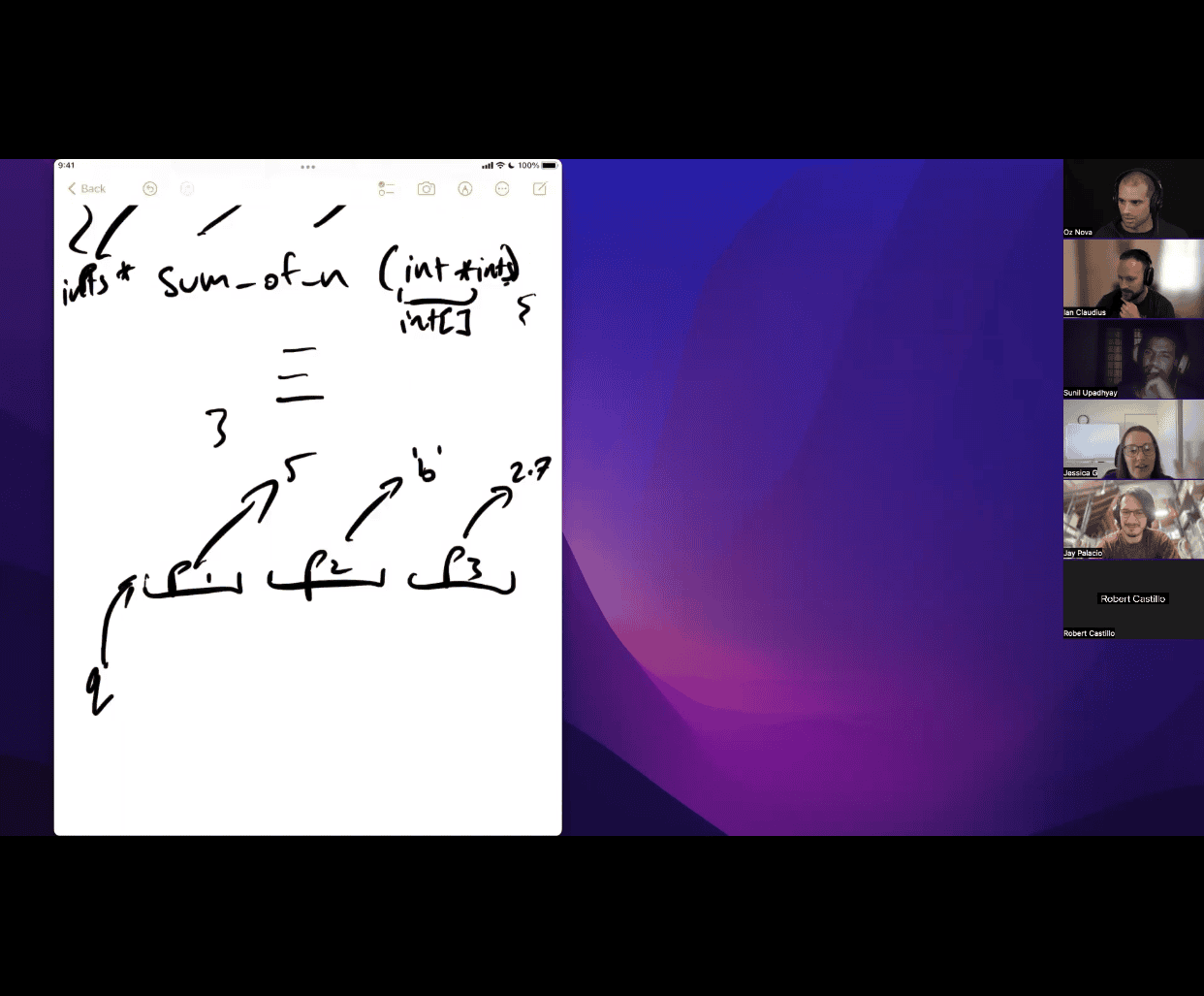

- 🧠 What Is

void **? - ✅ Real Use Case: Generic Memory Setters

- 🧩 Applying to Your Teacher’s Diagram

- 🚨 Why Is This Confusing?

- 🧠 What’s the Takeaway? - 🧠 Part 1: What Does

void* arr;Mean? - 🔁 Now What If You Usevoid** arr;? - ✅ Your Case: Dynamic Array (Generic) - 📦 Example Use Case -void* arr(raw block of memory): -void** arr(array of pointers): - 🔧 So What Is Your Teacher Trying to Do? - 🔍 Final Analogy

- Key Features of

csprimer-computersystem-concept5

csprimer-computersystem-concept3

NASM Tutorial

hackclub/some-assembly-required: 📖 An approachable introduction to Assembly.

- there is two common x64 , inter and att (linux prefer) push → pushq → push to queue

att: movq , movb (b for byte), bl → long byte

movq , q for qute word quart word → 64 bit → quart of 64 , 16

-

subq: substracting 16 from %rsp

-

operator order is difference btw att and intel

-

look at the construction

one text section , loaded in the memory

Programming C

learn x in y minutes C, Go - Hyperpolyglot read c code , linux source code

- high level of struct

- compile , c knowledge with machine

hello world in c :

int main() {} → why int a linux culture → 0 mean successful like work && run bash order

if return 1; → not , it will not run as successful, can && after

return -1 → assertion fail → fail reminder in terminal

int bitcount(int n) { int count = 0; while (n){

} }

in c , 0 mean true , 1 → false

- don’t have boolean in c , so using

while(n)-> keep runing while n is not 0

n & 0x01 is a bitwise AND operation that checks whether the least significant bit (LSB) of n is 1 or 0.

Explanation

0x01is hexadecimal for00000001in binary.n & 0x01comparesnwith00000001using bitwise AND:- If the LSB of

nis1, the result is1. - If the LSB is

0, the result is0.

- If the LSB of

Example

n = 5; // binary: 0101

n & 0x01 = 1 // because the LSB is 1This is commonly used to count the number of 1s in a binary number (also known as the Hamming weight or population count).

Also, your function is missing a return statement. Here’s the corrected version:

int bitcount(int n) {

int count = 0;

while (n) {

if (n & 0x01) {

count += 1;

}

n >>= 1;

}

return count;

}Let me know if you want a version that’s more efficient.

as there is only 1 and 0 out there , so if there is 1 in the lsb , least significant bit → shift right until 0

int bitcount(int n) { int count = 0; while (n) { count += n & 0x01; n >>= 1; } return count; }

-

refactor as 0 dont affect count, add them all in here lol

int main() { assert(bitcount(0) == 0); assert(bitcount(1) == 1); assert(bitcount(3) == 2); assert(bitcount(8) == 1); // harder case: assert(bitcount(0xffffffff) == 32); printf("OK\n"); }

assert(bitcount(0xffffffff) == 32); this break the while(n) loop , so the n != 0 for 0xffffffff

🔢 What is 0xffffffff?

In binary, 0xffffffff is:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 // 32 bits

That’s all bits set to 1 — which equals 4294967295 in unsigned interpretation.

🧠 Signed vs Unsigned Int in C

intis signed (can represent negative and positive numbers).- It uses two’s complement representation to handle negatives.

⚙️ Two’s Complement Concept

In two’s complement, the highest bit (leftmost bit) is the sign bit:

0xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx→ positive1xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx→ negative

To get the negative value of a binary number:

- Invert all the bits

- Add 1

So in 32-bit signed int:

0x00000001→ 10x7fffffff→ 2,147,483,647 (max signed int)0x80000000→ -2,147,483,648 (min signed int)0xffffffff→ -1

✅ Why 0xffffffff = -1 in signed int

Let’s apply two’s complement:

0xffffffff=11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111- Invert:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 - Add 1:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000001→ that’s1 - So original =

-1

Hence, 0xffffffff is interpreted as -1 in a signed int.

🚫 Why the Loop Breaks

Right-shifting signed -1:

-1 >> 1→ still-1, because the sign bit (1) is preserved.- So

nnever becomes0, andwhile (n)becomes infinite loop.

Summary

| Hex | Binary (32-bit) | Interpreted as |

|---|---|---|

0xffffffff | 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 | -1 (signed int) |

4294967295 (unsigned int) |

So: same bits, different meaning depending on signed vs unsigned.

Let me know if you’d like a visual to reinforce this!

int bitcount(unsigned n) { int count = 0; while (n) { count += n & 0x01; n >>= 1; } return count; }

int n → unsigned → fixed

before using belew , it loop 32 times for case 0xfff … == 32

- x & x-1 → deleted the rightmost bit of x using bitwise &

Excellent question — this is a classic bit manipulation trick often called Brian Kernighan’s Algorithm.

Excellent question — this is a classic bit manipulation trick often called Brian Kernighan’s Algorithm.

🔍 What does it do?

This line:

n &= (n - 1);clears the lowest set bit (the rightmost 1) in n.

Each time this happens, we increment count.

So instead of looping through all 32 bits, we loop only through the number of set bits.

🔥 Why is it faster?

Let’s compare with your previous method:

Previous method

while (n) {

count += n & 1;

n >>= 1;

}- Always does up to 32 iterations, checking each bit one-by-one.

New method

while (n) {

n &= (n - 1);

count++;

}- Does only as many iterations as there are 1s in

n.

🧠 Example: n = 0b10110000

Set bits: 3 Old loop → 8 iterations New loop → 3 iterations ✔️

💡 Why n & (n - 1) clears the lowest set bit?

Let’s take an example:

n = 0b10110000

n - 1 = 0b10101111

---------------------

n & (n-1)= 0b10100000 ← rightmost 1 cleared

So each iteration removes one 1, getting us closer to 0 faster.

Summary

| Method | Iterations Needed | Performance Benefit |

|---|---|---|

n >>= 1 | Up to 32 | Slower for sparse bits |

n &= (n-1) | Only set bits (Hamming weight) | Faster overall |

Your teacher’s version is more efficient, especially when n has few set bits. It’s a smart use of bitwise logic.

advanced C : compiler →

pop count (compiler) population count

cc -O3 -fomit-frame-pointer -march=native -c bitcount.c

objdump -d bitcount.o

🧠 What is popcnt?

popcntis a CPU instruction that counts the number of1bits (set bits) in a binary number.- It’s built into modern CPUs (like Intel and AMD).

- It’s extremely fast — much faster than any loop.

Think of it as a “hardware-accelerated bitcount.”

✅ Why your teacher used -march=native and -O3

-O3: Tells the compiler to fully optimize the code.-march=native: Allows the compiler to use CPU-specific features, likepopcnt.

So when the compiler sees your function:

int bitcount(unsigned n) {

int count = 0;

while (n) {

n &= (n-1);

count++;

}

return count;

}Instead of compiling a loop, it says:

“Oh! This is just a popcount — I’ll replace it with the

popcntinstruction.”

🧩 What does the assembly mean?

0: 31 c0 xor %eax, %eax // set EAX = 0 (clear return value register)

2: f3 0f b8 c7 popcnt %edi, %eax // EAX = popcount(EDI)

6: c3 ret // return

Let’s break it down:

| Assembly | Meaning |

|---|---|

xor %eax, %eax | Clear the eax register (set to 0) |

popcnt %edi, %eax | Count bits in edi and put result in eax |

ret | Return from function |

Registers:

%edi: where the first argument (unsigned n) is passed (in 64-bit calling convention).%eax: where the return value is stored.

🚀 Summary

- The compiler recognized your bitcount function and replaced it with a single fast

popcntCPU instruction. - This is only possible with optimization flags (

-O3 -march=native) and on CPUs that supportpopcnt.

So this is your teacher showing you:

“Writing clever code is cool, but modern compilers and CPUs can do even better!”

Let me know if you want a visual of how registers or popcnt work internally.

adding inline compiler wtf

#include <nmintrin.h>

__builtin_popcount(n) Counts 1-bits efficiently <nmmintrin.h> Enables SSE4.2 intrinsics like popcnt Replaces manual loop Cleaner, faster, compiler-optimized

- using mechine code instruction → more optimize

as it is usign mechine instruction , not all computer have popcount , so if compile didn’t set to march = native , it will just use other assembly way

no loop in in the assembly

primer suggesting this book:

Hacker’s Delight

there is counting tips about bitw

Parallel way to count the bit from pair

32 → 16 → 4 → 2 pair 2 bit and sum

I am not gpt genthis right in below

Ah! If your teacher mentioned that the algorithm allows you to “run in parallel,” then he’s likely referring to an approach inspired by SIMD-style or parallel prefix sum techniques.

🧠 The Core Idea: Parallel Byte Aggregation

When decoding a multi-byte little-endian number (e.g. a4 01 00 00), the normal method is sequential:

value = b[0] + (b[1] << 8) + (b[2] << 16) + (b[3] << 24)This is inherently sequential because each shift depends on the byte’s position.

But with parallel processing, you can:

- Split the bytes into groups (e.g. 2-byte chunks)

- Perform operations on those chunks in parallel

- Combine the partial results later

⚡ Example: Parallel 16-bit Pairing

Let’s say you have 4 bytes:

bs = [a4, 01, 00, 00]

Instead of:

a4 + 01 << 8 + 00 << 16 + 00 << 24You could do:

-

Group into 2-byte chunks:

chunk1 = a4 01 => little-endian: 0x01a4 chunk2 = 00 00 => 0x0000 -

Then compute:

value = chunk1 + (chunk2 << 16)

You’re now doing fewer additions, and this structure can be parallelized in low-level or SIMD hardware (e.g., SSE/AVX).

🚀 In SIMD Hardware

On CPUs that support SIMD (like Intel with AVX), operations like “multiply and accumulate” or “shift and add” on multiple 16- or 32-bit integers can be vectorized, meaning done in parallel registers.

Even in GPU programming (CUDA, OpenCL), this matters.

🧪 Summary

Your teacher is hinting at an algorithm that makes endian conversion more parallel-friendly:

| Feature | Explanation |

|---|---|

| ✅ Break into 2-byte chunks | Reduces loop iterations |

| ✅ SIMD-friendly | You can shift/add in parallel lanes |

| ✅ More efficient for large arrays | Works well in image or video data |

| ✅ CPU/GPU optimization | Used in compilers and video codecs |

🧰 Python can’t truly do this in parallel, but

You could simulate the logic and understand how it reduces dependency per byte.

Want me to show you this idea with an example that compares standard vs 2-byte parallel-style summing in Python?

Ah! You’re thinking of Divide and Conquer algorithms. (That’s the correct spelling 😊)

🧠 What Is a Divide and Conquer Algorithm?

Divide and Conquer is a strategy to solve complex problems by:

- Divide — Breaking the problem into smaller subproblems.

- Conquer — Solving each subproblem recursively (or in parallel).

- Combine — Merging the solutions of subproblems to get the final answer.

✅ Classic Examples

| Problem | How Divide & Conquer Works |

|---|---|

| Merge Sort | Divide the array, sort both halves recursively, then merge the sorted halves |

| Quick Sort | Partition the array, then sort left and right parts recursively |

| Binary Search | Divide search space in half each time |

| Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) | Split signals, apply FFT recursively, then combine frequency results |

| Matrix Multiplication (Strassen) | Break matrix into quadrants, multiply submatrices recursively |

🧮 For Byte Summing?

Yes — your teacher might be suggesting a Divide and Conquer approach to summing bytes, like:

- Pair 2 bytes together and form small integers

- Sum pairs recursively

- Combine results

This lets you parallelize the summing, especially if:

- You’re reading huge binary files

- You’re processing pixels or data blocks

- You’re optimizing for SIMD/CPU threads

👇 In simple Python example

def le_dc(bs): # Divide and Conquer for little-endian bytes

if len(bs) == 1:

return bs[0]

mid = len(bs) // 2

left = le_dc(bs[:mid])

right = le_dc(bs[mid:])

return left + (right << (8 * mid))Same result as the loop-based method, but this can be done in parallel in theory, because left and right are independent until the final shift + add.

Would you like a visual animation or simple diagram of how this divide-and-conquer version works compared to normal summing?

- primer mention : What Is a Divide and Conquer Algorithm?

Divide and Conquer is a strategy to solve complex problems by:

Divide — Breaking the problem into smaller subproblems.

Conquer — Solving each subproblem recursively (or in parallel).

Combine — Merging the solutions of subproblems to get the final answer.

Let’s break down the provided Bash script and explain its functionality, focusing on how it can be used for speed testing (profiling) in a Unix environment.

Script Breakdown

#!/usr/bin/env bash- Shebang: Specifies that the script should be executed using the Bash interpreter found in the user’s environment path. Using

/usr/bin/env bashensures portability across systems where Bash might be installed in different locations.

set -euo pipefail- Shell Options:

-e: Exits immediately if any command fails (non-zero exit status).-u: Treats unset variables as errors and exits.-o pipefail: Ensures that a pipeline fails if any command in the pipeline fails, not just the last one.

- Purpose: These settings make the script robust by catching errors early and preventing unexpected behavior.

IFS=$'\n\t'- Internal Field Separator (IFS): Sets the field separator to newline (

\n) and tab (\t). This controls how Bash splits words during command substitution and loops, ensuring that spaces in input/output are preserved correctly. - Purpose: Prevents issues when handling file contents or arguments with spaces.

trap "kill 0" SIGINT- Trap: Sets up a signal handler for

SIGINT(e.g., when the user pressesCtrl+C). The commandkill 0sends the signal to all processes in the current process group, effectively terminating the script and any child processes it spawned. - Purpose: Ensures clean termination of the script and its subprocesses when interrupted.

if [[ "$#--1-|" < 1 ]]; then

echo "Usage: ./test.sh cmd" >&2

exit 1

fi- Argument Check:

$#: Number of command-line arguments passed to the script.- If fewer than 1 argument is provided, it prints a usage message to stderr (

>&2) and exits with status1(indicating an error).

- Purpose: Ensures the script is called with at least one argument (the command to test).

diff <(cat cases.txt | eval "(time $@)") pangrams.txt- Main Command:

cat cases.txt: Reads the contents ofcases.txt(presumably a file containing test inputs, such as strings or pangrams).|: Pipes the output ofcat cases.txtto the next command.eval "(time $@)":$@: Represents all command-line arguments passed to the script (e.g.,python3 some_script.py).time: A Unix utility that measures the execution time of the command that follows.eval: Evaluates the string(time $@)as a command. This allows the script to run the user-provided command (e.g.,python3 some_script.py) with thetimecommand prepended, measuring its execution time.- The parentheses

(...)in theevalensure that thetimeoutput (timing statistics) is captured along with the command’s output.

<(...): Process substitution. The output of the command inside<(...)(i.e., the output ofcat cases.txt | eval "(time $@)") is treated as a temporary file.diff: Compares the output of the command (from process substitution) with the contents ofpangrams.txt(presumably a file containing expected outputs).

- Purpose: Runs the specified command with input from

cases.txt, measures its execution time, and compares its output topangrams.txtto verify correctness.

Example Usage

The script is invoked as:

./test.sh python3 some_script.py- What Happens:

- The script checks that at least one argument (

python3 some_script.py) is provided. - It reads

cases.txt(e.g., containing test inputs like pangrams). - It pipes these inputs to the command

time python3 some_script.py. - The

timecommand measures how longpython3 some_script.pytakes to process the inputs. - The output of

python3 some_script.py(plus thetimecommand’s timing statistics) is compared topangrams.txtusingdiff. - If the outputs match,

diffproduces no output (indicating success). If they differ,diffshows the differences, and the script fails (due toset -e).

- The script checks that at least one argument (

Why It Can Be Used for Speed Testing (Profiling)

The script facilitates speed testing in a Unix environment for the following reasons:

-

Use of

timeCommand:- The

timeutility measures the execution time of the provided command ($@), reporting metrics such as:- Real time: Total wall-clock time from start to finish.

- User time: CPU time spent in user mode.

- System time: CPU time spent in kernel mode.

- These metrics are included in the output, allowing the user to assess the performance of the command (e.g.,

python3 some_script.py).

- The

-

Input/Output Testing:

- The script feeds test inputs from

cases.txtto the command and compares the output topangrams.txt. This ensures that performance is measured while verifying correctness. - By testing with a standardized set of inputs, the script provides a consistent benchmark for comparing the speed of different implementations or optimizations.

- The script feeds test inputs from

-

Automation and Reusability:

- The script automates the process of running a command, measuring its time, and verifying its output. This is ideal for profiling multiple runs or comparing different programs (e.g., different Python scripts or algorithms).

- The use of

$@allows the script to work with any command, making it flexible for testing various executables or scripts.

-

Error Handling:

- The

set -euo pipefailandtrapensure that the script fails gracefully on errors or interruptions, making it reliable for repeated profiling runs. - If the command fails or produces incorrect output, the script exits with an error, alerting the user to issues that might affect performance measurements.

- The

-

Unix Environment Integration:

- The script leverages Unix tools (

time,diff,cat, process substitution) to create a lightweight, portable profiling setup without requiring specialized profiling software. - It fits naturally into a Unix workflow, where piping, redirection, and file-based input/output are common.

- The script leverages Unix tools (

How It Acts Like a Profiler

While not a full-fledged profiler (e.g., it doesn’t provide detailed function-level timing or memory usage like gprof or valgrind), the script serves as a simple performance testing tool by:

- Measuring Execution Time: The

timecommand provides high-level timing metrics, which are useful for comparing the overall performance of different programs or versions of a program. - Standardized Testing: By using fixed input (

cases.txt) and expected output (pangrams.txt), it ensures fair comparisons across runs. - Correctness Verification: The

diffcommand ensures that performance is measured only for correct outputs, preventing misleading results from faulty implementations. - Ease of Use: It simplifies the process of running timed tests, making it accessible for quick benchmarking during development or teaching.

Example Scenario

Suppose cases.txt contains a list of pangrams (sentences using every letter of the alphabet), and some_script.py is a Python script that processes these inputs (e.g., checks if they are pangrams). The script:

- Runs

python3 some_script.pywith inputs fromcases.txt. - Measures how long it takes using

time. - Compares the script’s output to

pangrams.txtto ensure correctness. - Outputs the

timestatistics (e.g.,real 0m0.123s,user 0m0.100s,sys 0m0.020s) alongside anydiffresults.

If you modify some_script.py (e.g., optimize the algorithm), you can re-run ./test.sh python3 some_script.py to compare the new timing results, effectively profiling the impact of your changes.

Limitations

- Coarse-Grained Profiling: The

timecommand provides only high-level metrics, not detailed insights into function calls or resource usage. - Single Run: The script runs the command once per invocation. For more accurate profiling, you’d need to run it multiple times and average the results (e.g., using a loop or external tools like

hyperfine). - Output Handling: The

timeoutput is included in thediff, which might cause issues ifpangrams.txtdoesn’t account for it. You may need to filter out timing stats for clean output comparison. - Input Dependency: The script assumes

cases.txtandpangrams.txtexist and are correctly formatted.

Improvements for Better Profiling

To enhance its profiling capabilities, you could:

-

Filter

timeOutput: Redirecttime’s stderr (where timing stats are printed) to a separate file or display it without affectingdiff.diff <(cat cases.txt | eval "$@" 2>/dev/null) pangrams.txt; time "$@" -

Multiple Runs: Wrap the command in a loop to average timings over multiple executions.

-

Use

hyperfine: Replacetimewith a tool likehyperfinefor more robust benchmarking with statistical analysis. -

Verbose Output: Add logging to display timing results explicitly, even if

diffsucceeds.

Conclusion

The script is a lightweight, Unix-style tool for running a command with test inputs, measuring its execution time, and verifying its output. It acts as a basic profiler by leveraging the time command to provide performance metrics and diff to ensure correctness. Its simplicity, combined with Unix’s powerful tooling, makes it effective for quick speed testing in a classroom or development context, particularly for comparing the performance of different scripts or algorithms in a Unix environment.

diff <( cat cases.txt| time python find_pangrams.py ) pangrams.txt python find_pangrams.py 0.07s user 0.02s system 100% cpu 0.094 total

./test.sh python3 find_pangrams.py

real 0m0.090s user 0m0.073s sys 0m0.016s

- the script is making a difference even it is a same command

I’ll explain the provided C code step-by-step, assuming you have no prior experience with C. The code is a program that reads lines from standard input (e.g., the terminal or a piped file) and checks if each line is a pangram (a sentence containing every letter of the alphabet). If a line is a pangram, it prints the line. Let’s break it down clearly and concisely, introducing C concepts as we go.

Overview of the Program

- Purpose: The program reads input lines, checks if each is a pangram using the

ispangramfunction, and prints the line if it is a pangram. It also handles errors and cleans up memory. - Key Components:

- A function

ispangram(incomplete) to check if a string is a pangram. - A

mainfunction that reads input lines and processes them.

- A function

- Input/Output:

- Input: Lines from standard input (e.g., typed in the terminal or piped from a file like

cases.txt). - Output: Prints pangram lines to standard output and an “ok” message to standard error when done.

- Input: Lines from standard input (e.g., typed in the terminal or piped from a file like

Code Breakdown

1. Header Files

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>- What are headers? In C,

#includeimports libraries (collections of functions and types) that your program needs. - Details:

<stdbool.h>: Provides thebooltype (trueorfalse). Without this, C doesn’t have a built-in boolean type (it uses integers:0for false, non-zero for true).<stdio.h>: Provides input/output functions likeprintf(print to console) andgetline(read input).<stdlib.h>: Provides memory management functions likemallocandfree, and other utilities likeexit.

2. The ispangram Function

bool ispangram(char *s) {

// TODO implement this!

return false;

}-

What it does: This function is supposed to check if a string

sis a pangram but is incomplete (it always returnsfalse). -

Key Concepts:

- Function Declaration:

bool: The return type, meaning the function returnstrueorfalse.ispangram: The function name.char *s: The parameter, a pointer to a string. In C, strings are arrays of characters (char), andchar *points to the first character.

- Strings in C: A string is an array of characters ending with a null character (

\0). For example, the string"hello"is stored as['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0']. - Placeholder Implementation: The

return falseis a stub, meaning the function isn’t implemented yet. A real implementation would check ifscontains all 26 letters (ignoring case, spaces, and punctuation).

- Function Declaration:

-

What a real

ispangrammight do:- Convert the string to lowercase.

- Track which letters (a–z) appear using a boolean array or bitmask.

- Ignore non-letter characters (spaces, numbers, punctuation).

- Return

trueif all 26 letters are present,falseotherwise.

3. The main Function

int main() {- What is

main?: Themainfunction is the entry point of a C program. When you run the program, execution starts here. - Return Type:

intmeansmainreturns an integer to the operating system (usually0for success, non-zero for errors). This code doesn’t explicitly return a value, which is okay in modern C (it assumesreturn 0).

size_t len;

ssize_t read;

char *line = NULL;- Variable Declarations:

size_t len:size_tis an unsigned integer type (e.g.,unsigned long) used for sizes (like string lengths). Here, it’s initialized to an undefined value (we’ll use it withgetline).ssize_t read:ssize_tis a signed integer type (e.g.,long) used for sizes or error codes. It stores the number of characters read bygetline.char *line = NULL:lineis a pointer to a string (initially set toNULL, meaning it points to nothing). It will hold each input line.

- Why

NULL?: In C, pointers must be initialized to avoid pointing to random memory.NULLindicates the pointer isn’t yet assigned.

while ((read = getline(&line, &len, stdin)) != -1) {-

Reading Input with

getline:getline(&line, &len, stdin): A function from<stdio.h>that reads a line fromstdin(standard input, e.g., keyboard or piped file).&line: Passes the address of thelinepointer.getlinemay allocate or reallocate memory forlineto store the input.&len: Passes the address oflen.getlinesetslento the size of the allocated buffer.stdin: A file stream representing standard input.

- Return Value:

getlinereturns the number of characters read (including the newline\n) or-1if it reaches the end of input (EOF) or an error occurs. - Assignment in Loop:

read = getline(...)stores the return value inread. - Loop Condition: The

whileloop continues as long asread != -1(i.e., there’s more input to read).

-

How

getlineWorks:- If

lineisNULLor the buffer is too small,getlineallocates or resizes memory forline. - It reads characters until it hits a newline (

\n) or EOF, storing the line inline(including the\n). - It updates

lento reflect the buffer size and returns the number of characters read.

- If

if (ispangram(line))

printf("%s", line);- Processing Each Line:

ispangram(line): Calls theispangramfunction with the current line. Sinceispangramis incomplete, it always returnsfalse, so nothing is printed yet.printf("%s", line): Ifispangramreturnstrue, this prints the line to standard output (stdout). The%sformat specifier is for strings.- Note: The line includes the trailing

\n(fromgetline), soprintfpreserves it, ensuring each pangram is printed on a new line.

if (ferror(stdin))

fprintf(stderr, "Error reading from stdin");- Error Checking:

ferror(stdin): Checks if an error occurred while reading fromstdin(e.g., a file read error).fprintf(stderr, ...): Prints an error message to standard error (stderr), a separate output stream for errors (distinct fromstdout).- Why

stderr?: Errors are sent tostderrso they can be separated from normal output (e.g., when redirecting output to a file).

free(line);- Memory Cleanup:

free(line): Deallocates the memory allocated bygetlineforline. In C, you must manually free dynamically allocated memory to avoid memory leaks.- Why needed?:

getlineallocates memory forline(ifNULLor too small). Failing to free it would leak memory.

fprintf(stderr, "ok\n");- Final Message: Prints “ok” (with a newline) to

stderrto indicate the program completed. - Why

stderr?: Likely to separate status messages from the actual output (pangrams), which go tostdout.

How It Fits with the Bash Script

From your previous question, the Bash script (test.sh) runs this program with input from cases.txt and compares its output to pangrams.txt. Here’s how they connect:

- Input: The Bash script pipes

cases.txt(e.g., a list of test strings) to the C program’sstdin. - Processing: The C program reads each line, checks if it’s a pangram (once

ispangramis implemented), and prints pangram lines tostdout. - Output Comparison: The Bash script uses

diffto compare the C program’s output (pangram lines) topangrams.txtto verify correctness. - Timing: The Bash script’s

timecommand measures how long the C program takes, useful for profiling.

For example, if cases.txt contains:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

Hello world

A pangram is fun

And pangrams.txt contains only the pangram:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

The C program (with a working ispangram) would print only the first line, and diff would check if it matches pangrams.txt.

Key C Concepts for Beginners

Here’s a quick primer on C concepts in this code, since you’re new to C:

-

Pointers (

*):- A pointer is a variable that stores a memory address.

char *linepoints to a string’s first character. &variablegets the address of a variable, used to modifylineandleningetline.

- A pointer is a variable that stores a memory address.

-

Memory Management:

- C doesn’t have automatic garbage collection. You allocate memory (e.g.,

getlinedoes this) and must free it withfree. - Failing to

freecauses memory leaks.

- C doesn’t have automatic garbage collection. You allocate memory (e.g.,

-

Standard Input/Output:

stdin: Where input comes from (keyboard, file, or pipe).stdout: Where normal output goes (console or file).stderr: For error messages or status.

-

Strings:

- Strings are

chararrays ending with\0. - Functions like

printfandgetlinehandle strings viachar *.

- Strings are

-

Types:

size_t: Unsigned integer for sizes (e.g., buffer lengths).ssize_t: Signed integer for sizes or error codes (e.g.,getline’s return).bool: Boolean type (trueorfalse) from<stdbool.h>.

Example: Completing ispangram

Since ispangram is incomplete, here’s a simple implementation to make the program functional:

bool ispangram(char *s) {

bool letters[26] = {false}; // Track a-z

for (int i = 0; s[i] != '\0'; i++) {

char c = s[i];

// Convert to lowercase and check if it's a letter

if (c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z') c = c + ('a' - 'A');

if (c >= 'a' && c <= 'z') {

letters[c - 'a'] = true; // Mark letter as seen

}

}

// Check if all letters are present

for (int i = 0; i < 26; i++) {

if (!letters[i]) return false;

}

return true;

}- How it works:

- Creates a boolean array to track letters a–z.

- Iterates through the string

s. - Converts uppercase to lowercase (e.g.,

'A'to'a') and ignores non-letters. - Marks each letter’s index (e.g.,

'a'→ index 0,'b'→ index 1) astrue. - Returns

trueonly if all 26 letters were seen.

Running the Program

-

Compile: Save the code as

pangram.cand compile it withgcc:gcc -o pangram pangram.cThis creates an executable named

pangram. -

Run Manually:

./pangramType lines (e.g., “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog”), and press Ctrl+D (EOF) when done. Pangrams will be printed.

-

With the Bash Script: If

cases.txtexists, run:./test.sh ./pangramThis pipes

cases.txtto the program, times it, and compares output topangrams.txt.

Sample Run

Input (cases.txt):

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

Hello world

With ispangram implemented:

- The program reads each line.

- Checks if it’s a pangram (only the first line is).

- Prints:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog - Prints to

stderr:ok

Bash Script Output:

- If

pangrams.txtmatches the output,diffshows nothing (success). timeshows execution time (e.g.,real 0m0.010s).

Why This Code?

This code is likely part of a programming assignment (as hinted by your teacher’s Bash script). It teaches:

- Reading input in C (

getline). - String processing (

ispangram). - Memory management (

free). - Error handling (

ferror). - Integration with Unix tools (via

stdin/stdout).

Next Steps

- Try Implementing

ispangram: Use the example above or experiment with your own logic. - Test It: Create a

cases.txtwith pangrams and non-pangrams, and use the Bash script to test. - Learn More C:

- Practice with pointers (

*,&). - Explore string functions in

<string.h>(e.g.,strlen,strtolower). - Read about

getlineand dynamic memory in C.

- Practice with pointers (

If you have questions about specific parts or want help with ispangram, let me know!

the different C compiler , gcc vs clang

-

Compiler Explorer can show clang and gcc result at the same time

-

The Architecture of Open Source Applications (Volume 1)LLVM AOSA book

llvm got more reusable tools

rust → write a front end llvm → easy to use and build cross different os env

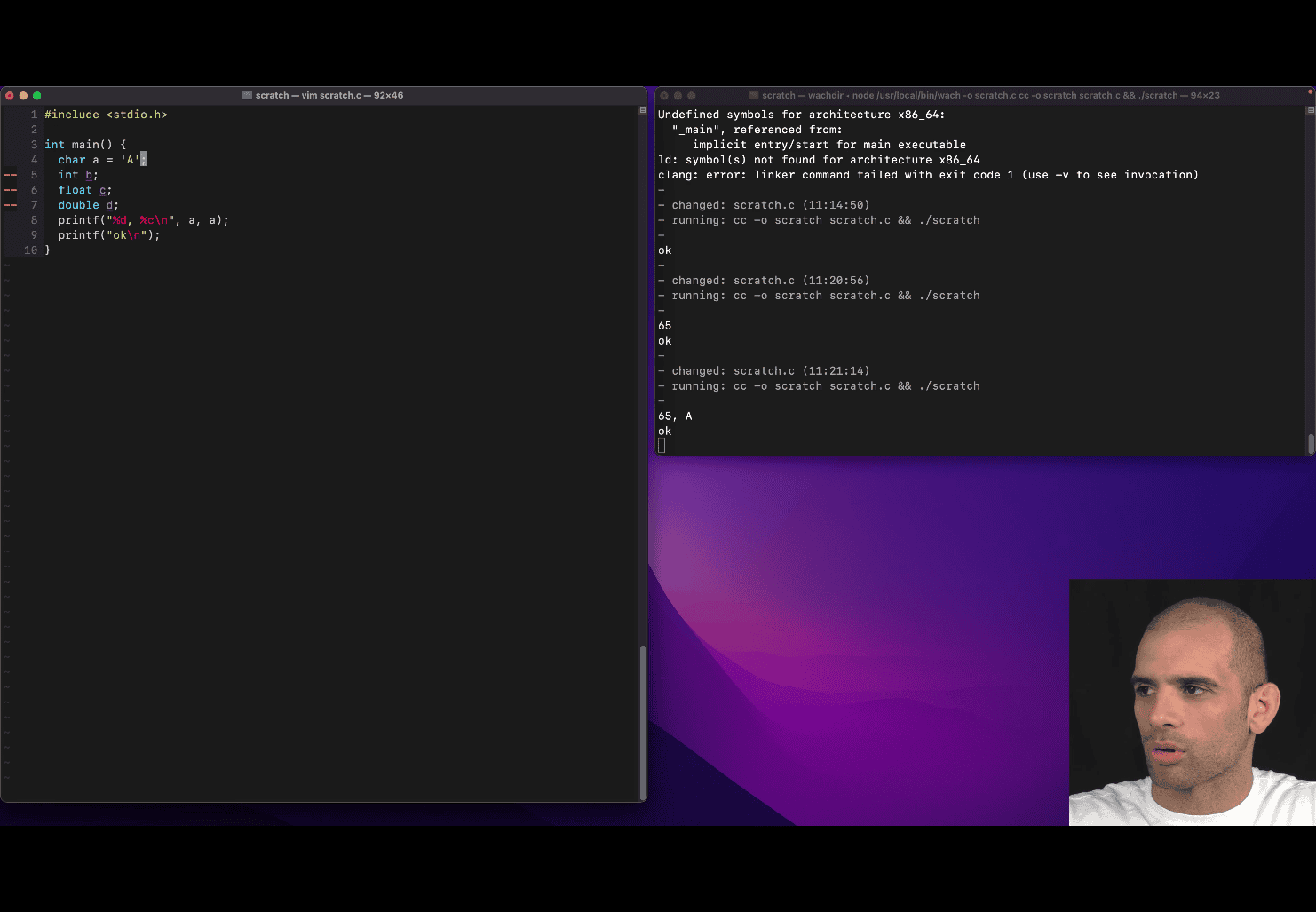

Type definitions and literals in C

include <stdio.h> printf (“%d, %c\n”, a, a) ; → this print the same a in different format c → character

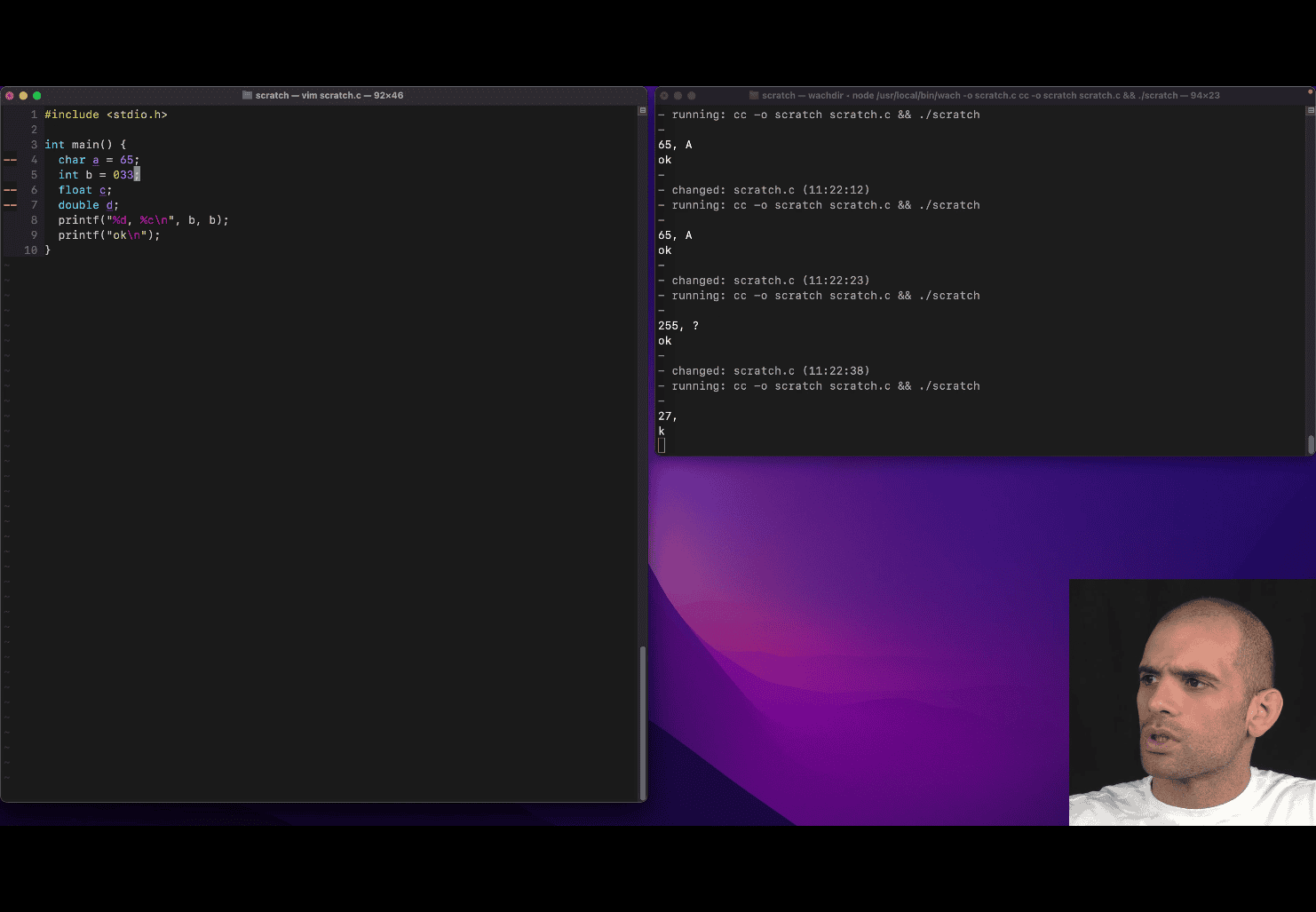

int b 033; → octal

can’t do 0b11 in c , but compiler will do that for you

int b 033; → octal

can’t do 0b11 in c , but compiler will do that for you

“%f\n”, c (float, 0.3)

long int e = 20L; (“L”→ imply this is a L (long) )

long e = 20L; (skip the “int” if using L)

short int f = 5; short f = 5; (still make sure)

long and short is mechine related

short < = to int

int < = to long

The number of bits used by a normal int type in C is not fixed by the standard but has a required minimum size and commonly used sizes depending on the platform.

- Minimum size: The C standard specifies that

intmust be at least 16 bits 2 bytes[2][5][6]. - Common actual sizes: On most modern systems,

intis typically 32 bits (4 bytes), but it can also be 16 bits on some older or embedded systems[2][3][4][5][6]. - Platform-dependent: The exact size of

intdepends on the compiler and the hardware architecture. To find the size on your specific system, you can use thesizeof(int)operator in C code[2][5].

Summary Table

| Type | Minimum bits (C standard) | Common sizes |

|---|---|---|

| int | 16 | 16 or 32 |

Key points:

intmust be at least 16 bits, but is usually 32 bits on modern computers[1][2][4][5][6].- The size is chosen to match what is most efficient for the target processor[1].

- Always check with

sizeof(int)if you need to know the exact size on your platform[2][5].

Example C code to check size:

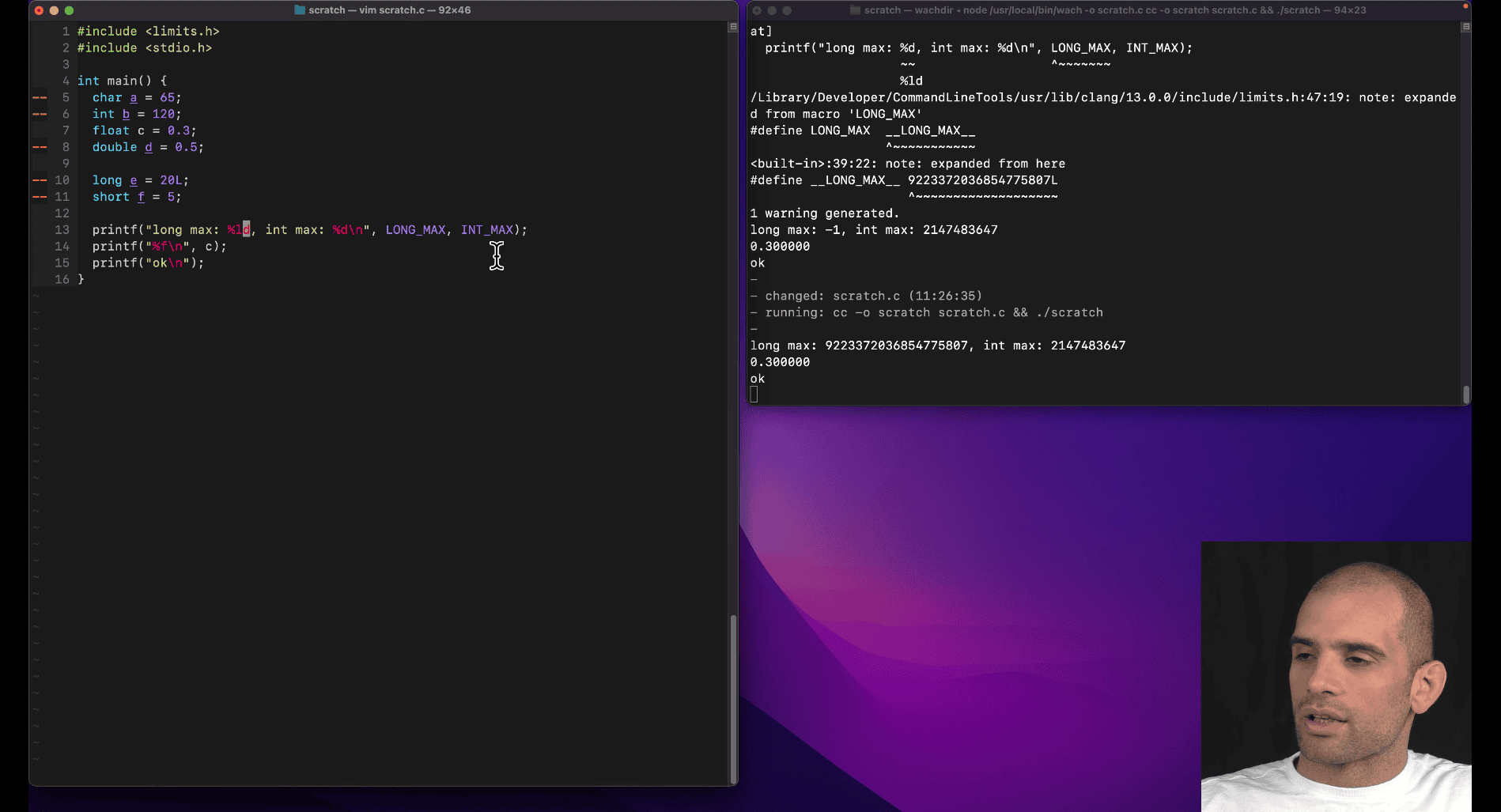

printf("int is %zu bytes\n", sizeof(int));In summary, a normal int in C is at least 16 bits, but is most commonly 32 bits on contemporary systems

%ld → long digit, %d → max int

include <limits.h> → show the limits

%ld → long digit, %d → max int

include <limits.h> → show the limits

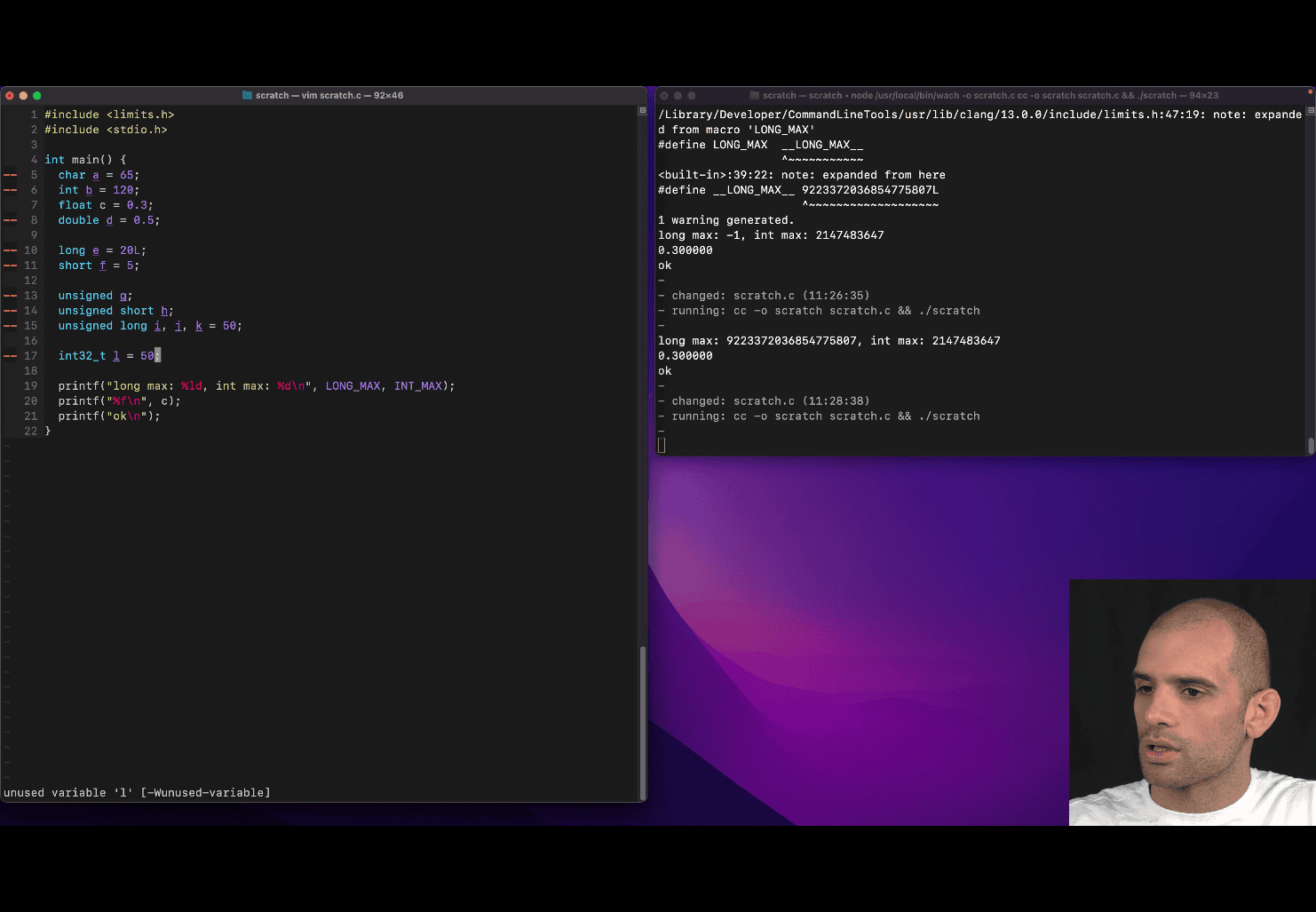

unsigned g ; and givin bits to variable

include <stdint.h>

int32_t l = 50;

Key Features of <stdint.h>

-

Fixed-Width Integer Types

Provides types like

int8_t,int16_t,int32_t,int64_t(signed) anduint8_t,uint16_t,uint32_t,uint64_t(unsigned).These types guarantee the exact number of bits, regardless of the platform.

-

Minimum and Fastest Integer Types

Defines types like

int_least8_t,int_least16_t, etc., which guarantee at least the specified width.Defines types like

int_fast8_t,int_fast16_t, etc., which are the fastest types with at least the specified width. -

Maximum Integer Types

intmax_tanduintmax_trepresent the largest signed and unsigned integer types supported by the implementation. -

Macros for Limits

Macros such as

INT32_MAX,UINT8_MAX, etc., provide the maximum and minimum values for each type.

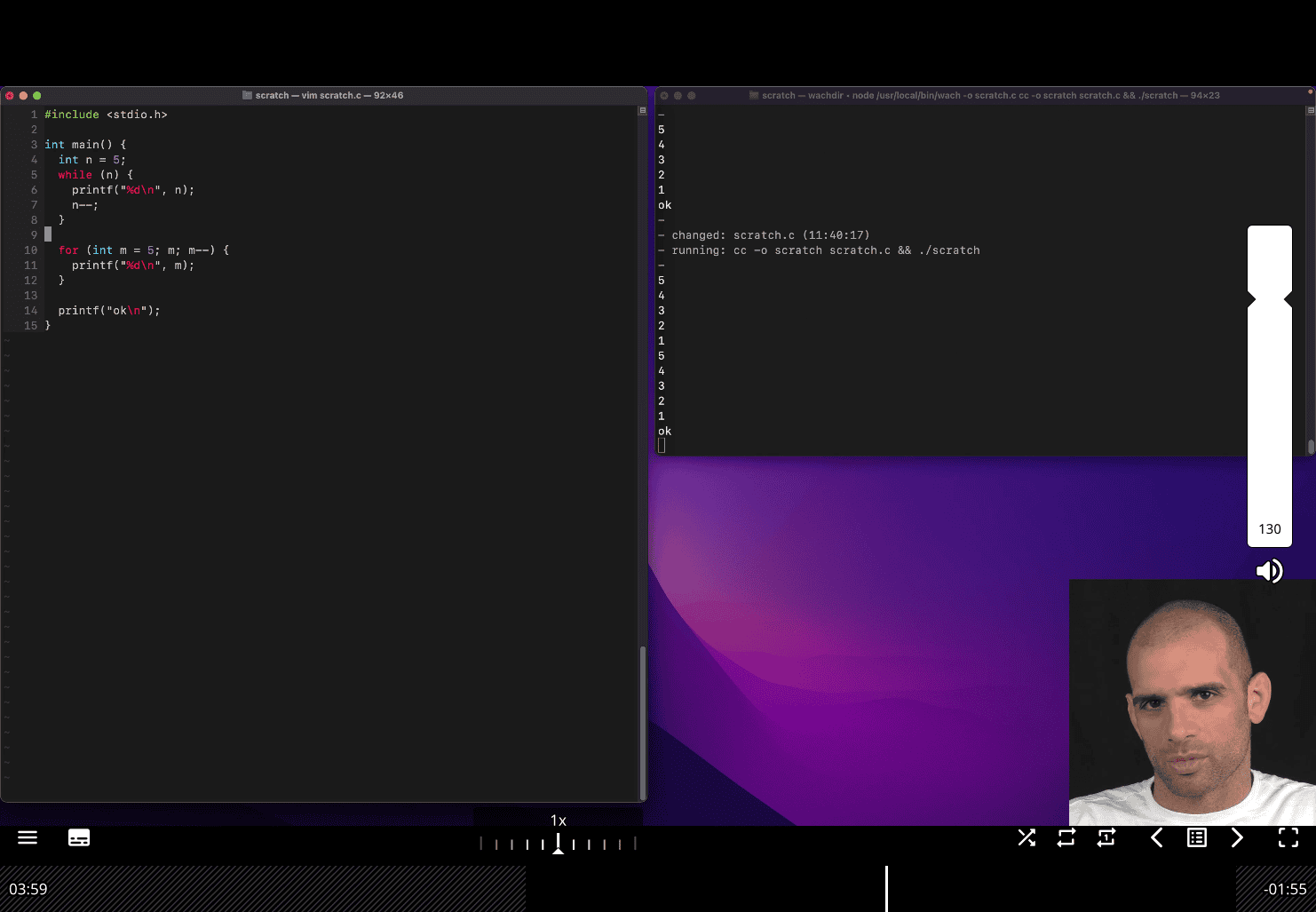

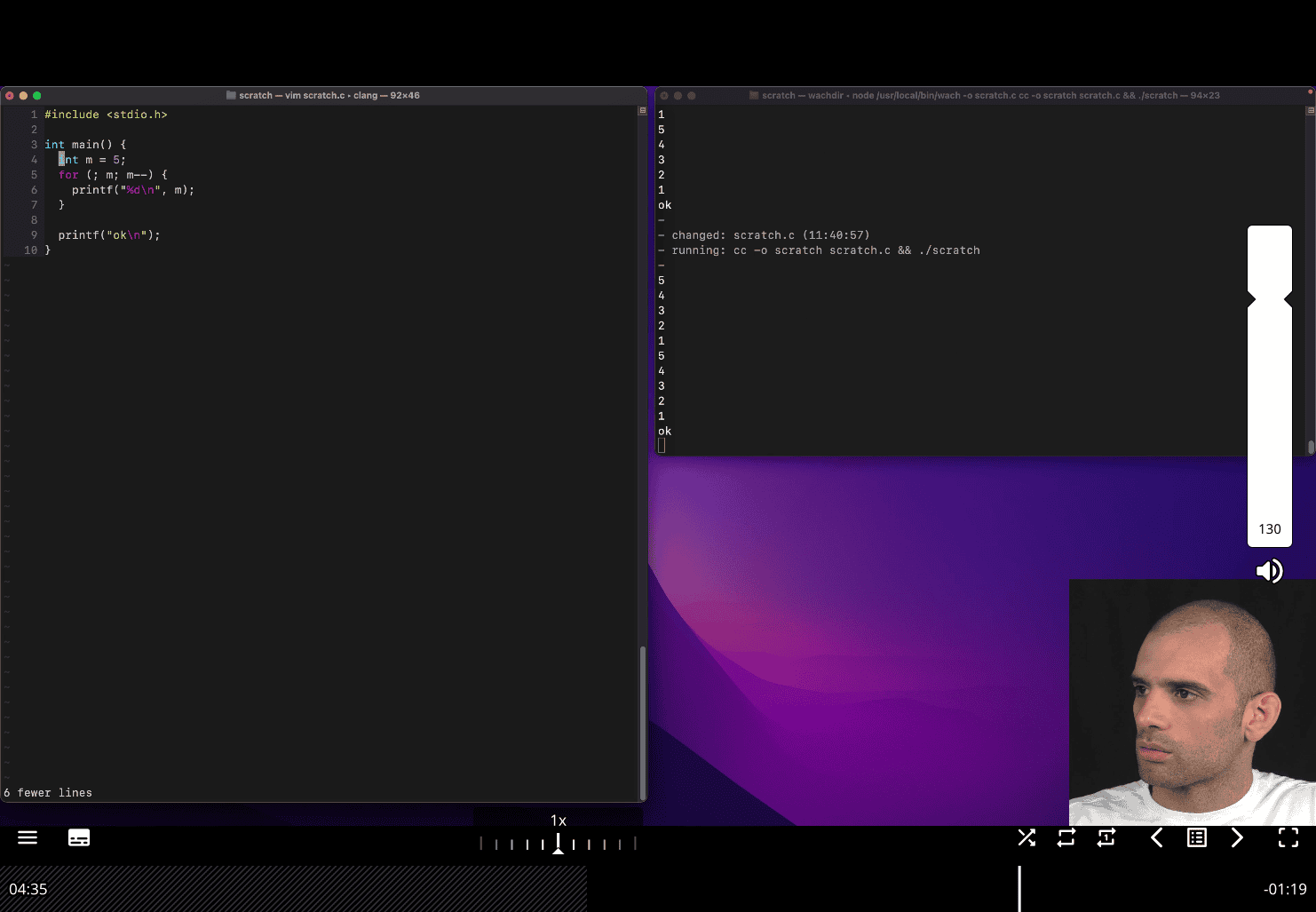

Loop syntax in C

// int n = 5;

for (int m = 5; m > 0; m--) {

printf("%d\n", m);

}is same as

for (int m = 5; m; m--) {

same logic → all place in one place then use for loop

you don have to initate in the for loop statment s

for loop in while like:

for (;;){

}

for (;m;;){}

for(;;){}→while (1){}

do while (in end )

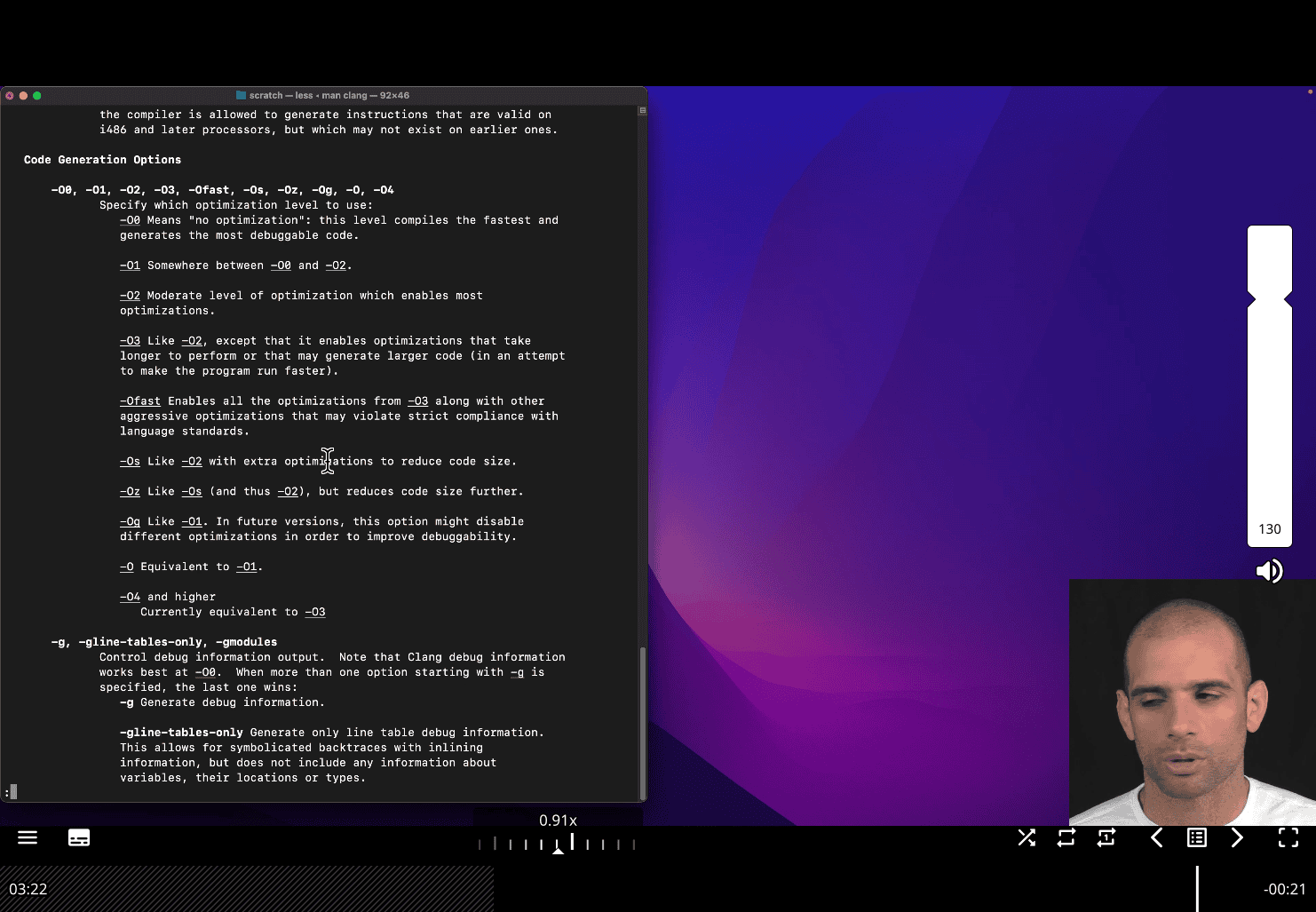

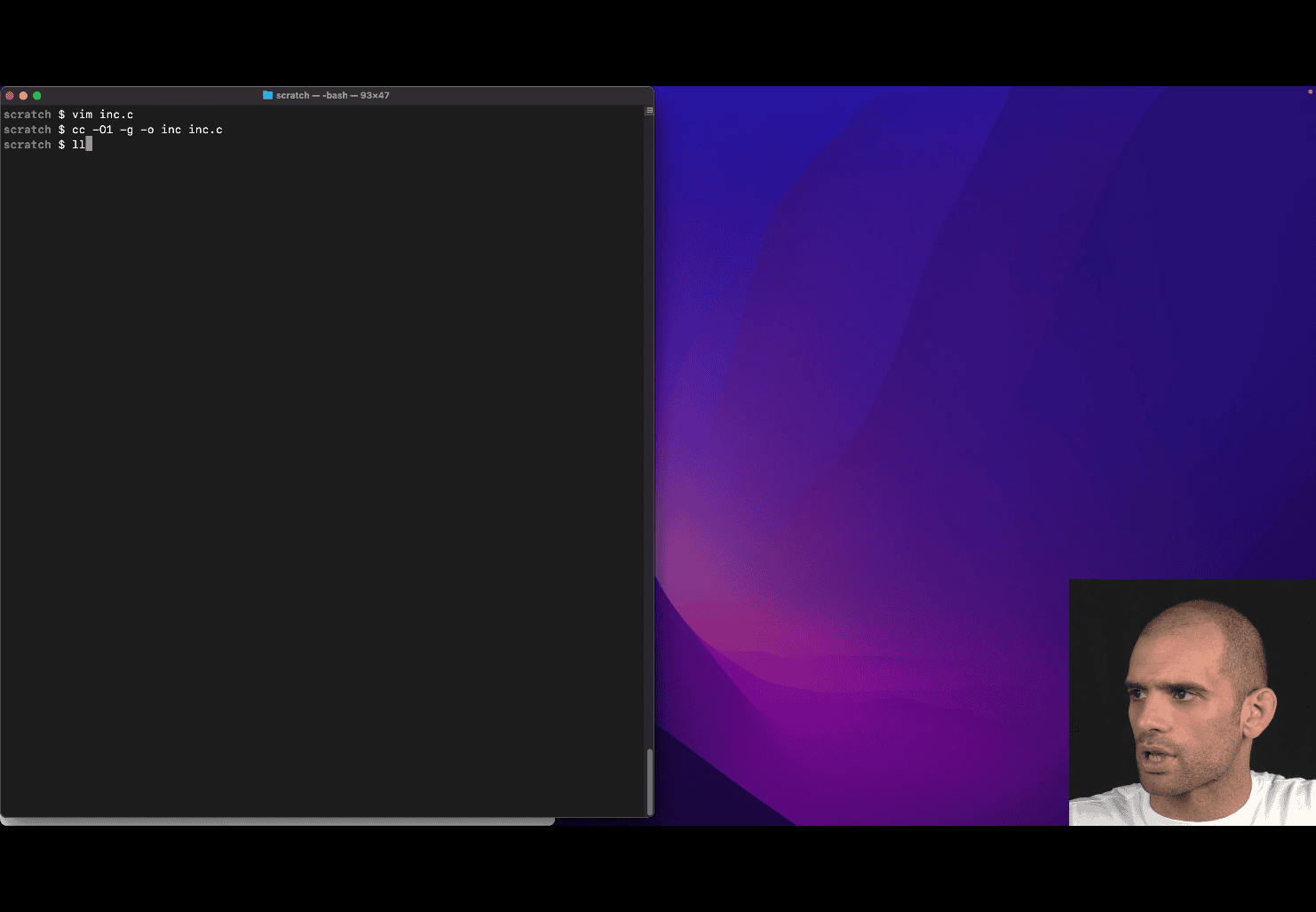

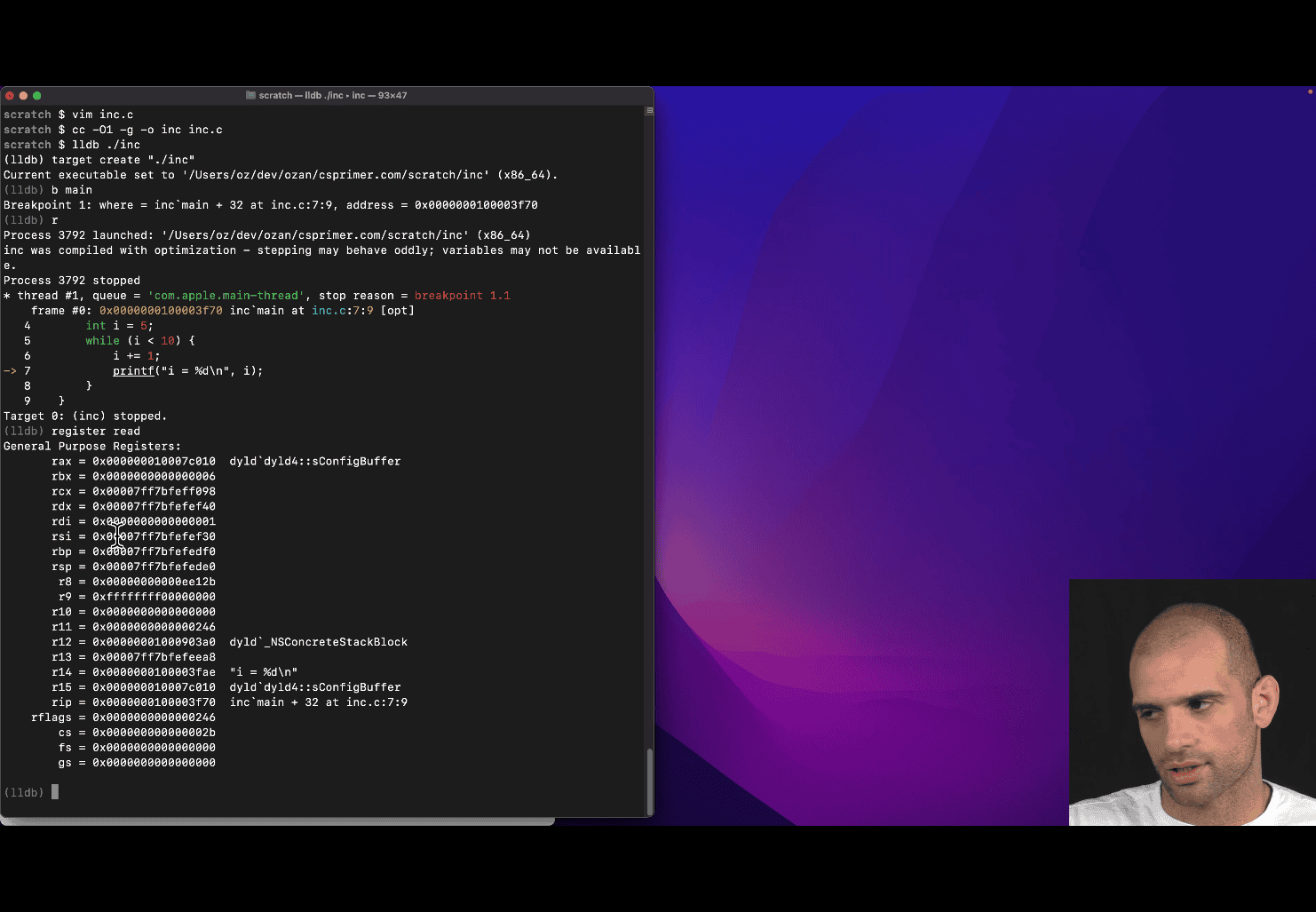

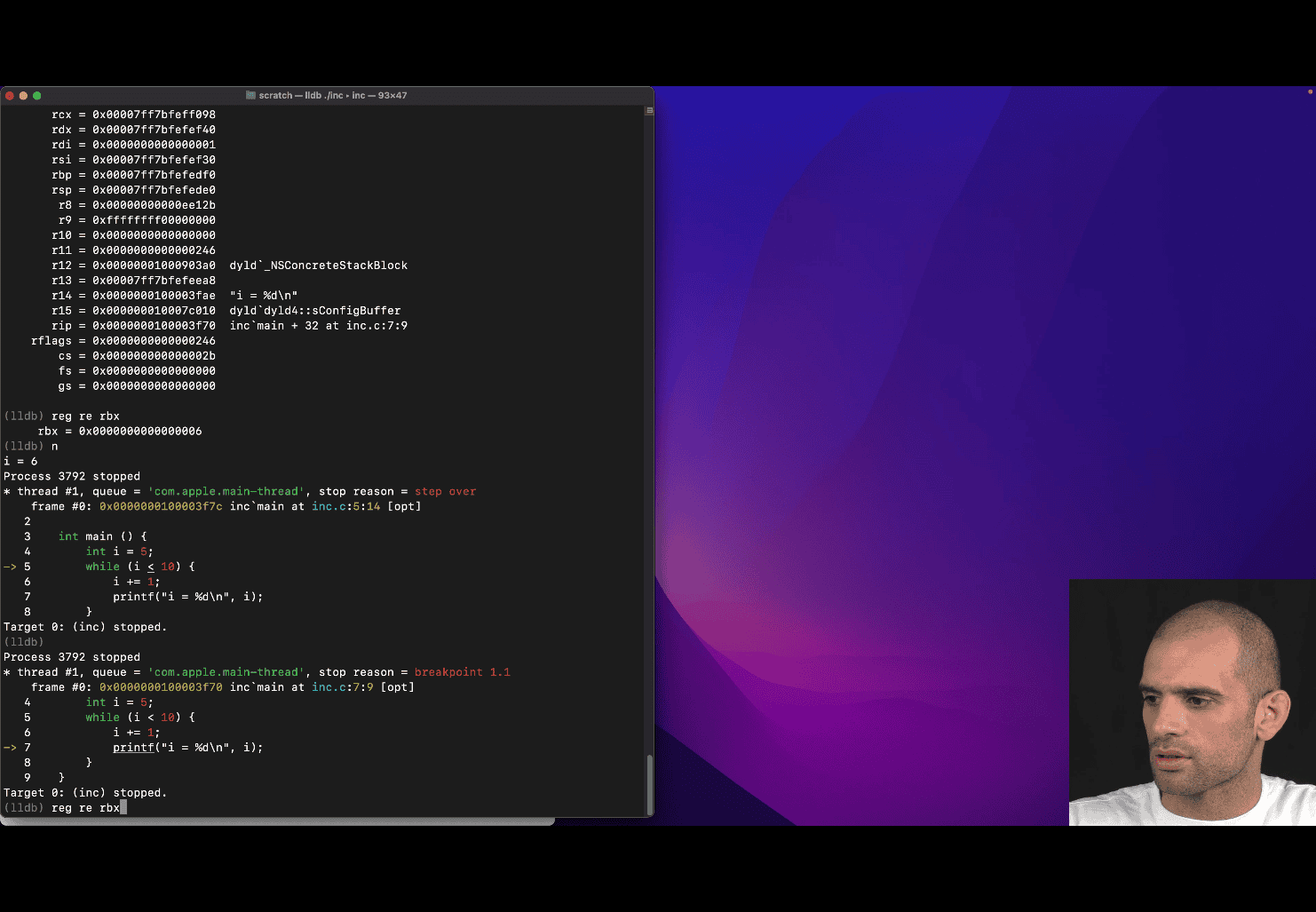

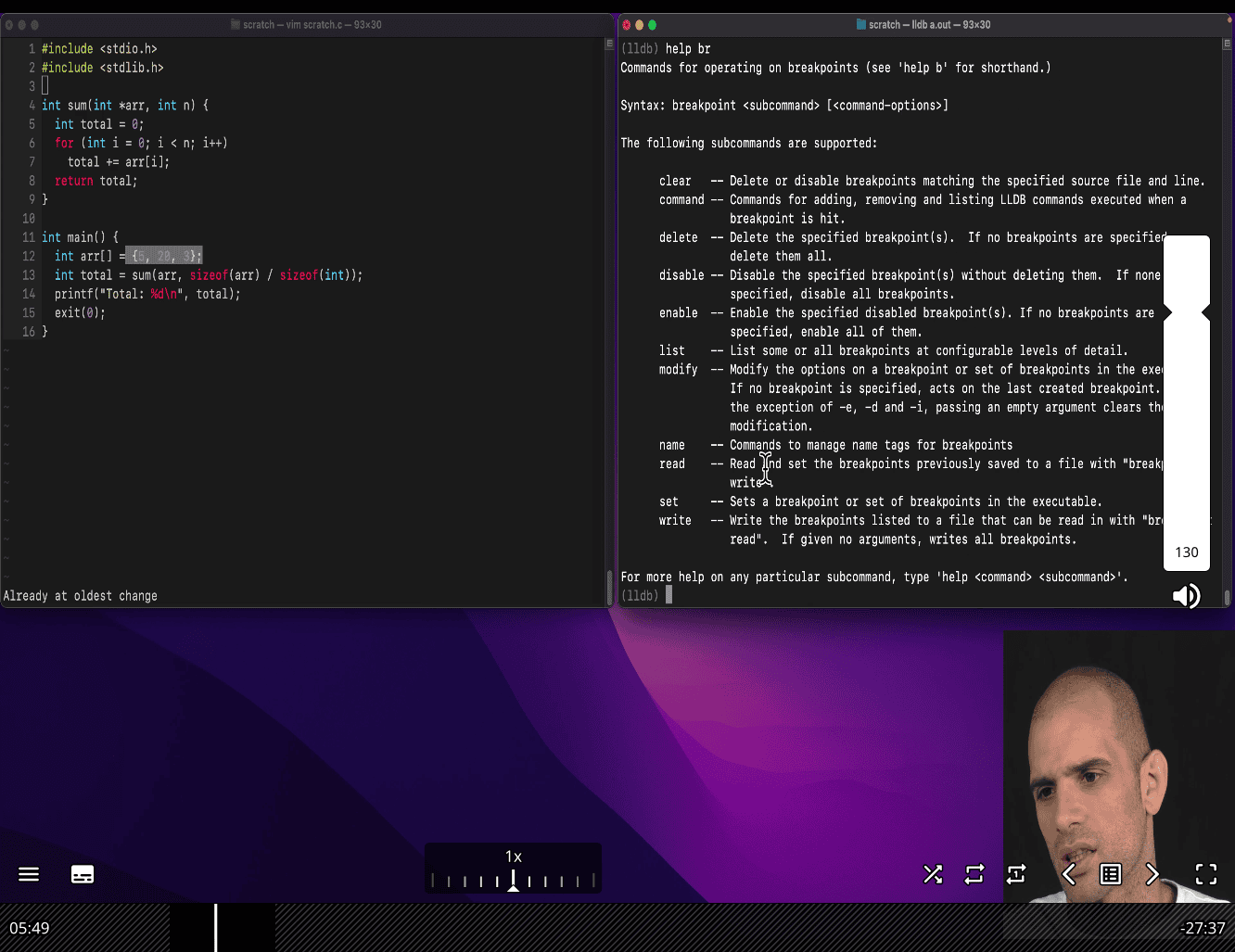

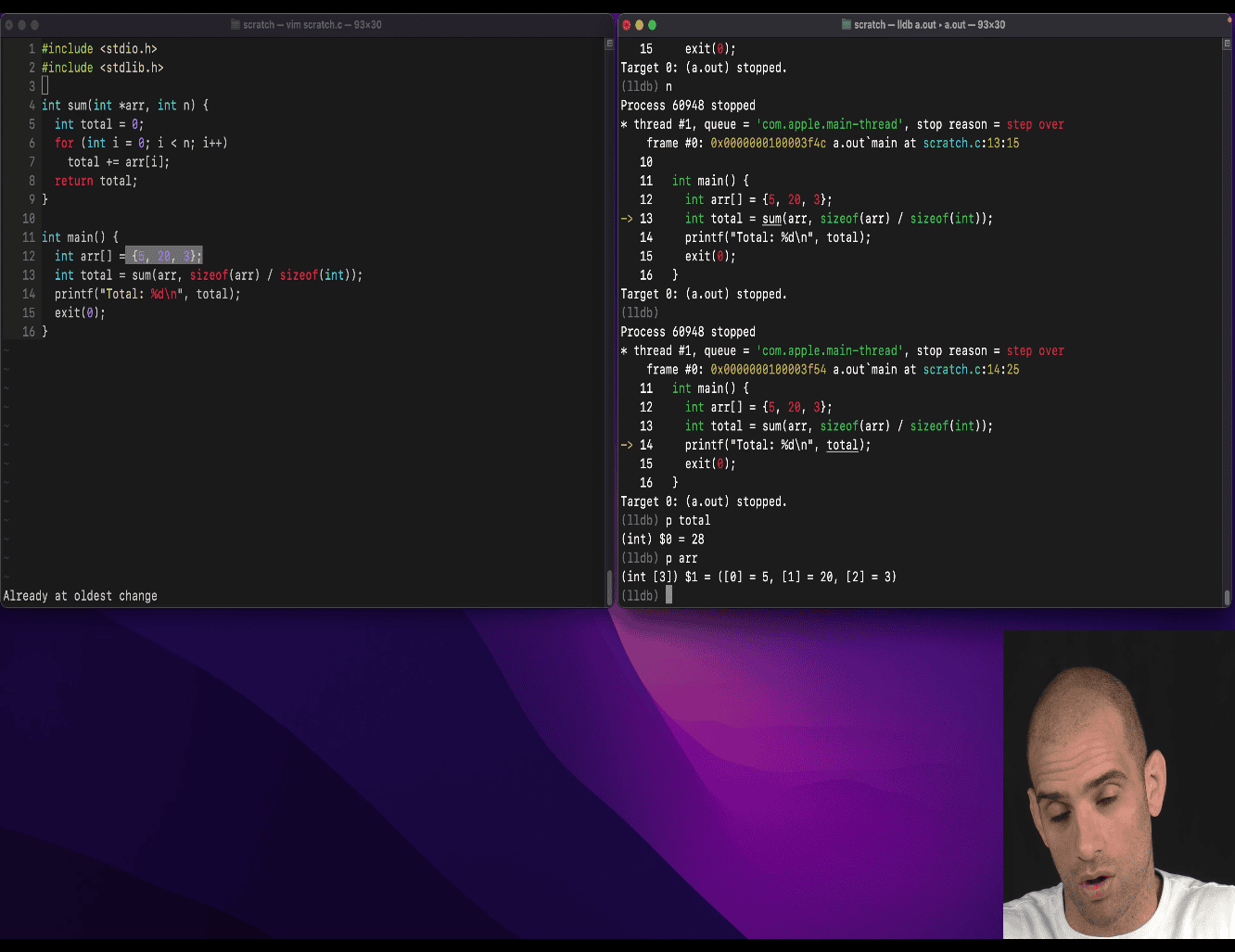

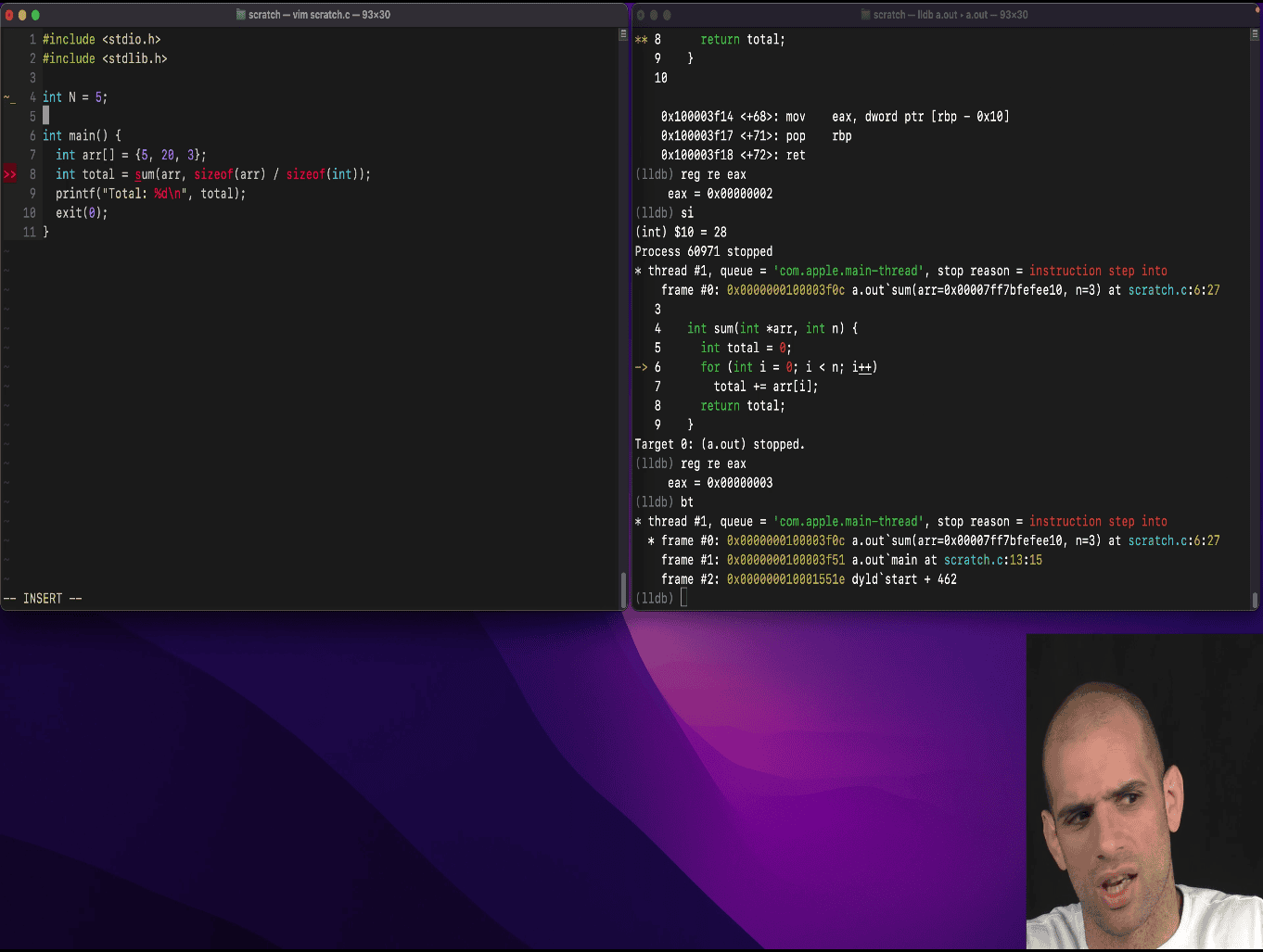

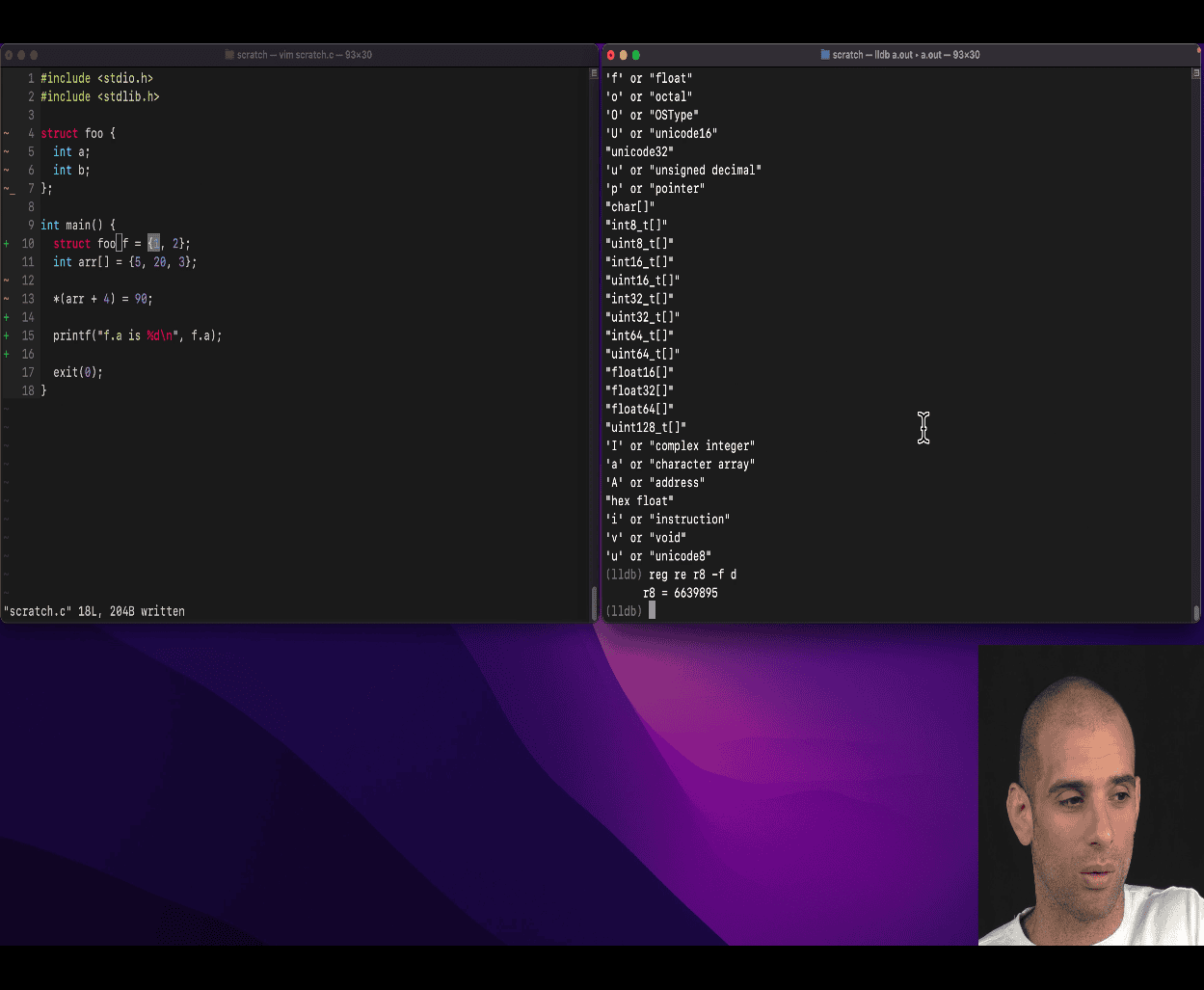

- What is the effect of the compiler optimization level flag?

- sometime you may prefer other one , for debugging and readability e.g O1 maybe

e.g in unix , you don’t want run all the optimization and just use the thing in the development

- What is a register?

cc -O1 -g -o inc inc.c using lldb ./inc

rbx → compiler chosen to store the value of “i”

reg re → short form of register read

reg re rbx

and apply format function to help reading

this is useful skill to check what is going on register, and register is run faster than ram

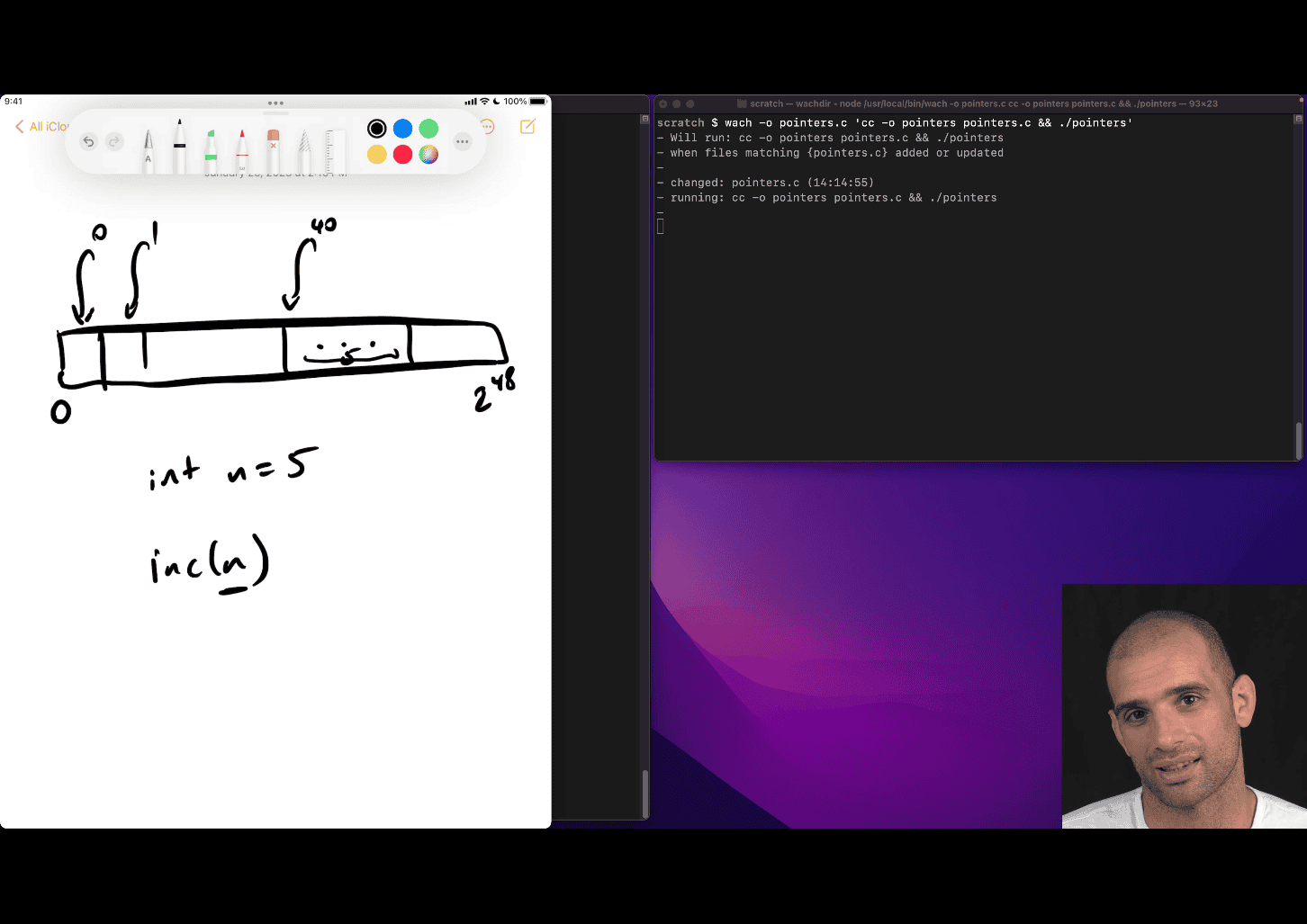

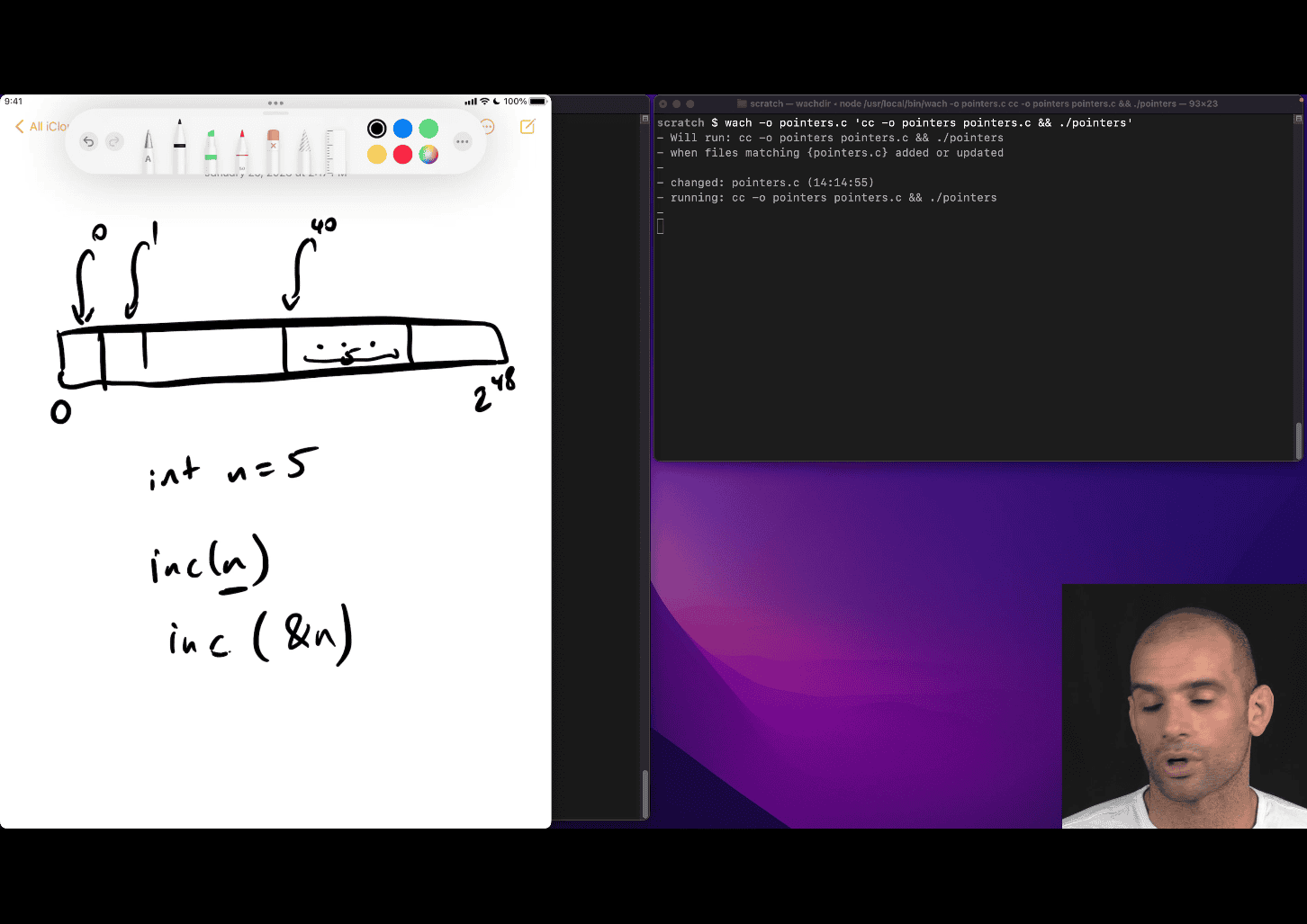

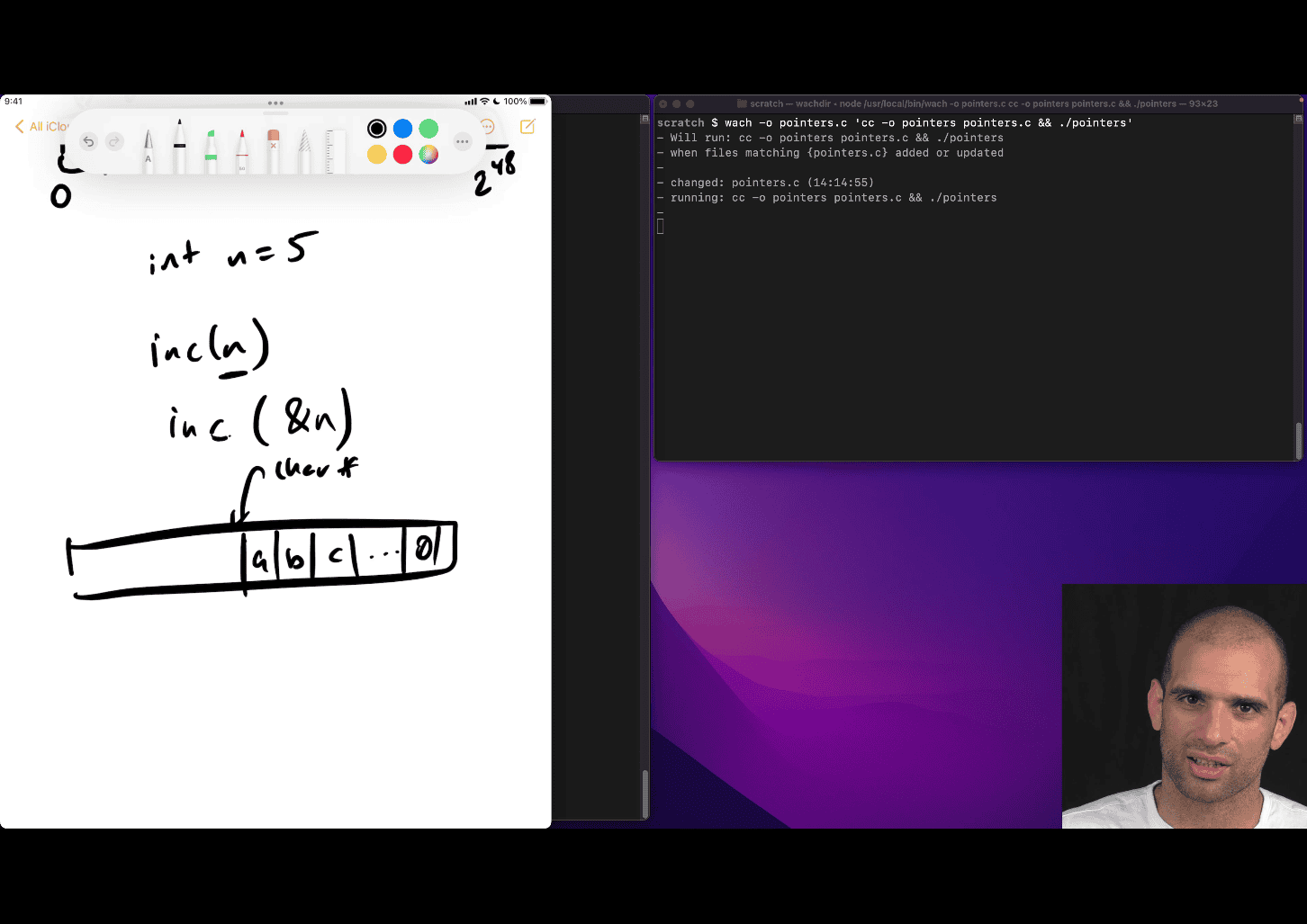

- Overview of pointers and arrays in C

- need to pass the address to really change the value in that n = value location

inc (&n)

location is 40 in that cases

location is 40 in that cases

char * → inc(the address) then get a , inc one more → b

last 0 → imply it is the end

other reason, two return value e.g. need address

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int n = 5;

printf("*n = %d, &n = %p\n", n, (void*)&n);

return 0;

}#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int n = 5;

int *p = &n;

// printf("n = %d, &n = %p\n", n, (void *)&n);

printf("n = %d, &n = %p\n", n, p);

}

-

same thing ,

*pis just reminder as int pointer, more likeint* p -

int foo = *p;→ * is a pointer , follow the pointer p → get the value→ that’s foo (Dereferencing) -

Dereferencing

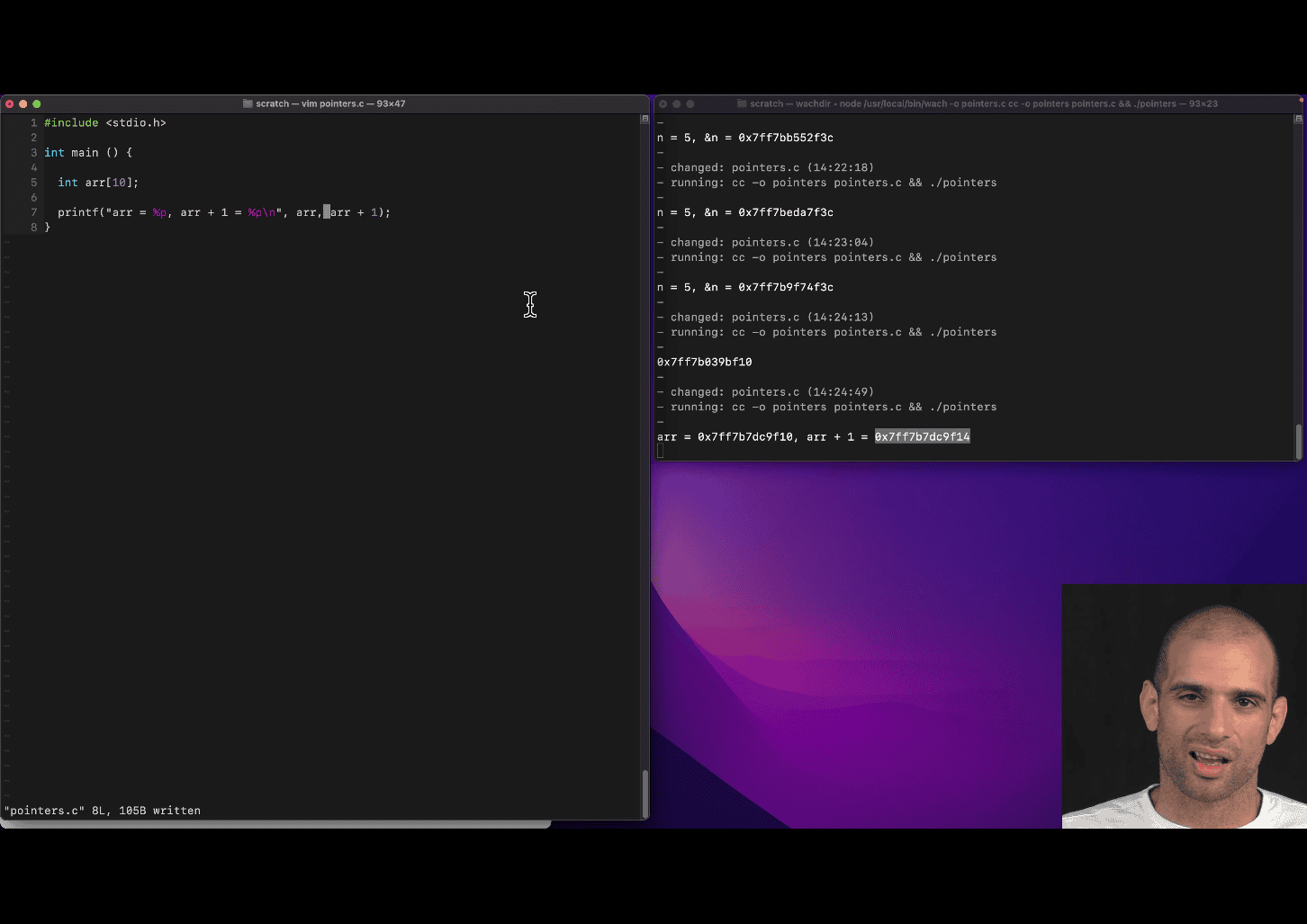

array are syntax for pointer

array → starting location of a thing, need type etc

int arr[10];

printf("%p",arr) %p → pointer

take the pointer of arr[3]→ return 42

deference ⇒ *()

- deference ⇒

*()

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[16];

arr[3] = 42;

printf("*arr + 3 = %p, *(arr + 3) = %d\n", arr + 3, *(arr + 3));

return 0;

}Your teacher is introducing you to the concept of pointers in C and how array indexing relates to pointer arithmetic. Let’s break down the key idea behind arr[3] being equivalent to *(arr + 3).

1. Arrays and Pointers in C

In C, an array (like int arr[16]) is closely related to pointers. When you declare an array, the name arr represents the base address of the array, which is the memory address of the first element (arr[0]). This means arr is effectively a pointer to the starting point of the array in memory.

Each element in the array is stored in contiguous memory locations, and the size of each element depends on the data type (e.g., int is typically 4 bytes on most systems).

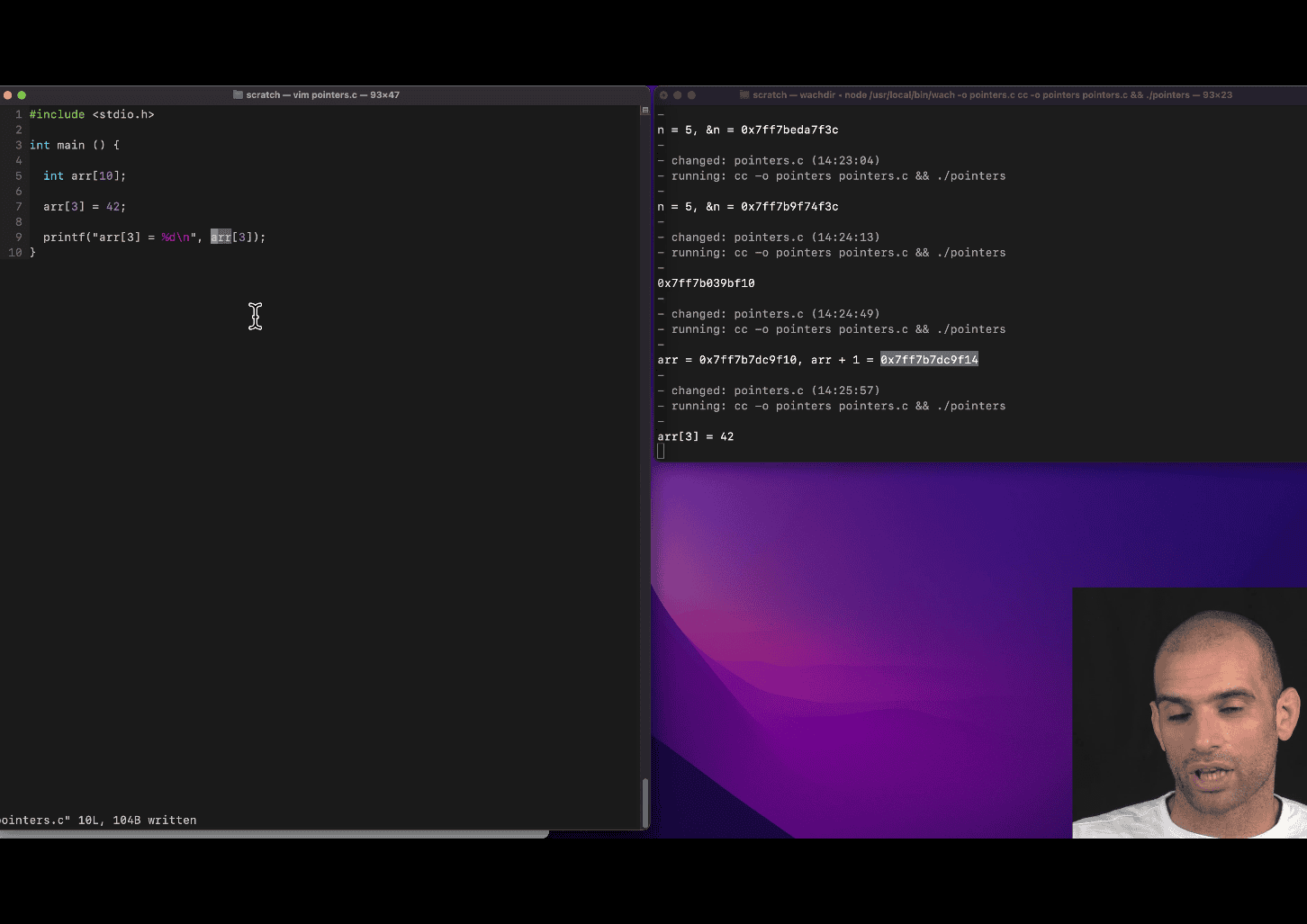

2. Array Indexing: arr[3]

When you write arr[3], you’re accessing the element at index 3 of the array. This is a convenient syntax for accessing elements, but under the hood, C uses pointer arithmetic to locate the memory address of arr[3].

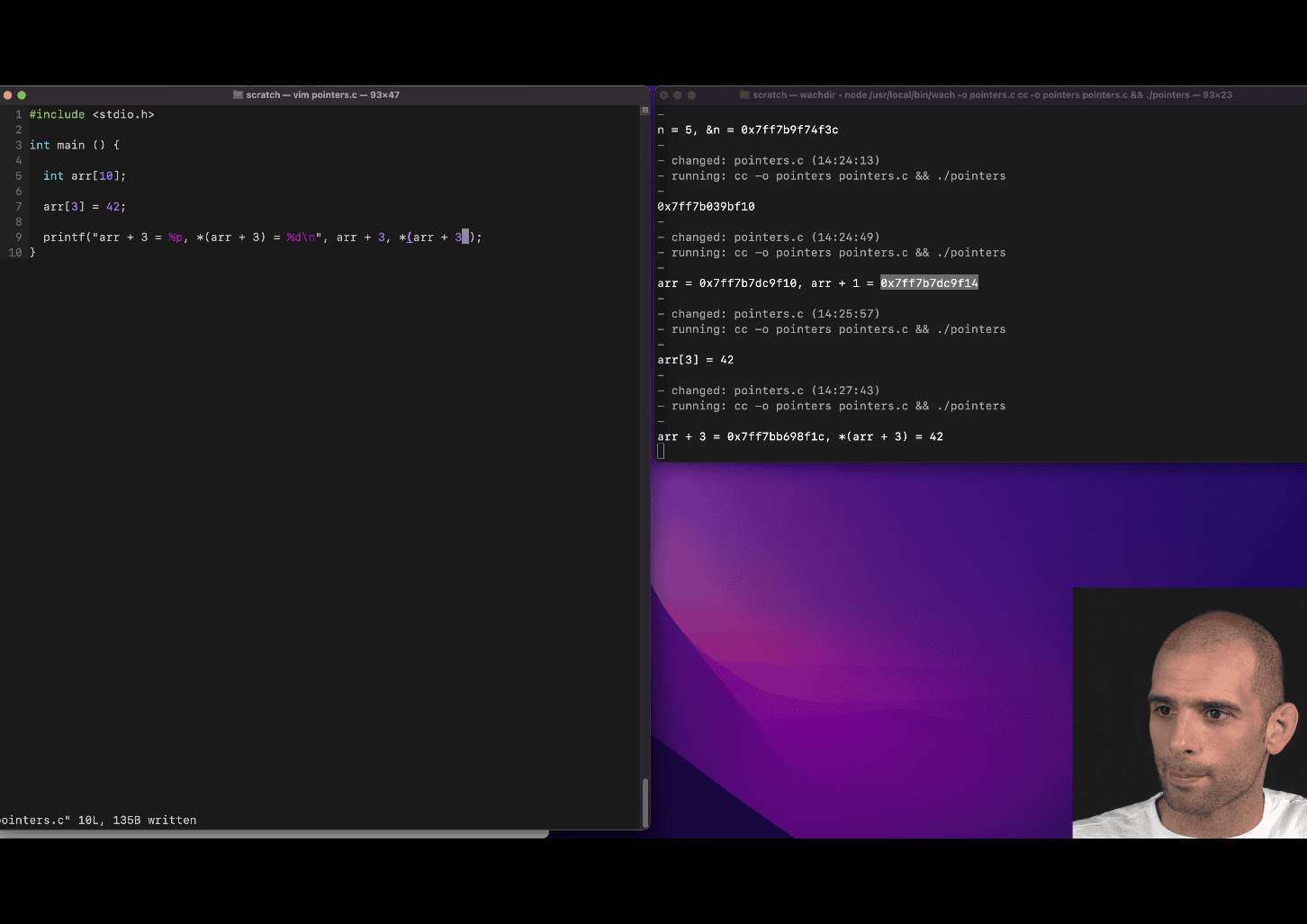

3. Pointer Arithmetic: *(arr + 3)

The expression *(arr + 3) is the pointer-based equivalent of arr[3]. Let’s break it down:

arris the base address of the array (a pointer toarr[0]).arr + 3performs pointer arithmetic. It calculates the memory address of the element that is 3 positions beyond the base address. Since eachinttakes up a fixed number of bytes (e.g., 4 bytes),arr + 3points to the address ofarr[3].- The

*operator dereferences the pointer, meaning it retrieves the value stored at the addressarr + 3. So,*(arr + 3)gives you the value ofarr[3].

4. Why arr[3] == *(arr + 3)?

In C, the array indexing syntax arr[i] is syntactic sugar for *(arr + i). This means:

arr[3]is exactly the same as*(arr + 3).- Both expressions compute the address of the element at index 3 and retrieve its value.

This equivalence exists because arrays are implemented as pointers in C, and the indexing operation is just a shorthand for pointer arithmetic and dereferencing.

5. Example from Your Code

In your code:

int arr[16];

arr[3] = 42;

printf("*arr + 3 = %p, *(arr + 3) = %d\n", arr + 3, *(arr + 3));arr + 3computes the memory address ofarr[3]. The%pformat specifier prints this address (e.g., some hexadecimal value like0x7ffee4a0c0c).*(arr + 3)dereferences that address to get the value stored there, which is42(since you setarr[3] = 42). The%dformat specifier prints this value.

6. What Your Teacher Is Teaching

Your teacher is emphasizing that:

- Arrays and pointers are deeply connected in C.

- Array indexing (

arr[i]) is just a convenient way to perform pointer arithmetic (*(arr + i)). - Understanding pointer arithmetic is key to mastering pointers, as it shows how C navigates memory to access array elements.

- By using

*(arr + 3), you’re directly manipulating memory addresses, which is what C is doing behind the scenes when you writearr[3].

7. Key Takeaways

arr[3]and*(arr + 3)are equivalent ways to access the same element.arr + 3gives you the address ofarr[3].*(arr + 3)dereferences that address to get the value (e.g.,42).- This concept is fundamental to understanding pointers, memory management, and how arrays work in C.

8. A Visual Explanation

Imagine the array arr in memory (assuming int is 4 bytes):

Index: arr[0] arr[1] arr[2] arr[3] ...

Address: 1000 1004 1008 1012 ...

Value: ? ? ? 42 ...

arrpoints to address1000(base address).arr + 3points to address1012(base + 3 * sizeof(int)).*(arr + 3)retrieves the value at address1012, which is42.arr[3]does the same thing but with simpler syntax.

9. Practice to Reinforce

To solidify this, try experimenting with your code:

- Print

arr[3]and*(arr + 3)to confirm they’re identical. - Print the addresses

&arr[3]and(arr + 3)to see they point to the same location. - Try accessing other indices (e.g.,

arr[5]vs.*(arr + 5)) to build intuition.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[16];

arr[3] = 42;

arr[5] = 99;

printf("arr[3] = %d\n", arr[3]);

printf("*(arr + 3) = %d\n", *(arr + 3));

printf("pointer of arr3 = %p\n", &arr);

printf("&arr[3] = %p\n", (void *)&arr[3]);

printf("arr + 3 = %p\n", (void *)(arr + 3));

printf("arr[5] = %d\n", arr[5]);

printf("*(arr + 5) = %d\n", *(arr + 5));

printf("pointer of arr5 = %p\n", &arr);

printf("&arr[5] = %p\n", (void *)&arr[5]);

printf("arr + 5 = %p\n", (void *)(arr + 5));

return 0;

// > gcc -O1 -g -o demo demo.c && ./demo

// arr[3] = 42

// *(arr + 3) = 42

// pointer of arr3 = 0x7ffd0753f1d0

// &arr[3] = 0x7ffd0753f1dc

// arr + 3 = 0x7ffd0753f1dc

// arr[5] = 99

// *(arr + 5) = 99

// pointer of arr5 = 0x7ffd0753f1d0

// &arr[5] = 0x7ffd0753f1e4

// arr + 5 = 0x7ffd0753f1e4

}

arr points to address 1000 (base address). arr + 3 points to address 1012 (base + 3 _sizeof(int)). _(arr + 3) retrieves the value at address 1012, which is 42. arr[3] does the same thing but with simpler syntax.

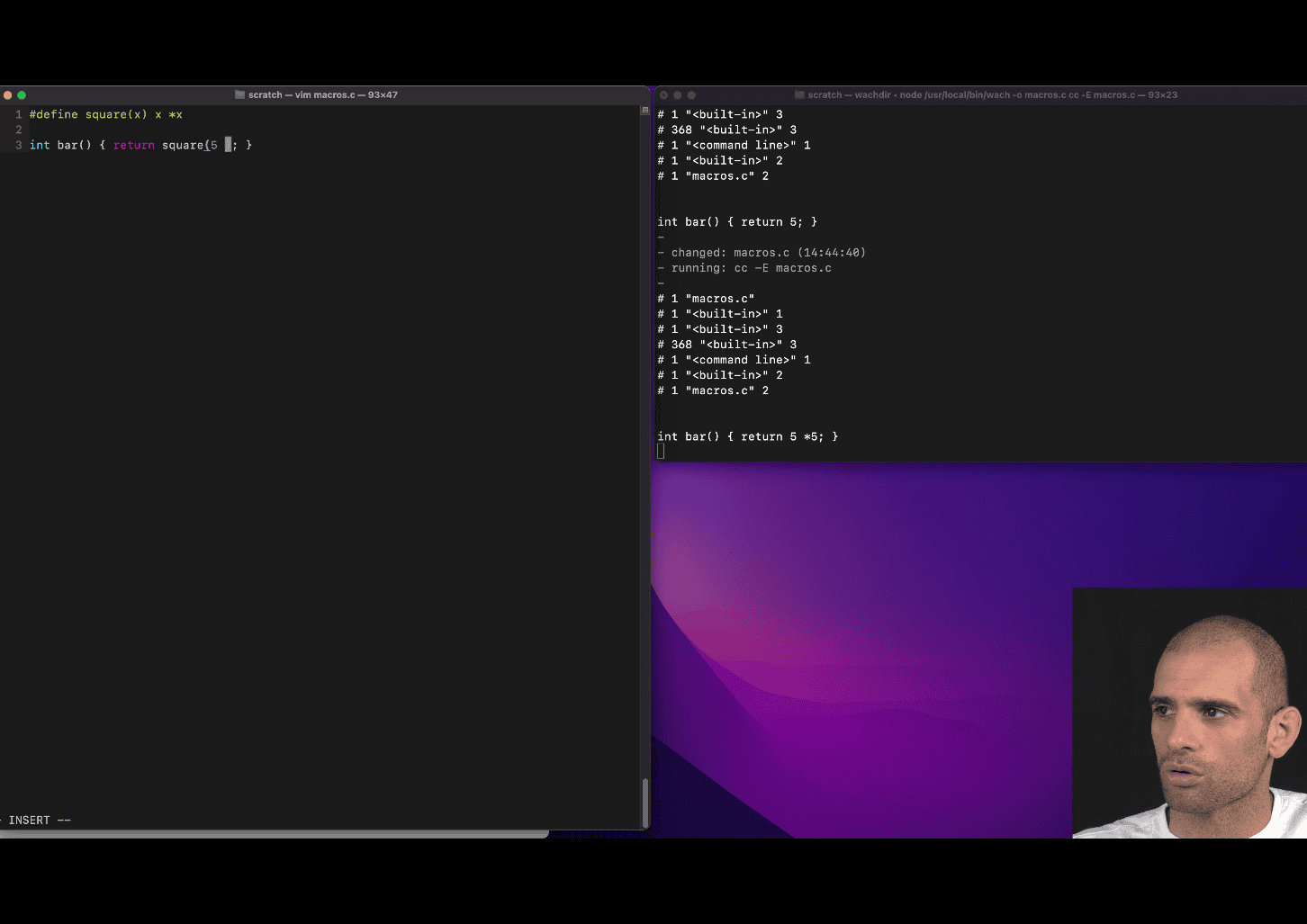

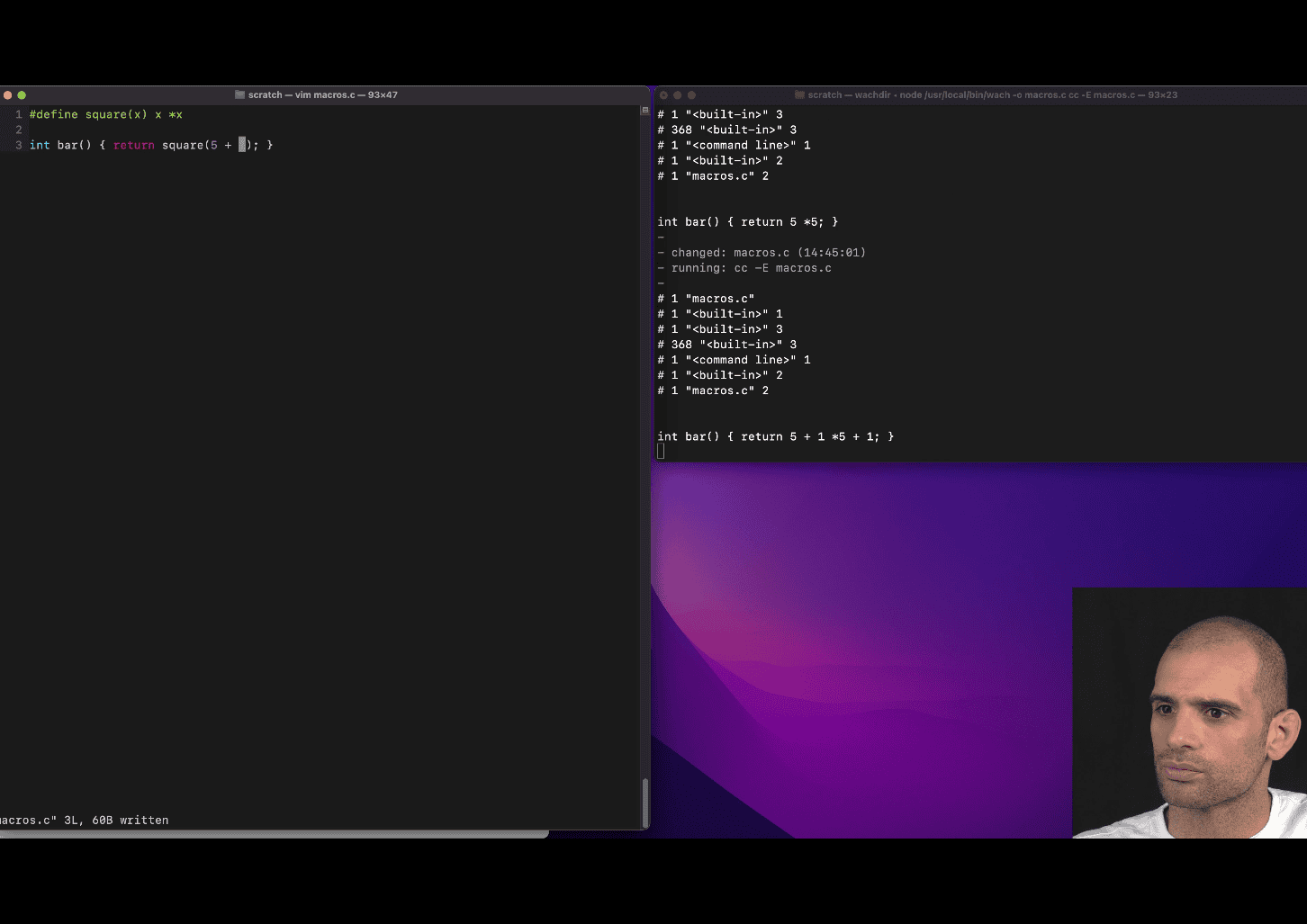

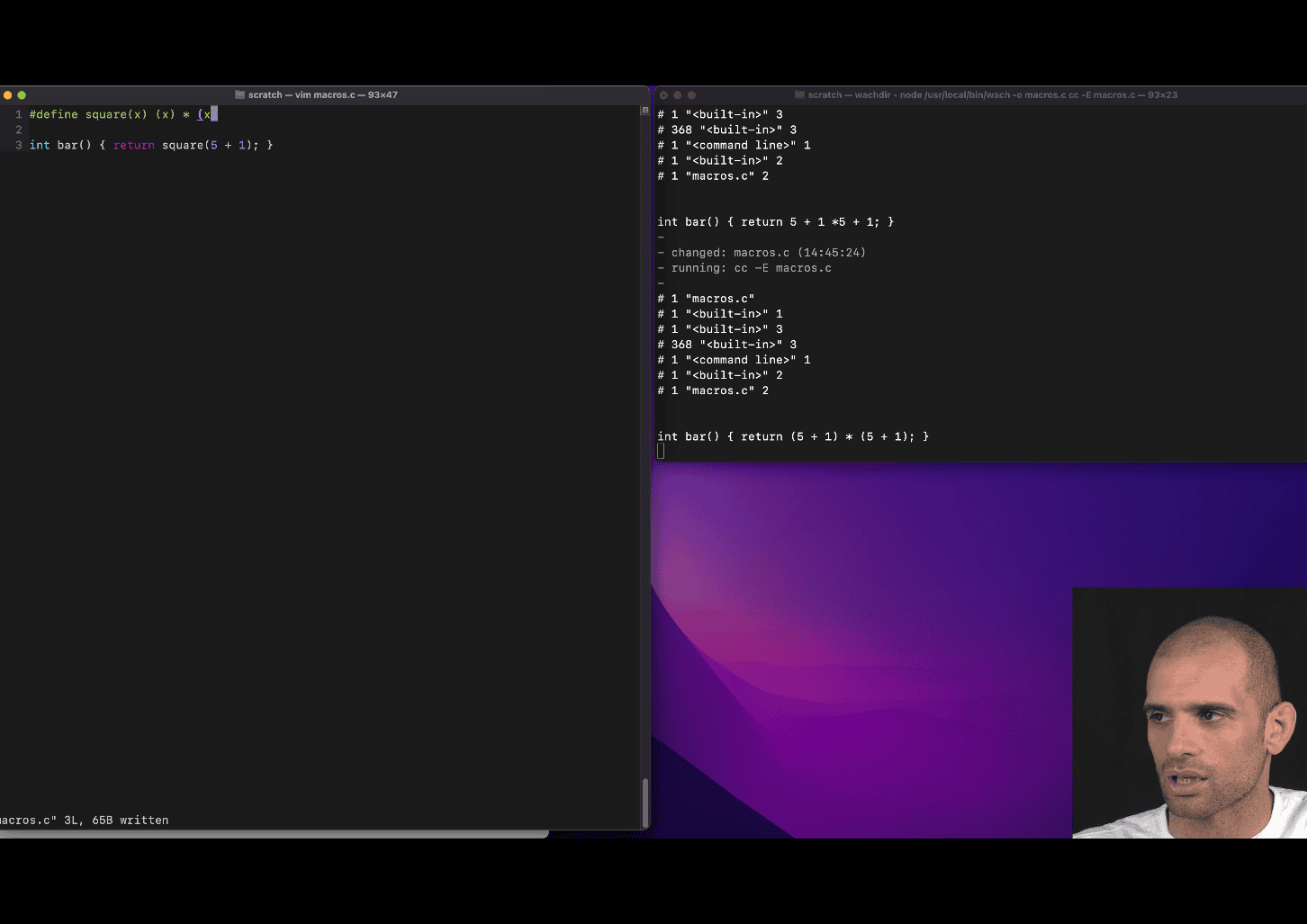

- The C pre-processor, macros and conditional inclusion

#define square(x) (x)*(x)

text replacement feature before compiler

include is also is part of this

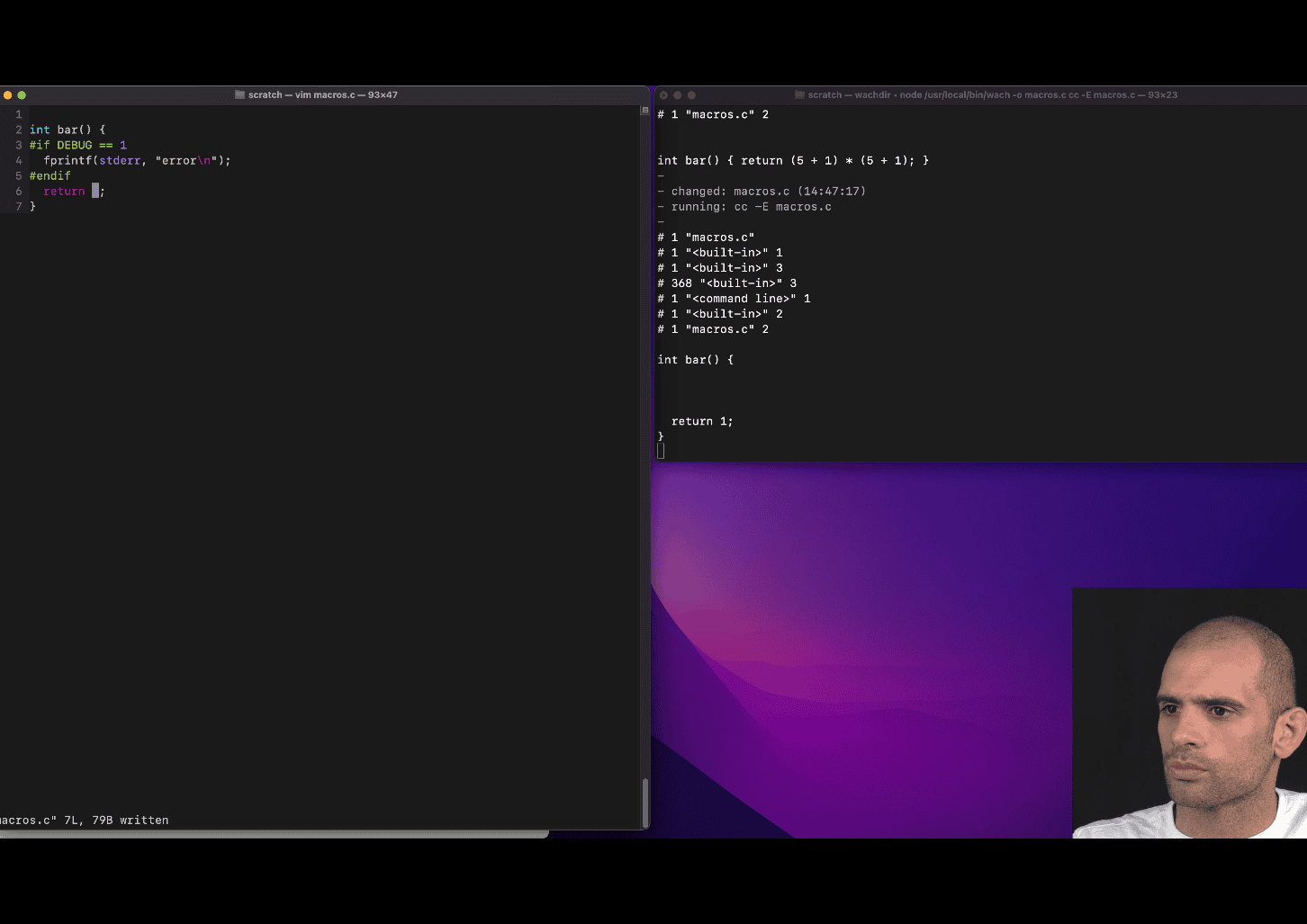

Your teacher is introducing you to conditional compilation in C using preprocessor directives like #if, #endif, and likely the concept of macros (e.g., DEBUG). The code snippet you provided has a few issues (e.g., syntax errors), but I’ll interpret it as a teaching example and explain the key concepts based on the corrected version:

int bar() {

#if DEBUG == 1

fprintf(stderr, "error\n");

#endif

return 1;

}Let’s break down what your teacher is trying to teach you.

1. Preprocessor Directives

The C preprocessor is a tool that processes your code before it is compiled. It handles directives starting with #, such as #if, #endif, #define, etc. In this example:

#if DEBUG == 1checks whether the macroDEBUGis defined and has the value1.#endifmarks the end of the conditional block.- The code inside the

#ifblock (i.e.,fprintf(stderr, "error\n");) is only included in the compiled program if the conditionDEBUG == 1is true.

2. Conditional Compilation

Conditional compilation allows you to include or exclude parts of your code based on certain conditions. This is useful for:

- Debugging: Including debug-specific code (like error messages) only when a debug mode is enabled.

- Portability: Including different code for different platforms or configurations.

- Feature toggling: Enabling or disabling features without changing the source code.

In this case:

- If

DEBUGis defined as1(e.g., via a#define DEBUG 1or a compiler flag like-DDEBUG=1), thefprintf(stderr, "error\n");line will be included in the compiled program, printing “error” to the standard error stream. - If

DEBUGis not defined or has a different value (e.g.,0), thefprintfline is excluded from the compiled program, as if it were never written.

3. The Role of the DEBUG Macro

The DEBUG macro is a common convention in C programming. It’s typically used to control whether debug-related code (like logging or error messages) is included. Your teacher is showing you how to:

- Use a macro to toggle debug output.

- Conditionally compile code based on whether debugging is enabled.

For example:

- During development, you might set

DEBUGto1to include diagnostic messages. - In production, you might set

DEBUGto0(or leave it undefined) to exclude these messages, making the program leaner and avoiding unnecessary output.

4. The fprintf(stderr, "error\n") Line

This line uses fprintf to print “error” to stderr (the standard error stream), which is typically used for error messages or diagnostics. The \n ensures a newline for clean output. This is a simple example of debug output that might help you diagnose issues during development.

5. Why This Matters

Your teacher is teaching you how to write flexible code that can behave differently depending on the build configuration. This is a powerful technique because:

- You can add debug code without worrying about it appearing in the final product.

- You can control program behavior (e.g., enabling/disabling features) using compiler flags or macro definitions.

- It introduces you to the preprocessor, which is a fundamental part of C programming.

6. Fixing the Code

The code you provided has a few issues:

- The

®character andtendifare likely typos. The correct directive is#endif. - The stray

3at the end is invalid and would cause a syntax error.

The corrected version (as shown above) is a minimal function that:

- Conditionally prints “error” to

stderrifDEBUGis1. - Always returns

1.

7. How DEBUG Is Set

The DEBUG macro can be defined in several ways:

- In the code: Using

#define DEBUG 1before the#ifdirective. - Via the compiler: Passing a flag like

-DDEBUG=1when compiling (e.g.,gcc -DDEBUG=1 program.c). - In a build system: Tools like

makeor CMake can set macros based on build configurations.

For example, if you compile with DEBUG set to 1, the compiled program includes the fprintf call. If you compile without DEBUG or with DEBUG set to 0, the fprintf is omitted.

8. Example Compilation Scenarios

Assume the corrected code:

#include <stdio.h>

#define DEBUG 1

int bar() {

#if DEBUG == 1

fprintf(stderr, "error\n");

#endif

return 1;

}

int main() {

bar();

return 0;

}- With

DEBUG == 1: Running the program prints “error” tostderrand returns1frombar(). - With

DEBUG == 0(change#define DEBUG 0): Thefprintfline is excluded, so nothing is printed, butbar()still returns1.

If you compile without defining DEBUG (e.g., remove the #define), the #if DEBUG == 1 condition is false (since DEBUG is undefined and treated as 0 in preprocessor arithmetic), so the fprintf is excluded.

9. Broader Lesson

Your teacher is likely building on this to teach you:

- Modular code: Use preprocessor directives to make code adaptable to different scenarios.

- Debugging techniques: Conditionally include diagnostic output to troubleshoot issues.

- Preprocessor mechanics: Understand how the preprocessor manipulates code before compilation.

- Real-world practices: Conditional compilation is widely used in professional C projects (e.g., in libraries, operating systems, or embedded systems).

10. Practice to Reinforce

To deepen your understanding:

- Try compiling the code with and without

DEBUGdefined (e.g., using-DDEBUG=1or-DDEBUG=0withgcc). - Modify the

#ifcondition to check other values (e.g.,#if DEBUG == 2) and observe the behavior. - Add more debug output (e.g., print a variable’s value) inside the

#ifblock. - Experiment with other preprocessor directives like

#ifdef DEBUG(checks ifDEBUGis defined, regardless of its value) or#elseto handle alternative cases.

11. Connection to Pointers (from Your Previous Question)

If this lesson follows your previous question about pointers (arr[3] vs. *(arr + 3)), your teacher might be systematically introducing you to core C concepts:

- Pointers: How memory is accessed and manipulated.

- Preprocessor: How code is conditionally included before compilation.

- These are foundational for writing efficient, flexible, and debuggable C programs.

If you have more questions about this code, the preprocessor, or how it ties into pointers, let me know!

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# hex_diff.py – compute the difference between two hex values (provided as strings)

# usage: python hex_diff.py "0x7ffd0753f1d0" "0x7ffd0753f1dc"

import sys

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print("usage: python hex_diff.py <hex1> <hex2>")

sys.exit(1)

try:

hex1 = int(sys.argv[1], 16)

hex2 = int(sys.argv[2], 16)

diff = abs(hex2 - hex1)

print("Difference (decimal):", diff)

print("Difference (hex):", hex(diff))

except ValueError as e:

print("Error: invalid hex value –", e)

easy way to diff the hex vaule

#include <stdio.h>

/* Define a debug flag. Set to 0 to disable debug output. */

#define DEBUG 1

/* A debug macro that prints a message (using do-while(0) for safety). */

#define DEBUG_PRINT(msg) \

do { \

if (DEBUG) \

fprintf(stderr, "DEBUG: %s\n", (msg)); \

} while (0)

/* A utility macro to compute the minimum of two values. */

#define MIN(a, b) ((a) < (b) ? (a) : (b))

/* Define a platform flag (e.g., PLATFORM_WINDOWS) for conditional compilation.

*/

#define PLATFORM_WINDOWS 1

#define PLATFORM_LINUX 0

/* Conditional compilation block: define CLEAR_SCREEN based on the platform. */

#if PLATFORM_WINDOWS

#define CLEAR_SCREEN "cls"

#elif PLATFORM_LINUX

#define CLEAR_SCREEN "clear"

#else

#define CLEAR_SCREEN ""

#endif

int main() {

/* Demonstrate debug macro. */

DEBUG_PRINT("Starting program.");

/* Demonstrate utility macro MIN. */

int a = 5, b = 3;

printf("MIN(%d, %d) = %d\n", a, b, MIN(a, b));

/* Demonstrate conditional compilation (e.g., clearing the screen). */

printf("Clearing screen (using CLEAR_SCREEN macro)...\n");

/* Uncomment the next line to actually clear the screen (requires stdlib.h).

*/

/* system(CLEAR_SCREEN); */

DEBUG_PRINT("Program finished.");

return 0;

}

#define DEBUG_PRINT(msg) \

do { \

if (DEBUG) \

fprintf(stderr, "DEBUG: %s\n", (msg)); \

} while (0)

this make the debug fuction happen, debug 1 → enable it , 0 disable

- convince

- A brief overview of structs in C

group all kind of variable

object without method

struct will ofter use the concept of pointer

when you use struct inside fucnction like arg , or return large struct will be copy on stack and it will take time and space

#include <stdio.h>

struct user {

int age;

short postcode;

char *name; // char pointer , struct will user struct int 8 byte pointer field

};

int main() {

struct user u = {25, 10000, "Bob"};

struct user u2 = {17, 20000, "Alice"};

struct user u3 = {17, 20000, "Peter"};

struct user *p = &u3;

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u.name, u.age);

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u2.name, u2.age);

// printf("%s is %d years old\n", p.name); -> this won't work

printf("%s is %d years old\n", (*p).name, (*p).age);

printf("%s is %d years old\n", p->name, p->age);

printf("ok\n");

}

generally, struct is gonna be lay out continuely without space in the order you specific , one thing is about alignment

#include <stdio.h>

struct user {

int age; // 4 bytes

short postcode; // 2bytes

char *name; // char pointer , struct will user struct int 8 byte pointer field

};

int main() {

struct user u = {25, 10000, "Bob"};

struct user u2 = {17, 20000, "Alice"};

struct user u3 = {17, 20000, "Peter"};

struct user *p = &u3;

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u.name, u.age);

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u2.name, u2.age);

// printf("%s is %d years old\n", p.name); -> this won't work

printf("%s is %d years old\n", (*p).name, (*p).age);

printf("%s is %d years old\n", p->name, p->age);

printf("ok\n");

printf(" this is the address of %p %p %p %p\n ", &u, &(u.age), &(u.postcode),

&(u.name));

}

// Bob is 25 years old

// Alice is 17 years old

// Peter is 17 years old

// Peter is 17 years old

// ok

// this is the address of 0x7ffdb4a3d1b0 0x7ffdb4a3d1b0 0x7ffdb4a3d1b4

// 0x7ffdb4a3d1b8

// %

struct user users[2] = {{1, 10000, "foo"}, {2, 10001, "bar"}};

printf("%s is %d years old\n", users[1].name, users[1].age);

c is need to be able to these kind of array in a constant time muiltiple dimensional arrays in c

struct is always in a certain size

printf("One struct is %lu bytes\n", sizeof(struct user));

printf("users array is at %p, \"%s\" is located at %p\n", users,

users[1].name, &users[1].name);

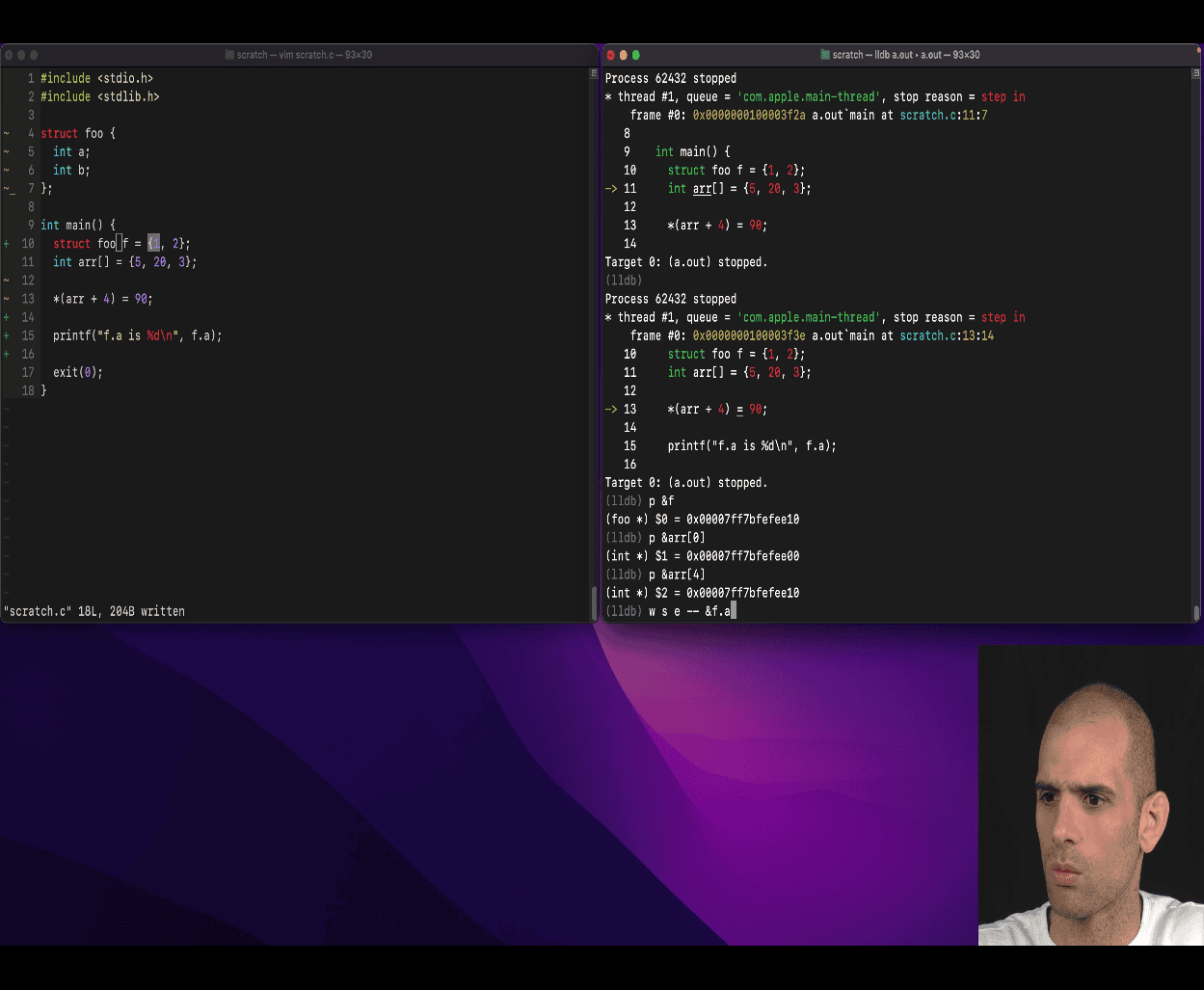

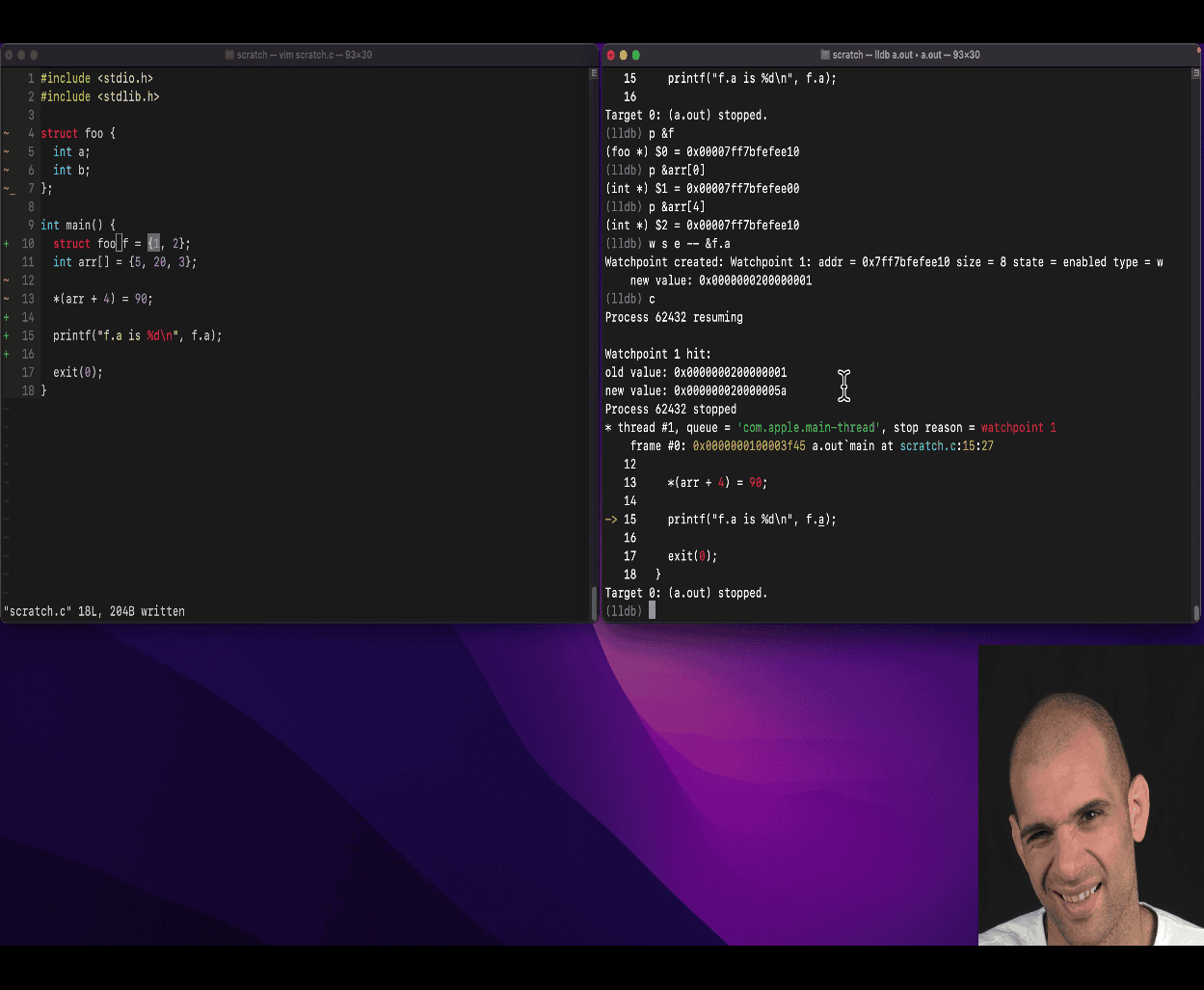

explain how to count 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 to 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8

users array is at 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0, “bar” is located at 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8

Your teacher is introducing you to structs in C, a fundamental concept for grouping related data, and tying it to other key ideas like pointers, memory layout, arrays, and memory alignment. The code snippets and notes you provided illustrate how structs work, their memory organization, and practical considerations like accessing fields or managing large structs. Below, I’ll explain the concept of structs based on your teacher’s examples, address the memory address calculation (e.g., from 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 to 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8), and clarify the key lessons your teacher is emphasizing. I’ll keep it concise, practical, and focused on your current learning level, building on your prior questions about pointers and macros.

1. Overview of Structs in C

A struct (short for structure) in C is a user-defined data type that groups variables of different types into a single unit. Think of it as an “object without methods” (as your teacher noted), where you bundle related data together.

Key Characteristics

-

Grouping Variables: A struct combines different types (e.g.,

int,short,char*) into one cohesive type.struct user { int age; // 4 bytes short postcode; // 2 bytes char *name; // 8 bytes (pointer on 64-bit systems) }; -

Contiguous Memory Layout: Struct fields are laid out in memory sequentially in the order declared, though alignment (padding) may add extra bytes for efficiency.

-

Fixed Size: Each struct instance has a predictable size, determined by its fields and alignment (e.g.,

sizeof(struct user)). -

No Methods: Unlike objects in languages like C++ or Java, C structs only hold data, not functions.

-

Pointers and Structs: Structs are often used with pointers for efficiency, especially when passing to functions or returning from them, to avoid copying large data.

Why Structs Are Useful

- Organize related data (e.g., a

userwithage,postcode, andname). - Enable arrays of structs for constant-time access (like

users[1]). - Support complex data structures (e.g., linked lists, trees) when combined with pointers.

2. Key Concepts Your Teacher Is Teaching

Your teacher’s code and notes emphasize several critical aspects of structs, which I’ll explain using the provided examples.

a) Creating and Accessing Structs

You can create struct instances and access their fields using the dot (.) operator:

struct user u = {25, 10000, "Bob"};

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u.name, u.age); // Bob is 25 years old- Initialization:

uis initialized with values forage,postcode, andnamein the order declared. - Dot Operator (

.): Access fields directly (e.g.,u.name).

b) Structs and Pointers

Structs are often used with pointers to avoid copying large data. You access fields through a pointer using:

- Dereference (

*):(*p).namedereferences the pointerpand accesses thenamefield. - Arrow Operator (

->):p->nameis a shorthand for(*p).name.

struct user u3 = {17, 20000, "Peter"};

struct user *p = &u3;

printf("%s is %d years old\n", (*p).name, (*p).age); // Peter is 17 years old

printf("%s is %d years old\n", p->name, p->age); // Peter is 17 years old- Why

p.nameFails:pis a pointer, not a struct, sop.nameis invalid. You must dereference ((*p).name) or use->(p->name). - Lesson: Pointers are common with structs for efficiency and flexibility, especially in functions or dynamic memory allocation.

c) Memory Layout and Alignment

Struct fields are laid out contiguously in memory, but alignment may add padding to ensure fields align with memory boundaries (e.g., 4-byte or 8-byte boundaries for performance).

struct user {

int age; // 4 bytes

short postcode; // 2 bytes + 2 bytes padding (to align next field)

char *name; // 8 bytes

};-

Size Calculation:

int age: 4 bytes.short postcode: 2 bytes, but compilers often add 2 bytes of padding to align the next field (name) on an 8-byte boundary (common on 64-bit systems).char *name: 8 bytes (pointer size on 64-bit systems).- Total:

4 + 2 + 2 + 8 = 16 bytes(confirmed withsizeof(struct user)).

-

Example Output:

printf("One struct is %lu bytes\n", sizeof(struct user)); // One struct is 16 bytes -

Memory Addresses:

printf("this is the address of %p %p %p %p\n", &u, &(u.age), &(u.postcode), &(u.name)); // Output: 0x7ffdb4a3d1b0 0x7ffdb4a3d1b0 0x7ffdb4a3d1b4 0x7ffdb4a3d1b8&uand&(u.age)are the same (base address of the struct).&(u.postcode)is at0x7ffdb4a3d1b4(base + 4 bytes).&(u.name)is at0x7ffdb4a3d1b8(base + 4 + 2 + 2 = 8 bytes).

-

Lesson: Structs are laid out sequentially, but padding ensures alignment, affecting the total size and field offsets.

d) Arrays of Structs

Structs can be stored in arrays, allowing constant-time access with indexing:

struct user users[2] = {{1, 10000, "foo"}, {2, 10001, "bar"}};

printf("%s is %d years old\n", users[1].name, users[1].age); // bar is 2 years old- Memory Layout:

users[0]starts at the array’s base address (e.g.,0x7ffe6b1f9ea0).users[1]is atbase + sizeof(struct user)(e.g.,0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 + 16 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb0).

- Constant-Time Access:

users[i]computes the address asbase + i * sizeof(struct user), enabling fast access. - Lesson: Arrays of structs are efficient for managing collections of structured data.

e) Passing Structs to Functions

Your teacher noted that passing large structs to functions or returning them copies the entire struct onto the stack, which is slow and memory-intensive:

void print_user(struct user u) {

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u.name, u.age);

}- Problem:

uis copied (16 bytes forstruct user), which is inefficient for large structs. - Solution: Pass a pointer instead:

void print_user(struct user *u) {

printf("%s is %d years old\n", u->name, u->age);

}- Why: Only the pointer (8 bytes) is copied, and

->accesses fields efficiently. - Lesson: Use pointers to structs in functions to save time and space.

3. Memory Address Calculation: 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 to 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8

Your teacher’s example shows:

users array is at 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0, "bar" is located at 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8

x python hex_diff.py “0x7ffe6b1f9ea0” “0x7ffe6b1f9eb8” Difference (decimal): 24 Difference (hex): 0x18

This refers to the address of the users array and the address of users[1].name (the name field of users[1]). Let’s calculate the difference and explain why it’s 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8.

Step-by-Step Calculation

-

Array Base Address:

usersis at0x7ffe6b1f9ea0.users[0]starts at0x7ffe6b1f9ea0.users[1]starts at0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 + sizeof(struct user) = 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 + 16 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb0.

-

Struct Layout:

- Inside

users[1]:age: 4 bytes (offset 0:0x7ffe6b1f9eb0).postcode: 2 bytes + 2 bytes padding (offset 4:0x7ffe6b1f9eb4).name: 8 bytes (offset 8:0x7ffe6b1f9eb8).

&users[1].nameis atusers[1] base + 8 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb0 + 8 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8.

- Inside

-

Hex Arithmetic:

0x7ffe6b1f9ea0(array base).- Add

16(0x10 in hex) forusers[1]:0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 + 0x10 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb0. - Add

8(offset ofname):0x7ffe6b1f9eb0 + 0x8 = 0x7ffe6b1f9eb8. - Result:

0x7ffe6b1f9eb8, matching&users[1].name.

-

Why This Matters:

- The difference (

0x7ffe6b1f9eb8 - 0x7ffe6b1f9ea0 = 0x18or 24 bytes) shows:- 16 bytes for

users[0](entirestruct user). - 8 bytes to reach the

namefield inusers[1].

- 16 bytes for

- This demonstrates how structs and arrays are laid out in memory, with predictable offsets.

- The difference (

Lesson

- Struct fields have fixed offsets, determined by their order and alignment.

- Arrays of structs are contiguous, with each element offset by

sizeof(struct). - Pointer arithmetic (e.g.,

users + 1) computes addresses based onsizeof(struct user).

4. Broader Lessons from Your Teacher

Your teacher is building a foundation for understanding how C manages data and memory:

- Structs as Data Containers: Group related data for clarity and organization.

- Memory Layout: Structs are contiguous, but alignment adds padding, affecting size and field offsets.

- Pointers and Efficiency: Use pointers to structs for functions, dynamic allocation, or large data to avoid copying.

- Arrays and Constant-Time Access: Struct arrays enable fast, indexed access, critical for data structures.

- Practical Considerations: Understand memory addresses and sizes (

sizeof) for debugging and optimization.

Connection to Previous Questions

-

Pointers: Your earlier question about

arr[3]vs.*(arr + 3)ties to structs. Struct arrays (users[i]) use similar pointer arithmetic, and->is a pointer-based access method. -

Macros: You could use macros to simplify struct operations, e.g.:

#define PRINT_USER(u) printf("%s is %d years old\n", (u)->name, (u)->age)This works for both

PRINT_USER(&u)andPRINT_USER(p).

5. Practice to Reinforce

To solidify these concepts:

-

Size and Alignment: Use

sizeofto check the size of different structs. Reorder fields (e.g.,char*,int,short) and observe padding changes. -

Pointer Access: Write a function that takes a

struct user*and prints its fields using->. -

Array Iteration: Loop over a

struct userarray and print all users.for (int i = 0; i < 2; i++) { printf("%s\n", users[i].name); } -

Address Arithmetic: Print addresses of all fields in

users[0]andusers[1]to confirm offsets. -

Dynamic Allocation: Create a

struct userdynamically withmallocand access it via a pointer.

6. Key Takeaways

- Structs group variables into a single type, laid out contiguously with possible padding for alignment.

- Pointers are essential for efficient struct handling (e.g.,

->, passing to functions). - Arrays of structs enable fast access and are stored contiguously.

- Memory Layout: Understand

sizeof, field offsets, and alignment for debugging and optimization. - Practical Use: Structs are the backbone of complex data structures and real-world C programs.

If you want more examples, clarification on alignment, or help with a specific struct-related task (e.g., multi-dimensional arrays, dynamic allocation), let me know!

#include <stdio.h>

// Define a simple struct to represent a student

struct student {

int id; // 4 bytes

short grade; // 2 bytes + 2 bytes padding

char *name; // 8 bytes on 64-bit systems

}; // Total: 16 bytes

int main() {

// Create an array of 2 students

struct student students[2] = {{1001, 85, "Alice"}, {1002, 92, "Bob"}};

// Print the size of the struct and array

printf("Size of struct student: %lu bytes\n", sizeof(struct student));

printf("Size of students array: %lu bytes\n", sizeof(students));

// Print base address of array and first student

printf("\nArray base address: %p\n", (void *)students);

printf("First student address: %p\n", (void *)&students[0]);

// Access using array notation

printf("\nUsing array notation:\n");

printf("Student 1: %s (ID: %d, Grade: %d)\n", students[0].name,

students[0].id, students[0].grade);

// Access using pointer notation

struct student *ptr = &students[1];

printf("\nUsing pointer notation:\n");

printf("Student 2: %s (ID: %d, Grade: %d)\n", ptr->name, ptr->id, ptr->grade);

// Show field addresses for first student

printf("\nField addresses for first student:\n");

printf("id field: %p\n", (void *)&students[0].id);

printf("grade field: %p\n", (void *)&students[0].grade);

printf("name field: %p\n", (void *)&students[0].name);

return 0;

}

// Size of struct student: 16 bytes

// Size of students array: 32 bytes

//

// Array base address: 0x7ffc5859c1d0

// First student address: 0x7ffc5859c1d0

//

// Using array notation:

// Student 1: Alice (ID: 1001, Grade: 85)

//

// Using pointer notation:

// Student 2: Bob (ID: 1002, Grade: 92)

//

// Field addresses for first student:

// id field: 0x7ffc5859c1d0

// grade field: 0x7ffc5859c1d4- think before putting struct in functino , depends on situation

- The generic pointer (void *) in C (16:21)

To address your question, let’s assume that the context is translating the Python

To address your question, let’s assume that the context is translating the Python Box class scenario into C, where b2 is an object (or struct) similar to the Python example, and we are dealing with pointers and type casting. In C, b2.value would likely be a pointer or a field in a struct, and you’re asking about the expressions *(int*)b2.value and (int*)b2.value. Let’s break this down clearly.

Context Setup

Assume we have a C struct analogous to the Python Box class:

typedef struct Box {

char* name; // String for the name

void* value; // Generic pointer for the value (to mimic Python's flexibility)

} Box;Suppose:

bis aBoxstruct withname = "foo"andvaluepointing to an integer (e.g.,3).b2is aBoxstruct withname = "bar"andvaluepointing tob(i.e.,b2.valueholds the address of theBoxstructb).

Example initialization:

Box b = {"foo", malloc(sizeof(int))}; // Allocate memory for an int

*(int*)b.value = 3; // Store 3 in the allocated memory

Box b2 = {"bar", &b}; // b2.value points to bNow, let’s evaluate the expressions *(int*)b2.value and (int*)b2.value.

1. (int*)b2.value

- What it does: This is a type cast of

b2.valueto a pointer to an integer (int*). - Explanation:

b2.valueis avoid*(in our struct definition), which holds the address of theBoxstructb.- Casting it to

int*with(int*)b2.valuetells the compiler to treat the address stored inb2.valueas if it points to an integer. - The result is an

int*(a pointer to an integer), but it does not dereference the pointer—it simply reinterprets the address.

- Value: The address of

b(i.e.,&b), but now typed asint*instead ofvoid*. - Correctness: This cast is generally unsafe because

b2.valuepoints to aBoxstruct, not an integer. Treating the starting address of aBoxstruct as anint*could lead to undefined behavior if you try to use it, as the memory layout of aBoxstruct (starting with achar*forname) is not the same as anint.

2. *(int*)b2.value

- What it does: This expression first casts

b2.valueto anint*(as above) and then dereferences the resulting pointer to access the integer value at that address. - Explanation:

- As with

(int*)b2.value,(int*)b2.valuecastsb2.value(which is&b) to anint*. - The

*operator then tries to dereference thisint*to retrieve the integer value at the address&b. - Since

&bis the address of aBoxstruct, dereferencing it as anintassumes the firstsizeof(int)bytes of theBoxstruct represent an integer, which is incorrect and leads to undefined behavior.

- As with

- Value: The result is undefined because the memory at

&bcontains aBoxstruct (starting with achar*forname), not an integer. The program might crash, return garbage data, or behave unpredictably. - Correctness: This operation is invalid in this context because

b2.valuepoints to aBoxstruct, not an integer.

Key Difference

-

(int*)b2.value:- Returns a pointer (

int*) by castingb2.valueto anint*. - It does not access the memory at that address; it only changes the type of the pointer.

- Result: The address

&b, typed asint*. - Use case: You might use this if you need to pass the address to a function expecting an

int*, but in this case, the cast is unsafe unlessb2.valueactually points to an integer.

- Returns a pointer (

-

*(int*)b2.value:- Dereferences the casted pointer to access the value at the address.

- Attempts to interpret the memory at

&bas an integer, which is invalid in this context and causes undefined behavior. - Result: Undefined (likely garbage or a crash).

- Use case: This would only be valid if

b2.valuepointed to an actual integer, which it does not in this scenario.

Why This Happens

In the Python example, b2.value is the Box object b, and b2.value.name accesses b’s name field ("foo"). In C, b2.value is a pointer to the Box struct b. If you want to access b’s name field in C, you would use:

((Box*)b2.value)->nameThis casts b2.value to a Box* (since it points to a Box struct) and accesses the name field, which would return "foo".

However, both (int*)b2.value and *(int*)b2.value are incorrect in this context because they assume b2.value points to an integer, when it actually points to a Box struct.

Correct Approach

If you intended to access the integer value stored in b.value (i.e., 3), you would need to:

- Cast

b2.valueto aBox*to access theBoxstructb. - Then access

b.valueand cast that to anint*to get the integer.

For example:

*(int*)((Box*)b2.value)->valueb2.valueis&b(avoid*pointing to aBox).(Box*)b2.valuecasts it to aBox*.((Box*)b2.value)->valueaccessesb.value, which is avoid*pointing to an integer.(int*)((Box*)b2.value)->valuecastsb.valueto anint*.*(int*)((Box*)b2.value)->valuedereferences to get the integer3.

Summary

(int*)b2.value: Castsb2.valueto anint*, giving a pointer to&btyped asint*. Unsafe in this context.*(int*)b2.value: Dereferences the casted pointer, attempting to read an integer from&b, which causes undefined behavior.- To access

b’sname("foo") in C, use((Box*)b2.value)->name. - To access

b’svalue(3), use*(int*)((Box*)b2.value)->value.