csprimer-algorithms

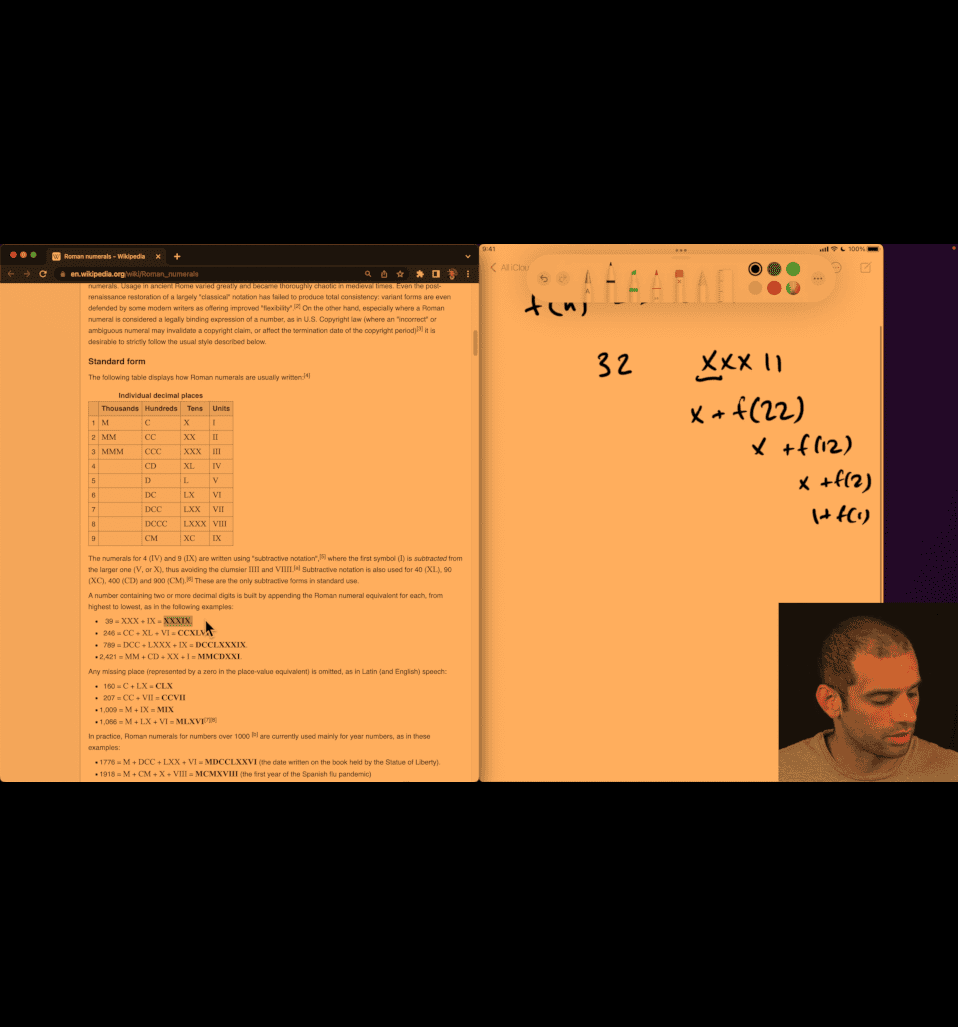

002 Convert to Roman

- understand the problem

- start from smaller problem

- found pattern, solve by recursions or loop etc

- create your own test, think line by line?

plan:

recursively → substract the larger problem → smaller

scratch and keep planing:

def f(n):

for d,r:

if d<=n:

return r+f(n-d)

return ""

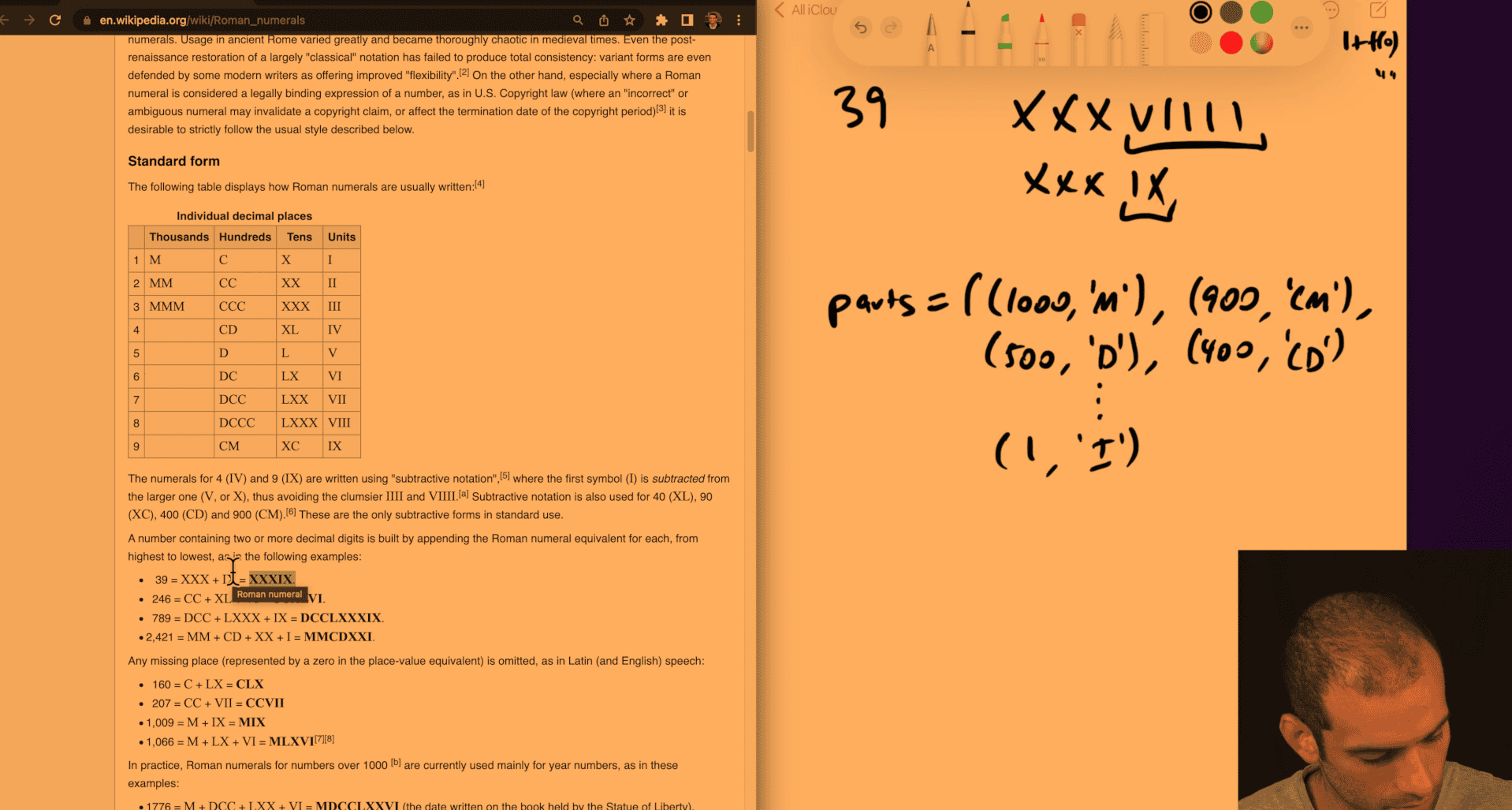

parts = [

(1000, "M"),

(900, "CM"),

(500, "D"),

(400, "CD"),

(100, "C"),

(90, "XC"),

(50, "L"),

(40, "XL"),

(10, "X"),

(9, "IX"),

(5, "V"),

(4, "IV"),

(1, "I"),

]

def f(n):

if n <= 0:

return ""

for d, r in parts:

if d <= n:

return r + f(n - d)

return ""

if __name__ == "__main__":

cases = ((39, "XXXIX"), (2421, "MMCDXXI"), (1066, "MLXVI"))

for n, x in cases:

assert f(n) == x

print("ok")more overkill feature:

binary search bisect

from bisect import bisect_right

values = [1, 4, 5, 9, 10, 40, 50, 90, 100, 400, 500, 900, 1000]

symbols = ["I", "IV", "V", "IX", "X", "XL", "L", "XC", "C", "CD", "D", "CM", "M"]

def f(n):

r = ""

while n > 0:

i = bisect_right(values, n) - 1 # largest value <= n

r += symbols[i]

n -= values[i]

return r

003 Correct binary search.mp4

from typing import List, Optional

def binsearch(nums: List[int], target: int) -> Optional[int]:

lo = 0

hi = len(nums) - 1

# Invariant: if target is in nums, then it is within indices [lo, hi]

while lo <= hi:

mid = lo + (hi - lo) // 2 # avoids overflow and biases toward lower mid

value = nums[mid]

if value == target:

return mid

if value < target:

lo = mid + 1 # target, if present, is in [mid+1, hi]

else:

hi = mid - 1 # target, if present, is in [lo, mid-1]

return None

#if name=main:

a = [-5, -2, 0]

b = [0, 2, 3, 4, 9]

cases = [

(a, -5, 0),

(a, -2, 1),

(a, 0, 2),

(a, 2, None),

(a, -3, None),

(b, 0, 0),

(b, 3, 2),

(b, 4, 3),

(b, 2, 1),

(b, 9, 4),

]

for nums, n, exp in cases:

assert binsearch(nums, n) == exp, (nums, n, exp, binsearch(nums, n))

print('ok')

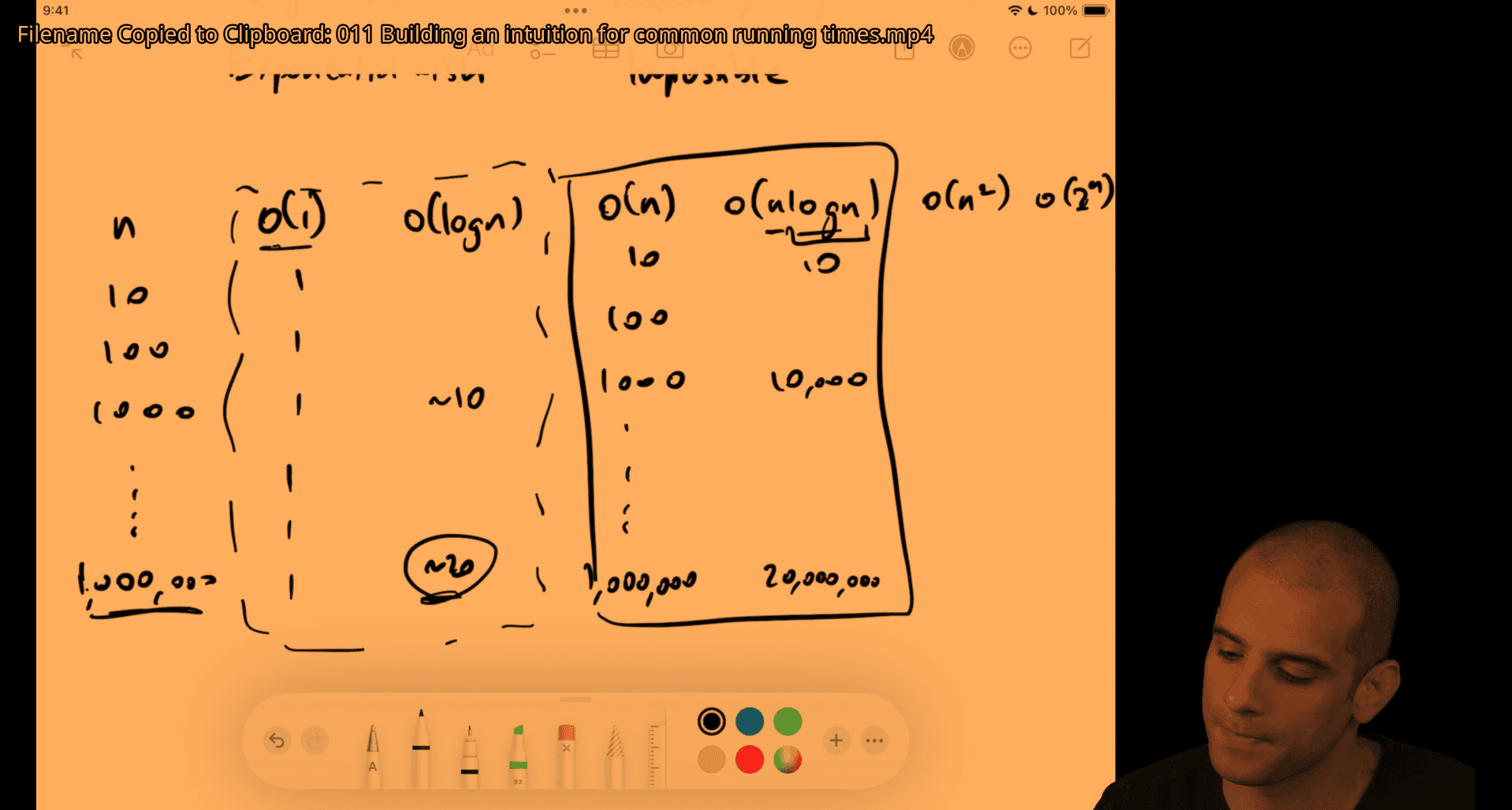

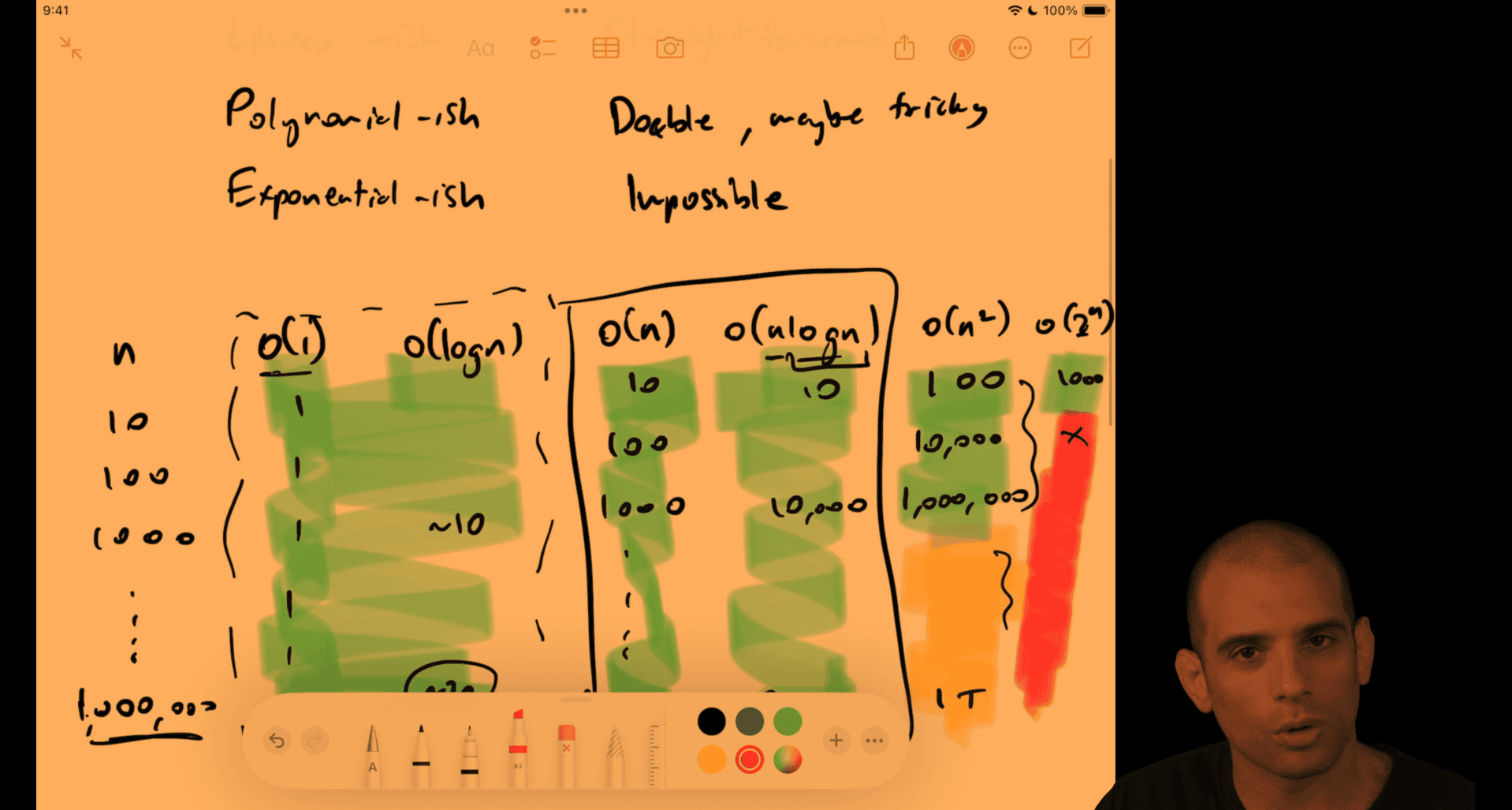

010 The enormous difference between polynomial and exponential.mp4

O(n^2) vs O(2^n)

011 Building an intuition for common running times.mp4

- o(n^2) is ok if n ⇐1000 but not for o(2^n)

006 Finding duplicates

Asymptotic Analysis and Finding Duplicates

Introduction: Asymptotic Analysis as a Tool

The Love-Hate Relationship

- Many engineers have mixed feelings about Big O notation

- Common issues: under-using and over-using it

- It’s one tool in your toolkit, not the only thing

What Asymptotic Analysis Does

Theoretical perspective:

- Allows speaking about trade-offs between approaches

- Agnostic of the specific system running the code

- Enables algorithms from the 1950s to remain relevant today

- Part of a multi-decade (approaching multi-century) conversation about algorithms

Practical reality:

- You cannot be agnostic of your actual system

- Real systems matter: machine, language, data characteristics, RAM constraints

- Some of the most important decisions depend on context

The balance:

- Theory helps us speak generally and universally

- Practice requires considering the actual system

- Both perspectives are necessary

The Problem: Finding Duplicates

Task: Write a function hasDuplicate(array) that returns true if there are duplicate integers in an array, false otherwise.

Three different engineers propose three different approaches.

Solution 1: Nested Loops (Compare Everything)

Approach

- For each element in the array, compare it to every other element

- Can optimize by using symmetry (comparing A to B but not B to A)

Complexity Analysis

Time: O(n²)

- Work grows as the area of a square (n × n)

- Even with symmetry optimization (comparing only half), it’s still fundamentally n²

- Constant factors (like 1/2) don’t change the complexity class

Space: O(1)

- No extra data structures needed

Growth Example

- Going from 10 to 20 elements: 100 → 400 comparisons

- Going from 10 to 100 elements: 100 → 10,000 comparisons

- Substantial growth as n increases

When to Use

- Simple and straightforward

- Good for small, bounded n

- Easy to understand and maintain

- Not ideal for large databases or unbounded growth

Solution 2: Sort Then Check Adjacent Pairs

Approach

- Sort the array (non-destructive or sort a copy)

- Iterate through checking adjacent pairs

- If any adjacent pair is equal, there’s a duplicate

Complexity Analysis

Time: O(n log n)

- Sorting: O(n log n) - this is “astonishing” because most intuitive sorts are O(n²)

- Iteration: O(n)

- Combined: O(n log n) (the n log n term dominates)

Space: O(n) or O(1)

- O(n) if you need to create a copy (non-destructive)

- O(1) if you can sort in-place

Understanding n log n

Key insight: n log n is much closer to linear than to n²

Concrete examples:

- log₂(1024) = 10 (since 2¹⁰ = 1024)

- log₂(1 billion) ≈ 30 (since 2³⁰ ≈ 1 billion)

- The logarithm grows very slowly compared to n

Comparison:

- For 10,000 elements: iteration takes 10,000 units of work

- n log n is substantially better than n² for large n

When to Use

- Better than O(n²) for large n

- May require extra space if sorting in-place isn’t possible

- More complex than nested loops

Solution 3: Hash Map/Set (Single Pass)

Approach

- Iterate through array once

- For each element, check if it’s already in a hash map/set

- If yes → duplicate found

- If no → add it to the hash map/set

Complexity Analysis

Time: O(n)

- Single pass through array: O(n)

- Hash map operations (insert, lookup): O(1) average case

- Combined: O(n)

Space: O(n)

- Must store all elements in the hash map

- Space grows proportionally with input size

Comparison to Solution 2

Theoretically: O(n) is better than O(n log n)

- There exists some n where Solution 3 is definitely faster

Practically:

- Requires O(n) space (Solution 2 might use O(1) if in-place)

- May not be feasible if RAM is constrained

- More complex than Solution 1

When to Use

- Best theoretical time complexity

- Requires extra space

- Consider: Do we have enough RAM? Is n large enough that the difference matters?

Key Insights About Asymptotic Analysis

What It Discards

-

Constant factors

- O(n²) vs O(½n²) are the same complexity class

- The 1/2 optimization doesn’t change the analysis

-

Non-dominant terms

- O(n log n + n) = O(n log n)

- The +n term is dominated by n log n

-

Exact counts

- Focus is on pattern of growth, not precise numbers

Complexity Classes That Matter

In practice, only a handful of complexity classes make a meaningful difference:

- Constant: O(1)

- Linear: O(n)

- Logarithmic: O(log n)

- Linearithmic: O(n log n)

- Polynomial: O(n²), O(n³), etc.

- Exponential: O(2ⁿ) - typically intractable

When Theory Meets Practice

Questions to ask:

- At what n does this algorithm become too slow?

- Will our business/database ever reach that n?

- Is the simpler O(n²) code better if it’s more maintainable?

- Can we afford the space for the O(n) solution?

- Is the code maintainable and robust?

Example consideration:

- If checking millions of integers and never trillions

- If O(n²) is fast enough (< 10ms) for your use case

- If simpler code reduces bugs and maintenance cost

- Then: O(n²) might be the right choice

Real-World Application: Database Joins

The three approaches to finding duplicates mirror the three main database join algorithms:

- Nested Loop Join: O(n²) - compare everything to everything

- Sort-Merge Join: O(n log n) - sort then merge

- Hash Join: O(n) - build hash table, probe

This pattern appears in many contexts throughout computer science.

Takeaways

- Asymptotic analysis is a tool, not the only consideration

- Theory enables universal conversation about algorithms across decades

- Practice requires system-specific thinking - machine, data, constraints

- Simple code can be better if n is bounded and maintainability matters

- Know when each approach is best:

- Small n, simple code → O(n²) might be fine

- Large n, space available → O(n) hash approach

- Large n, space constrained → O(n log n) sort approach

- Be able to articulate trade-offs in both theoretical and practical terms

- This pattern (nested loops, sort, hash) appears everywhere - recognizing it is valuable

Practice Questions

- Beginner: Which approach do you prefer and why?

- Intermediate: When would you prefer each approach over the others?

- Advanced: Find a clear circumstance where each of the three is better than the other two

Notes on Notation

- The speaker uses “O of n” notation but notes that formal Big O definition will be covered separately

- Focus here is on intuitive understanding of growth patterns

- Complexity classes will be covered in more detail in future videos

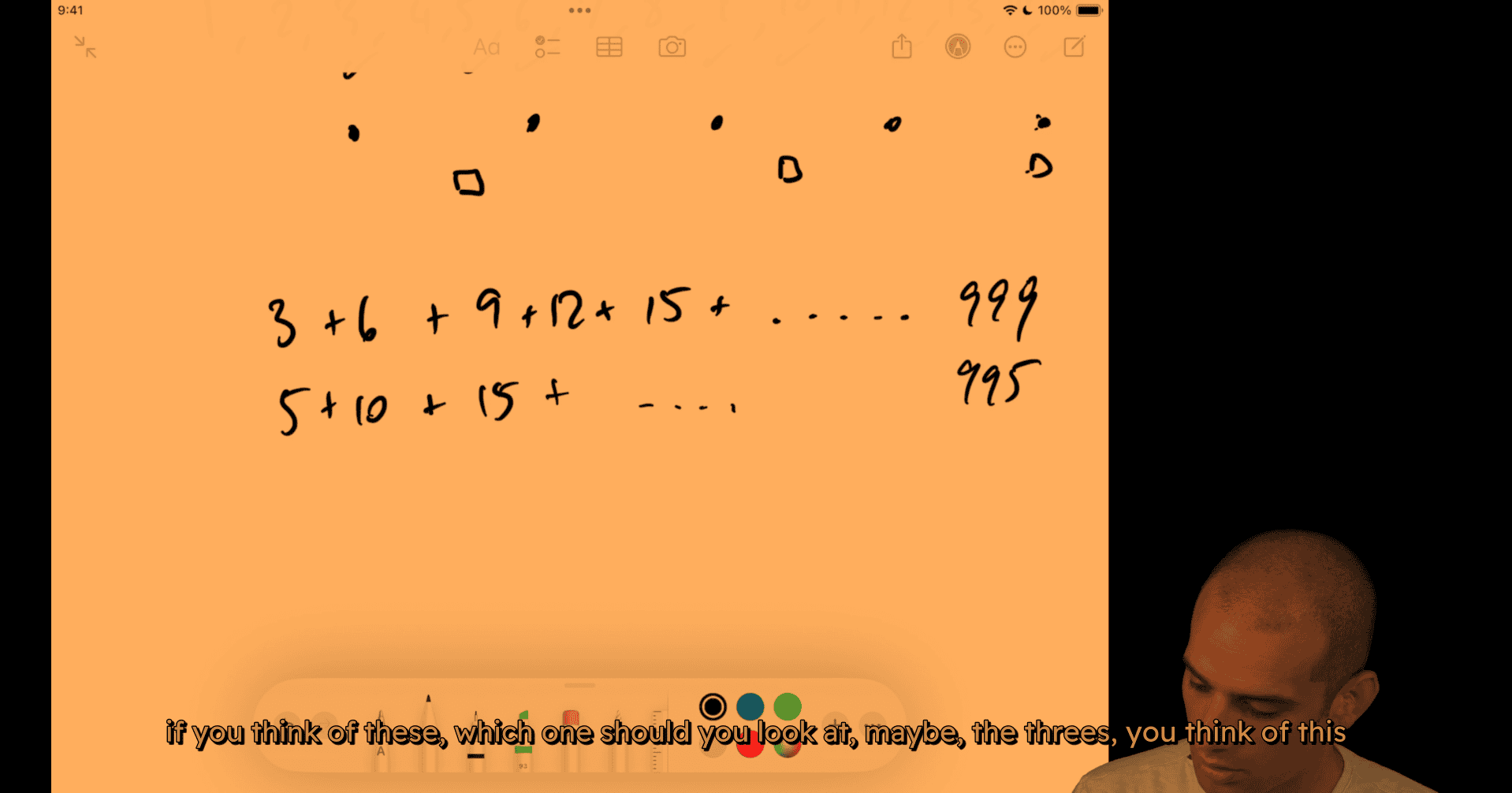

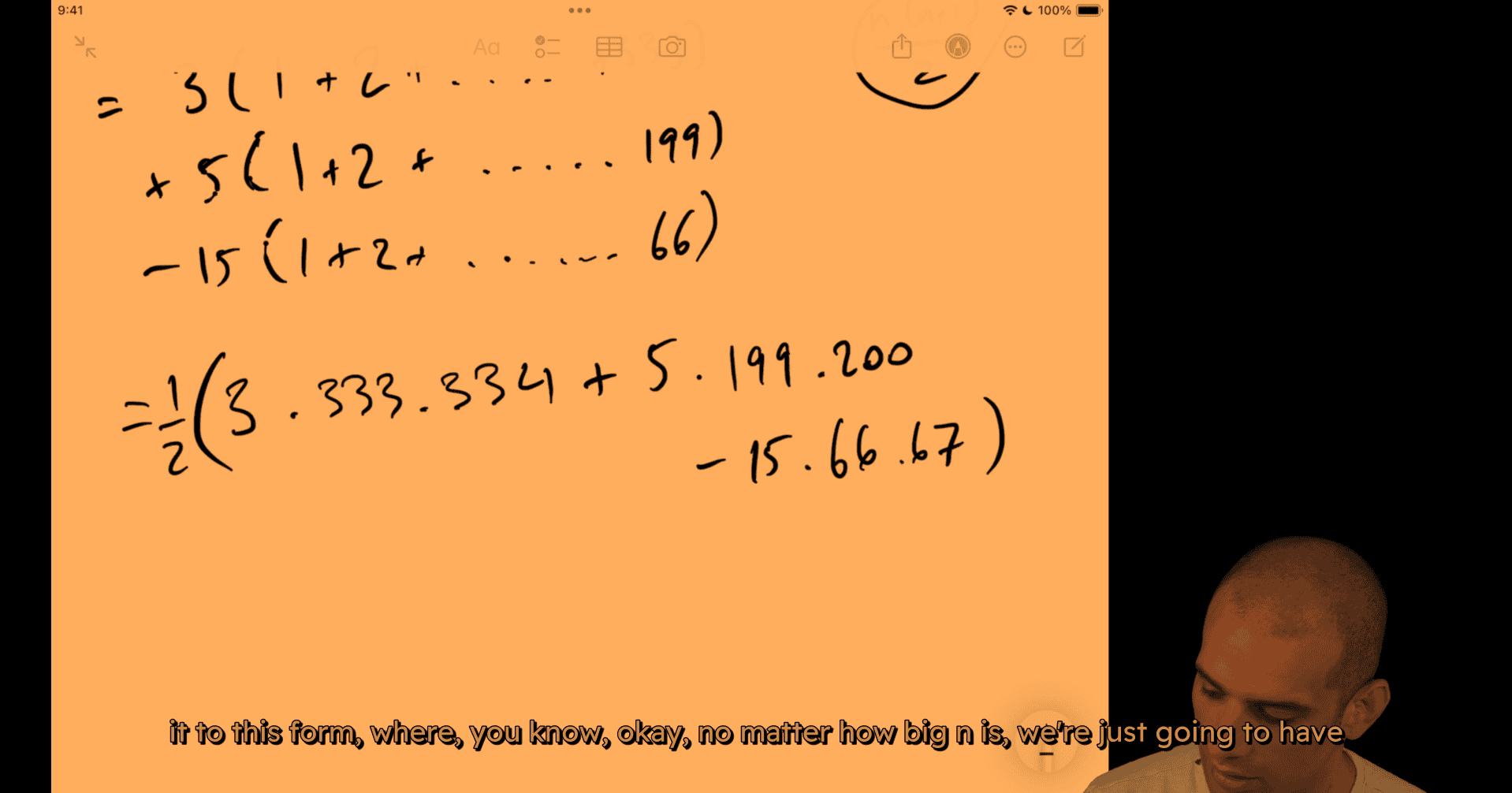

007 Fizzbuzz sum.mp4

Critical question: Do I need to look at every element?

- If yes (e.g., printing FizzBuzz for each number): You’re stuck at O(n)

- If no (e.g., just need the sum): Look for mathematical patterns or closed-form solutions

Within complexity class: You can still optimize constant factors, but for substantial improvement, you need a different complexity class.

with divide and conquer, asking yourself, is there a log time solution to this, would be like saying, could I purchase with divide and conquer, where I divide this into two or more pieces, solve these problems in a way where I can combine the results ?

- the first way that you might want to think about this, you want to try and find a pattern, right, where we can have a mathematical expression for computing that pattern, and so you might

any faster way , pattern?

deduct the repeated part (15 common divider for 3 and 5)

a few multiplications and a few addition subtractions divided by 2, right, n could be billions, constant time solutions

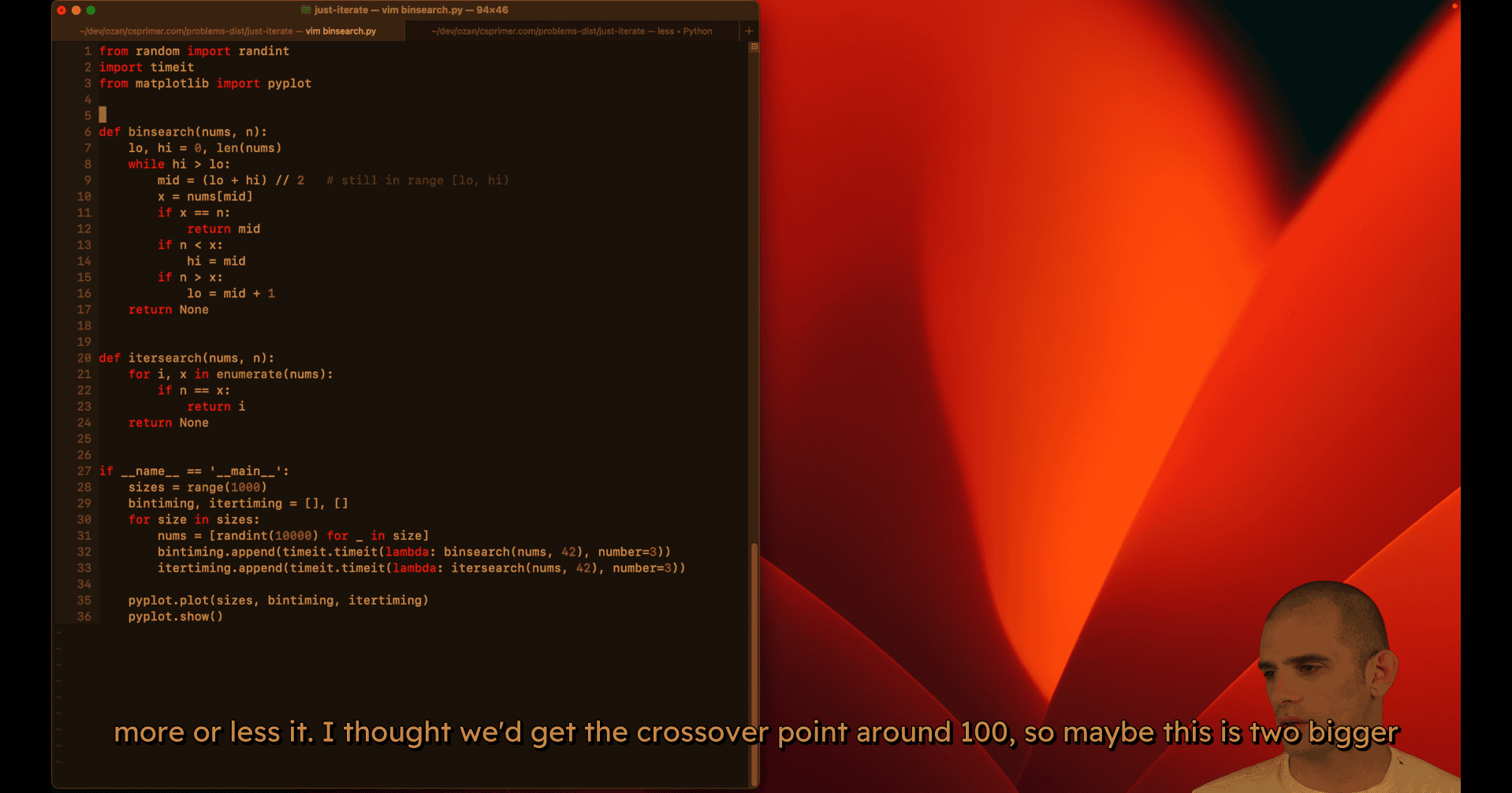

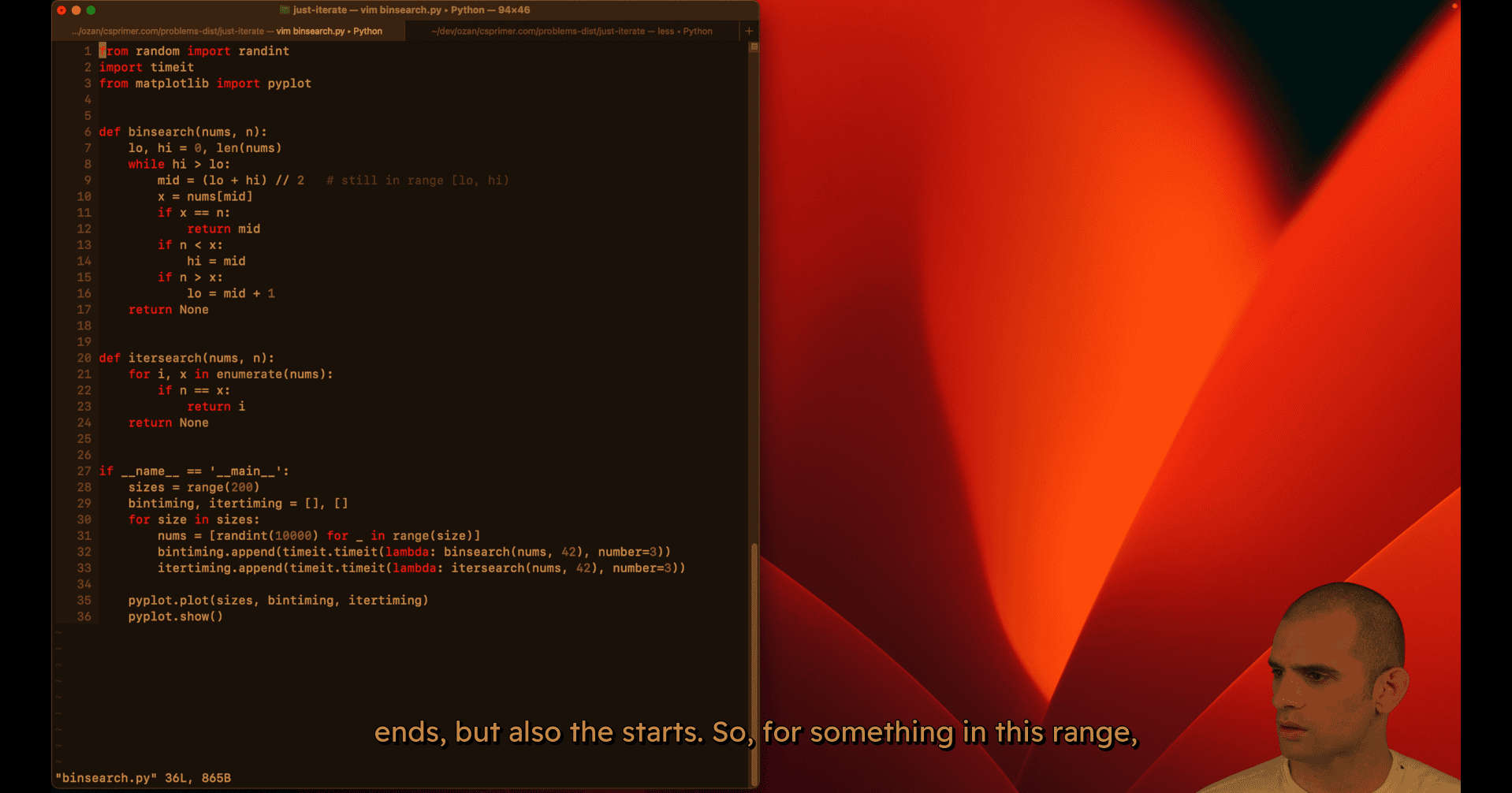

008 Just iterate.mp4

from random import randint

import timeit

from matplotlib import pyplot

def binsearch(nums, n):

lo = 0

hi = len(nums)

while hi > lo:

mid = (lo + hi) // 2 # still in range [lo, hi)

x = nums[mid]

if x == n:

return mid

if n < x:

hi = mid

else:

lo = mid + 1

return None

def itersearch(nums, n):

for i, x in enumerate(nums):

if n == x:

return i

return None

if __name__ == '__main__':

sizes = range(200)

bintiming, itertiming = [], []

for size in sizes:

nums = [randint(0, 10000) for _ in range(size)]

bintiming.append(timeit.timeit(lambda: binsearch(nums, 42), number=3))

itertiming.append(timeit.timeit(lambda: itersearch(nums, 42), number=3))

pyplot.plot(sizes, bintiming, itertiming)

pyplot.show()

009 Analysis practice.mp4

i just skip the video

- Problem: Cut a 3×3×3 cube into 27 unit cubes with minimum cuts

Asymptotic Analysis: Comprehensive Study Notes

Introduction: The Goal of Asymptotic Analysis

Purpose

- Primary goal: Assess the time and space cost, in Big O terms, of most programs you’ll encounter

- Enable comparison of algorithms in a hardware-agnostic way

- Provide a universal language to discuss algorithms across different systems and contexts

- Balance theoretical understanding with practical systems considerations

The Balance: Theory vs. Practice

Theoretical perspective:

- Allows us to say “this algorithm from the 50s is good” in a universal way

- Makes sense regardless of what machine it’s running on

- Enables conversation about algorithms independent of hardware

Practical reality:

- Cannot ignore hardware, data characteristics, or context

- Cannot ignore maintainability of code

- Need both theoretical and systems understanding

The goal: Be comfortable enough with analysis to proceed to graph search, divide-and-conquer, dynamic programming, and extend analysis techniques to those algorithms.

Core Definition: When Is One Algorithm Better?

The Fundamental Question

Given two algorithms, can we say one is objectively better than the other?

Answer: Yes, if there exists some n where one algorithm definitely outperforms the other, regardless of:

- Constant factors

- Hardware differences (Raspberry Pi vs. supercomputer)

- Boot-up time or initialization overhead

Example

- Algorithm A: Linear time (O(n)) on a slow Raspberry Pi

- Algorithm B: Quadratic time (O(n²)) on a supercomputer

Question: Is A better than B?

Answer: Yes! There exists some n where the linear algorithm on the Raspberry Pi will beat the quadratic algorithm on the supercomputer. Eventually, the growth rate dominates.

Key Insight

- Not for every n, but for some n

- Constant factors don’t matter in the limit

- Hardware differences don’t matter in the limit

- The growth pattern (linear vs. quadratic) is what matters

Complexity Classes: The Four Practical Groups

1. Constant-ish

- O(1): Constant time

- O(log n): Logarithmic time

- O(√n): Square root time

Characteristics:

- Effectively “free” or very cheap

- Log n grows extremely slowly (log₂(1000) ≈ 10, log₂(1M) ≈ 20, log₂(1B) ≈ 30)

- Practical systems perspective: these are all “constant-ish”

2. Linear-ish

- O(n): Linear time

- O(n log n): Linearithmic time

Characteristics:

- Scale horizontally: “for every dollar we make, add another server”

- Generally manageable for most applications

- n log n is much closer to linear than to quadratic

3. Polynomial

- O(n²): Quadratic time

- O(n³): Cubic time

- O(nᵏ): Polynomial time for any constant k

Characteristics:

- May need clever optimizations at scale

- At Google scale, might not be affordable

- Generally workable but requires careful consideration

4. Non-Polynomial (Hard Problems)

- O(2ⁿ): Exponential time

- O(n!): Factorial time

Characteristics:

- Effectively impossible for meaningful n

- For exponential: 2⁵⁰ is already intractable

- Cannot use such algorithms in practice

Practical Framing

The four groups help answer:

- Is it effectively free? → Constant-ish

- Can we scale horizontally? → Linear-ish

- Do we need clever optimizations? → Polynomial

- Is it impossible? → Non-polynomial

Units of Measurement

Time Complexity

Unit: Operations

- Could be CPU cycles, seconds, or any consistent unit

- When constant factors are discarded, the exact unit doesn’t matter

- Assumption: Each operation takes consistent time (not always true for big integers, user-defined types, etc.)

Example: Counting function calls

- If each function call takes the same time regardless of input

- Then counting function calls is a valid proxy for time

- Hazard: If function call time varies with input, need to be more careful

Space Complexity

Unit: Memory units

- Could be bytes, stack frames, pages, disk blocks

- Need a consistent unit that grows predictably

Common units:

- Stack frames: For recursive functions, each call uses one stack frame

- Array elements: For data structures, count elements stored

- Bytes: For raw memory usage

Example: Stack space

- Each recursive call pushes a stack frame

- Stack frame size is consistent (contains function locals, return address, etc.)

- Can count stack frames as units of space

Example 1: Constant Time Operations

Simple Multiplication

def multiply(a, b):

return a * bTime Complexity: O(1)

- One operation (multiplication)

- Irrespective of input size

Assumptions:

- Integers are primitive types (fit in CPU registers)

- Multiplication is a single CPU instruction

- Not Python big integers (arbitrarily sized)

- Not user-defined types with custom

__mul__methods

When assumptions break:

- Python big integers: multiplication time grows with number size

- Cryptographic operations: multiplying huge primes is not constant

- User-defined types:

__mul__could do anything

Key takeaway: Always consider what assumptions you’re making about input types and operations.

Example 2: Square Root Functions

Built-in Square Root

import math

def sqrt_builtin(n):

return math.sqrt(n)Time Complexity: Depends on implementation

- If hardware floating-point: O(1) - constant time

- If software implementation: Could be O(log n) or O(√n)

Binary Search Square Root

def sqrt_binary_search(n):

# Binary search for k such that k² ≤ n < (k+1)²

left, right = 1, n

while left < right:

mid = (left + right) // 2

if mid * mid <= n:

left = mid + 1

else:

right = mid

return left - 1Time Complexity: O(log n)

- Binary search over space from 1 to n

- Each iteration halves the search space

Linear Search Square Root

def sqrt_linear(n):

k = 1

while k * k <= n:

k += 1

return k - 1Time Complexity: O(√n)

- Tries 1², 2², 3², … until finding the answer

- Terminates early at √n iterations

Comparison: O(log n) vs. O(√n)

Theoretical: O(log n) is better (lower complexity class)

Practical considerations:

- Constant factors: Binary search has branch prediction overhead

- Threshold: At n = 64, √64 = 8, log₂(64) = 6

- Real systems: May need to benchmark to determine which is actually faster

- Interview perspective: Want to hear about systems considerations, not just “I’d benchmark”

Key insight: Sometimes O(log n) vs. O(√n) are close enough that constant factors and systems considerations matter more than the theoretical difference.

Example 3: Factorial - Recursive vs. Iterative

Recursive Factorial

def factorial_recursive(n):

if n <= 1:

return 1

return n * factorial_recursive(n - 1)Time Complexity: O(n)

- Makes n function calls (n, n-1, n-2, …, 1)

- Each call does one multiplication

- Total: n multiplications

Space Complexity: O(n)

- Each recursive call uses one stack frame

- Maximum stack depth: n

- Total: n stack frames

Call chain: Linear chain, not a tree

- factorial(10) → factorial(9) → factorial(8) → … → factorial(1)

- Just a straight line, not branching

Iterative Factorial

def factorial_iterative(n):

result = 1

for i in range(1, n + 1):

result *= i

return resultTime Complexity: O(n)

- Loop runs n times

- Each iteration: one multiplication

- Total: n multiplications

Space Complexity: O(1)

- Only one accumulator variable

- No stack frames

- Constant space

Comparison

Time: Both O(n) - same asymptotic complexity

Space:

- Recursive: O(n) - stack frames

- Iterative: O(1) - constant space

Practical speed: Iterative is typically faster

- No function call overhead

- No stack frame allocation

- But both are O(n), so this is just a constant factor difference

Tail Call Optimization

What Is Tail Call Optimization?

Tail position: The very last operation in a function, with nothing after it

Tail call: A recursive call in tail position

Tail call optimization (TCO): Compiler/interpreter optimization that converts tail-recursive functions to iterative form automatically

Example: Non-Tail Recursive

def factorial_recursive(n):

if n <= 1:

return 1

return n * factorial_recursive(n - 1) # NOT tail positionWhy not tail?: After the recursive call returns, we still need to multiply by n

Converting to Tail Recursive

def factorial_tail_recursive(n, accumulator=1):

if n <= 1:

return accumulator

return factorial_tail_recursive(n - 1, n * accumulator) # Tail positionNow it’s tail recursive: The recursive call is the very last thing, nothing happens after it

Benefits of TCO

- Space: O(n) → O(1) (no stack frames needed)

- Speed: Eliminates function call overhead

- Automatic: Compiler/interpreter handles the conversion

Languages with TCO

- LISP: Heavily recursive, TCO is standard

- JavaScript: V8 and other engines support TCO (but not in spec)

- Python: Does NOT support TCO (by design choice)

Key insight: If you can write tail-recursive code, TCO can give you the benefits of iteration (O(1) space) while keeping recursive code structure.

Example 4: Fibonacci - Multiple Approaches

Naive Recursive Fibonacci

def fib_naive(n):

if n <= 1:

return n

return fib_naive(n - 1) + fib_naive(n - 2)Time Complexity: O(2ⁿ)

- Tree structure: Each call branches into two subproblems

- Height: Approximately n (from n down to base cases)

- Branching factor: 2 (each node has 2 children)

- Total nodes: Approximately 2ⁿ

- Tighter bound exists: But O(2ⁿ) is a valid upper bound

Why exponential?

- fib(10) calls fib(9) and fib(8)

- fib(9) calls fib(8) and fib(7)

- fib(8) is computed twice (once from fib(10), once from fib(9))

- Massive redundant computation

Space Complexity: O(n)

- Stack depth: Maximum depth is n (one path from root to leaf)

- Not O(2ⁿ): Stack shrinks and grows, never exceeds n

- Even though we make 2ⁿ function calls, we don’t need 2ⁿ stack frames simultaneously

Memoized Fibonacci

def fib_memoized(n, memo={}):

if n in memo:

return memo[n]

if n <= 1:

return n

memo[n] = fib_memoized(n - 1, memo) + fib_memoized(n - 2, memo)

return memo[n]Time Complexity: O(n)

- Unique subproblems: Only n unique values (0, 1, 2, …, n)

- Each computed once: After first computation, cached result is reused

- Total work: n function calls, each doing O(1) work (after memoization)

Space Complexity: O(n)

- Memo cache: Stores n values (0 through n)

- Stack depth: Still O(n) maximum

- Total: O(n) space

Key insight: Memoization eliminates redundant subproblem computation by caching results.

Bottom-Up Dynamic Programming

def fib_bottom_up(n):

if n <= 1:

return n

a, b = 0, 1

for i in range(2, n + 1):

a, b = b, a + b

return bTime Complexity: O(n)

- Loop runs n-1 times

- Each iteration: constant work (addition, assignment)

- Total: O(n)

Space Complexity: O(1)

- Key insight: Only need the last two values

- State: Two integers (a and b)

- No array needed: Don’t need to store all previous values

- No stack: Iterative, not recursive

Comparison to memoized:

- Time: Both O(n) - same

- Space: Bottom-up is O(1) vs. O(n) for memoized

- Why better?: Recognized that only recent state (last 2 values) is needed

The Progression

- Naive recursive: O(2ⁿ) time, O(n) space - exponential, unusable

- Memoized: O(n) time, O(n) space - linear, much better

- Bottom-up: O(n) time, O(1) space - optimal for this problem

Key lesson: After fixing time complexity, can often optimize space by recognizing what state is actually needed.

Practical Considerations

When Constant Factors Matter

Examples:

- Branch prediction: Binary search has unpredictable branches

- Function call overhead: Recursive calls have overhead

- Cache locality: Array access patterns affect performance

- Memory allocation: Dynamic allocation has overhead

When to benchmark:

- Complexity classes are close (e.g., O(log n) vs. O(√n))

- Constant factors might dominate for your n

- Need to understand systems-level behavior

Not enough to just benchmark: Need to understand why one might be faster/slower to validate your benchmark.

Making Assumptions

Always need to state assumptions:

- Input types (integers, not big integers)

- Operation costs (multiplication is constant)

- System characteristics (stack frame size, etc.)

When assumptions break:

- Python big integers: operations grow with size

- User-defined types: could have arbitrary behavior

- Dynamic languages: types unknown until runtime

Key: Be explicit about assumptions, especially in interviews or documentation.

Industry Usage

Common vocabulary:

- “This is O(n²)” - frequently used

- “Polynomial time solution” - used

- “Exponential, can’t use this” - used

Rarely used:

- Θ (theta) - tight bound notation

- Ω (omega) - lower bound notation

- o (little-o) - strict upper bound

- Formal mathematical definitions

Practical focus: Big O for upper bounds, complexity classes, and trade-off discussions.

Common Use Cases

Database operations:

- Join algorithms: nested loop (O(n²)) vs. hash join (O(n)) vs. sort-merge (O(n log n))

- Index selection: affects query complexity

- Query optimization: choosing algorithms based on data size

Data processing:

- GraphQL resolvers: combining data from multiple sources

- ETL pipelines: processing large datasets

- Real-time systems: latency requirements

Key question: At what scale does this algorithm become too slow?

Key Takeaways

1. Asymptotic Analysis Is a Tool

- One tool in your toolkit, not the only consideration

- Enables universal conversation about algorithms

- Must be balanced with systems knowledge

2. The Core Definition

- Algorithm A is better than B if there exists some n where A outperforms B

- Constant factors and hardware don’t matter in the limit

- Growth pattern (linear, quadratic, exponential) is what matters

3. Complexity Classes

- Constant-ish: O(1), O(log n), O(√n) - effectively free

- Linear-ish: O(n), O(n log n) - scale horizontally

- Polynomial: O(n²), O(n³) - may need optimization

- Non-polynomial: O(2ⁿ), O(n!) - effectively impossible

4. Units Matter

- Time: Operations (CPU cycles, function calls, etc.)

- Space: Memory units (stack frames, array elements, bytes)

- Need consistent units that grow predictably

5. Optimization Strategies

- Memoization: Cache subproblem results → reduces redundant computation

- Bottom-up DP: Build solutions iteratively, recognize minimal state needed

- Tail call optimization: Convert tail-recursive to iterative automatically

6. Practical Balance

- Theory enables universal discussion

- Practice requires systems knowledge

- Sometimes need to benchmark (especially when complexity classes are close)

- Constant factors matter in real systems

7. Common Patterns

- Recursive → Iterative: Often improves space from O(n) to O(1)

- Naive → Memoized: Eliminates redundant computation

- Memoized → Bottom-up: Can reduce space by recognizing minimal state

Practice Problems

Beginner

- What’s the time and space complexity of a simple loop that sums an array?

- Compare recursive vs. iterative factorial implementations.

- Why is naive Fibonacci O(2ⁿ) but memoized is O(n)?

Intermediate

- Convert a tail-recursive function to iterative form.

- Optimize a memoized solution to use O(1) space when possible.

- Analyze the square root binary search vs. linear search trade-offs.

Advanced

- Find a tighter bound than O(2ⁿ) for naive Fibonacci (hint: consider early termination).

- Implement tail call optimization manually using a trampoline pattern.

- Analyze space complexity of recursive algorithms with branching (when is it O(depth) vs. O(nodes)?)

Additional Notes

The Cube Cutting Problem (Brain Teaser)

- Problem: Cut a 3×3×3 cube into 27 unit cubes with minimum cuts

- Key insight: Consider the innermost cube - it requires 6 cuts (one per face)

- Technique: Simplify by discarding pieces, focus on the piece requiring most work

- Answer: Minimum is 6 cuts (cannot be done in fewer)

Stretch Goals

- Find tighter bounds for Fibonacci (better than O(2ⁿ))

- Analyze when tail call optimization can be applied automatically

- Understand trampoline pattern for manual TCO

Resources for Further Study

- Donald Knuth’s “The Art of Computer Programming”

- Formal definitions of Big O, Θ, Ω notation

- Systems-level performance analysis (branch prediction, cache locality)

- Compiler optimizations (TCO, inlining, etc.)

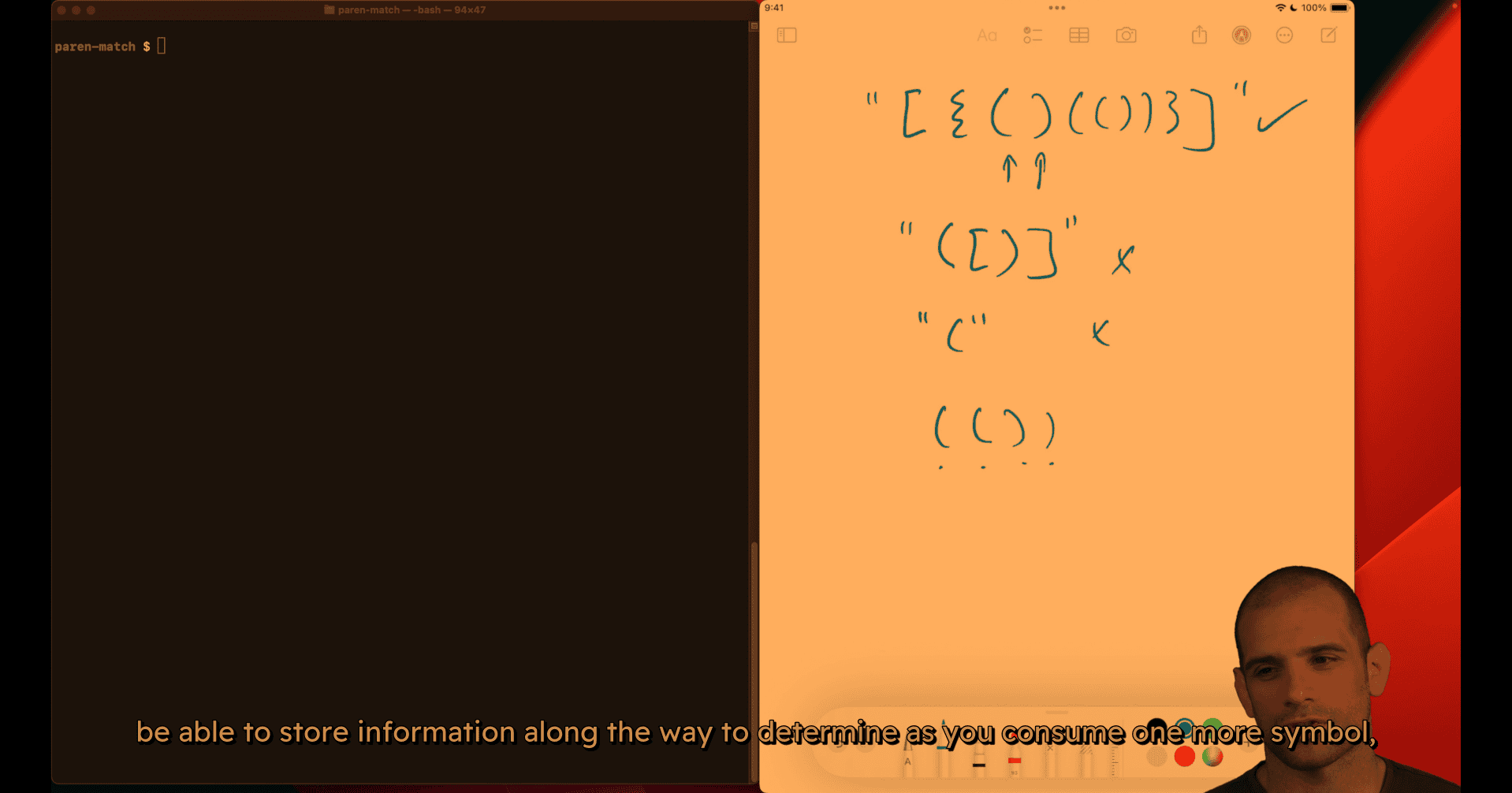

015 Parenthesis match.mp4

So, queues are intuitive like that, hopefully you’re processing things in order. buffer, you can kind of think of that as a queue of bytes.

stack: do the opposite of a queue, which is to process something in the opposite order. we want to work in the order of the things most recently visited as a priority

“Do I need to access things in reverse order of when I encountered them?”

If yes → Use a stack!

- plan

- small case

primer will state clear the test case , and even name the error case name ‘categorical thinking’

of the reason why this is false. I just like being categorical and having a kind of model type of error and so on in the test cases.

step1 :

step 2 :

matches left:

up in our dictionary is not equal to the new value, then we have a mismatch. Maybe actually

up in our dictionary is not equal to the new value, then we have a mismatch. Maybe actually

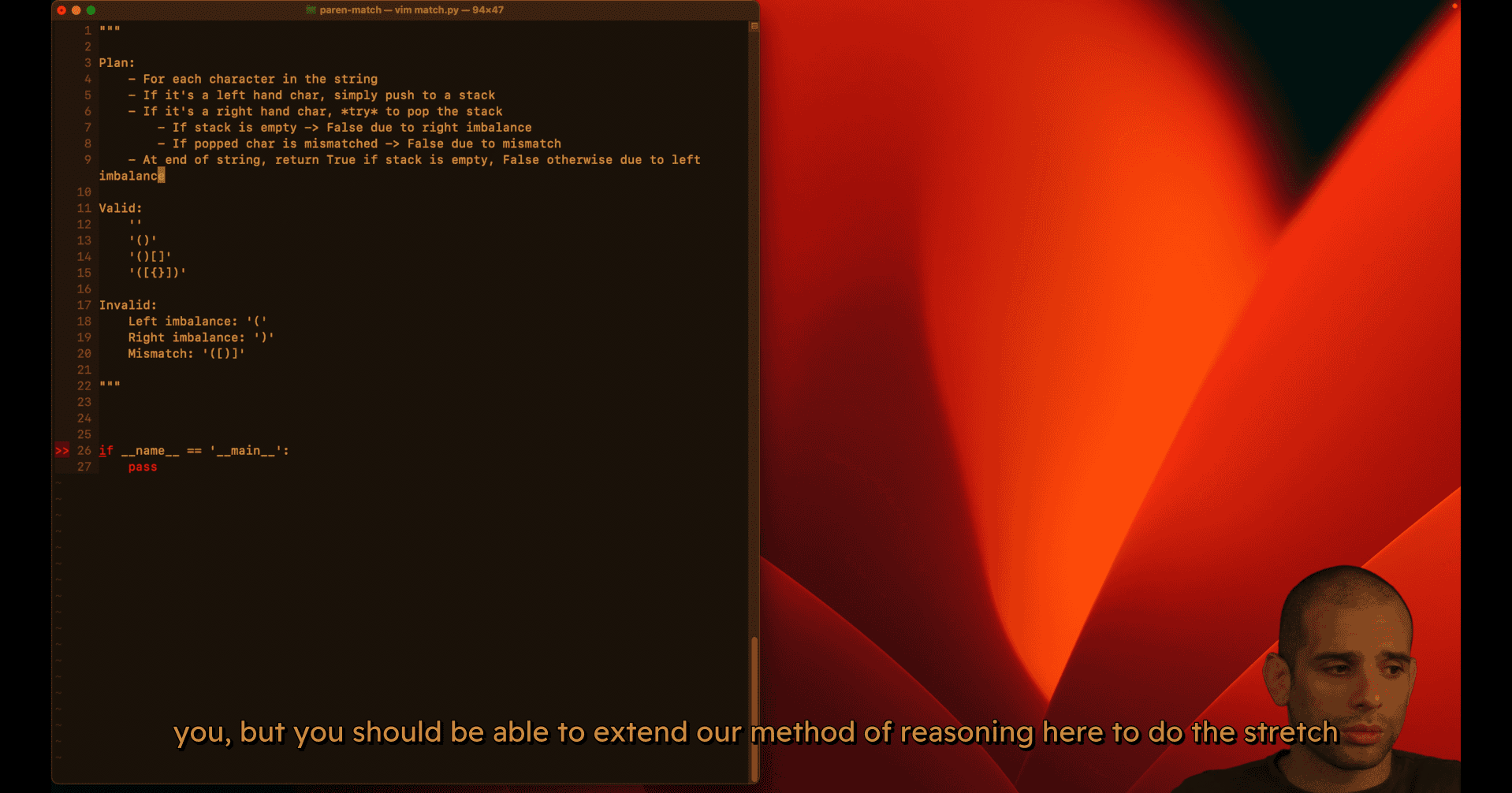

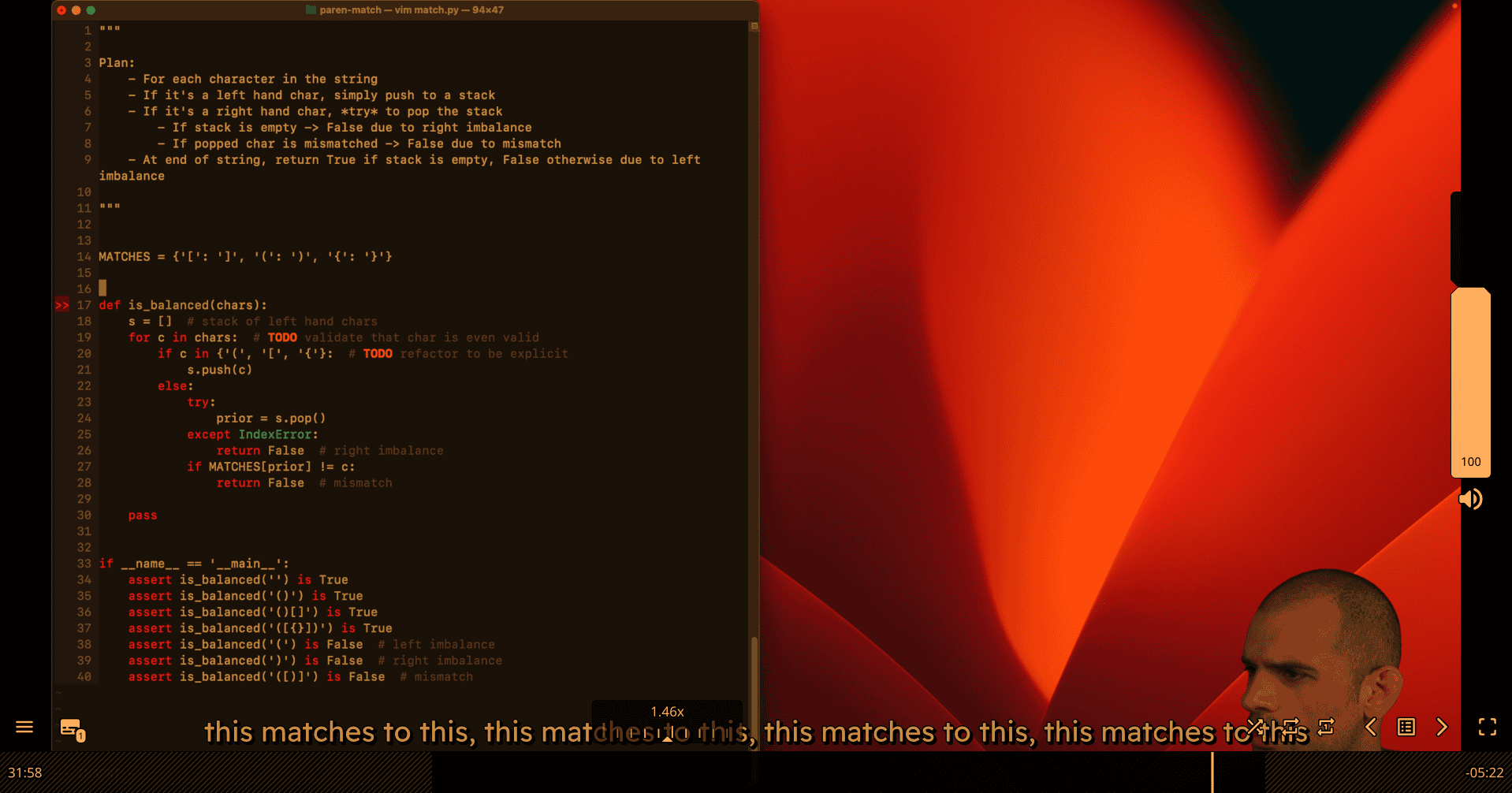

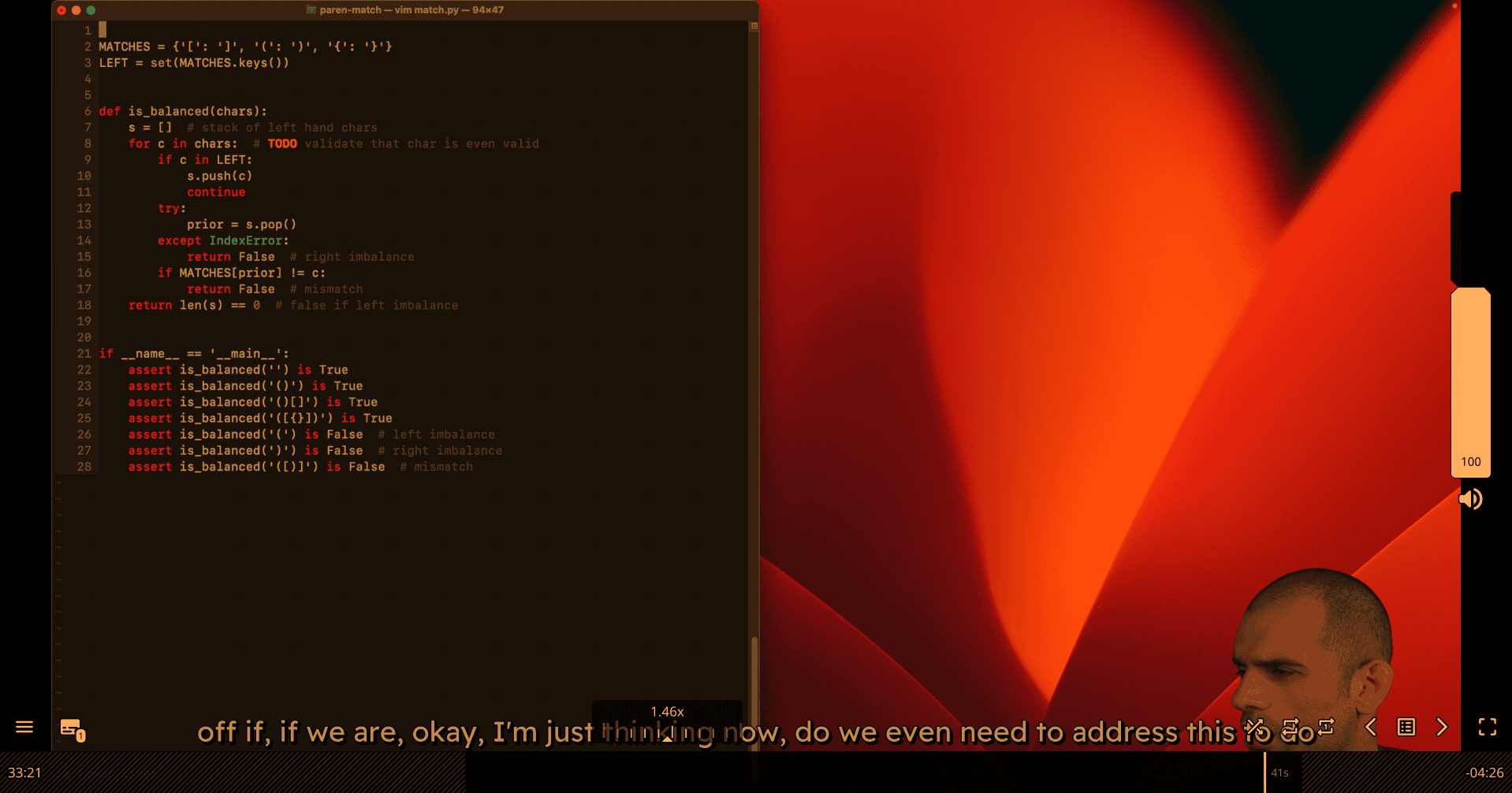

"""

Parenthesis Matching Implementation

Based on the algorithm plan from the lecture

"""

MATCHES = {'[': ']', '(': ')', '{': '}'}

LEFT = set(MATCHES.keys())

RIGHT = set(MATCHES.values())

def is_balanced(chars):

"""

Plan:

- For each character in the string

- If it's a left hand char, simply push to a stack

- If it's a right hand char, *try* to pop the stack

- If stack is empty -> False due to right imbalance

- If popped char is mismatched -> False due to mismatch

- At end of string, return True if stack is empty, False otherwise due to left imbalance

"""

s = [] # stack of left hand chars

for c in chars: # TODO: validate that char is even valid

if c in LEFT:

s.append(c) # Fixed: Python lists use append(), not push()

continue

if c not in RIGHT: # Space case

continue

try:

prior = s.pop()

except IndexError:

return False # right imbalance

if MATCHES[prior] != c:

return False # mismatch

return len(s) == 0 # false if left imbalance

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Valid cases

assert is_balanced('') is True

assert is_balanced('()') is True

assert is_balanced('()[]{}') is True

assert is_balanced('({[]})') is True

# Invalid cases

assert is_balanced('(') is False # left imbalance

assert is_balanced(')') is False # right imbalance

assert is_balanced('([)]') is False # mismatch

print("All tests passed!")

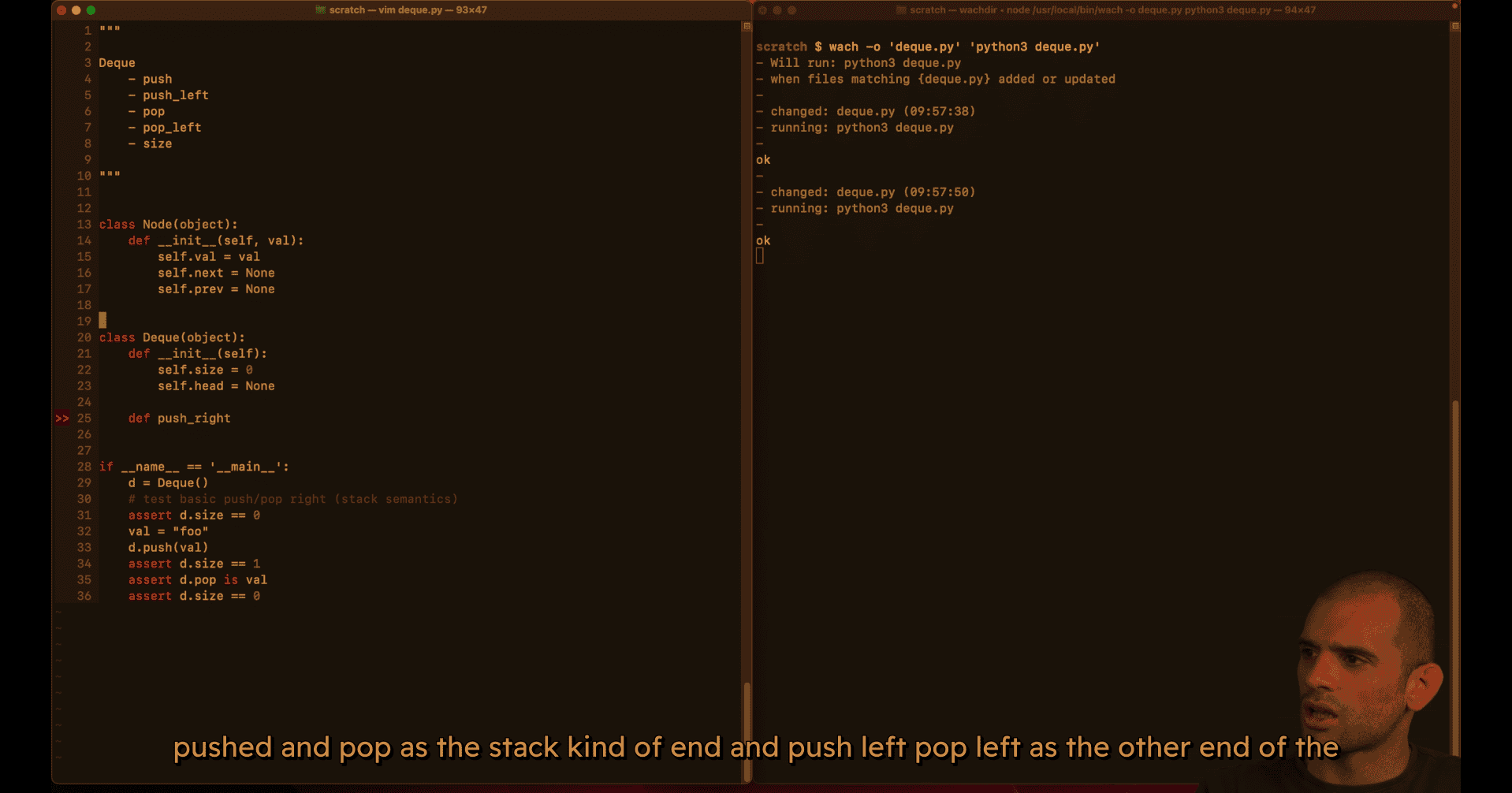

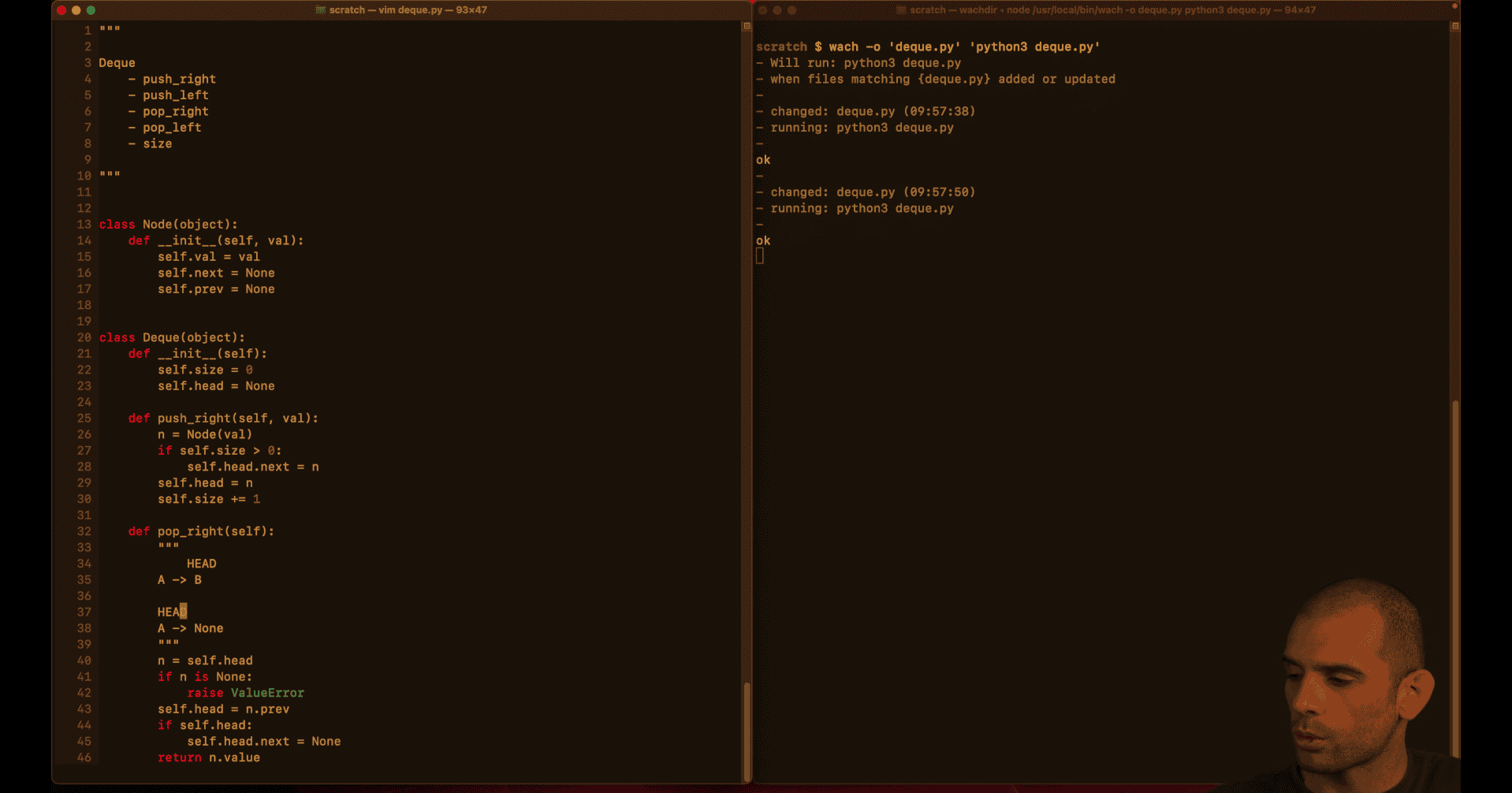

016 Doubly linked list.mp4

using comment to show the mvp e.g.

double linked list: head become tail, next become prev

- empty case

/home/peter/Desktop/cursor_project/doubly-linked-list-notes.md

Memory Management: Critical Considerations

The Problem: Circular References

Circular reference example:

## Node A points to Node B

A.next = B

B.prev = A

## Even if nothing else references A or B,

## they still reference each other!

## Reference count never drops to zeroIn Python:

- Reference counting: Fast, but fails with circular references

- Tracing garbage collection: Slow, but handles circular references

- Best practice: Break references explicitly to avoid circular references

Solution: Always Break Links

When removing a node:

- Set

next = Noneon the node before it - Set

prev = Noneon the node after it - Update head/tail appropriately

- Set head/tail to None when deque becomes empty

Example in pop_right:

self.head = n.prev # Move head back

if self.head is not None:

self.head.next = None # Break forward link (critical!)

else:

self.tail = None # Also clear tail if emptyWhy This Matters

Long-running processes:

- Servers, databases, web applications

- Memory leaks accumulate over time

- Can cause performance degradation or crashes

Best practice:

- Always set pointers to

Nonewhen removing nodes - Be explicit about breaking references

- Test that memory is properly reclaimed

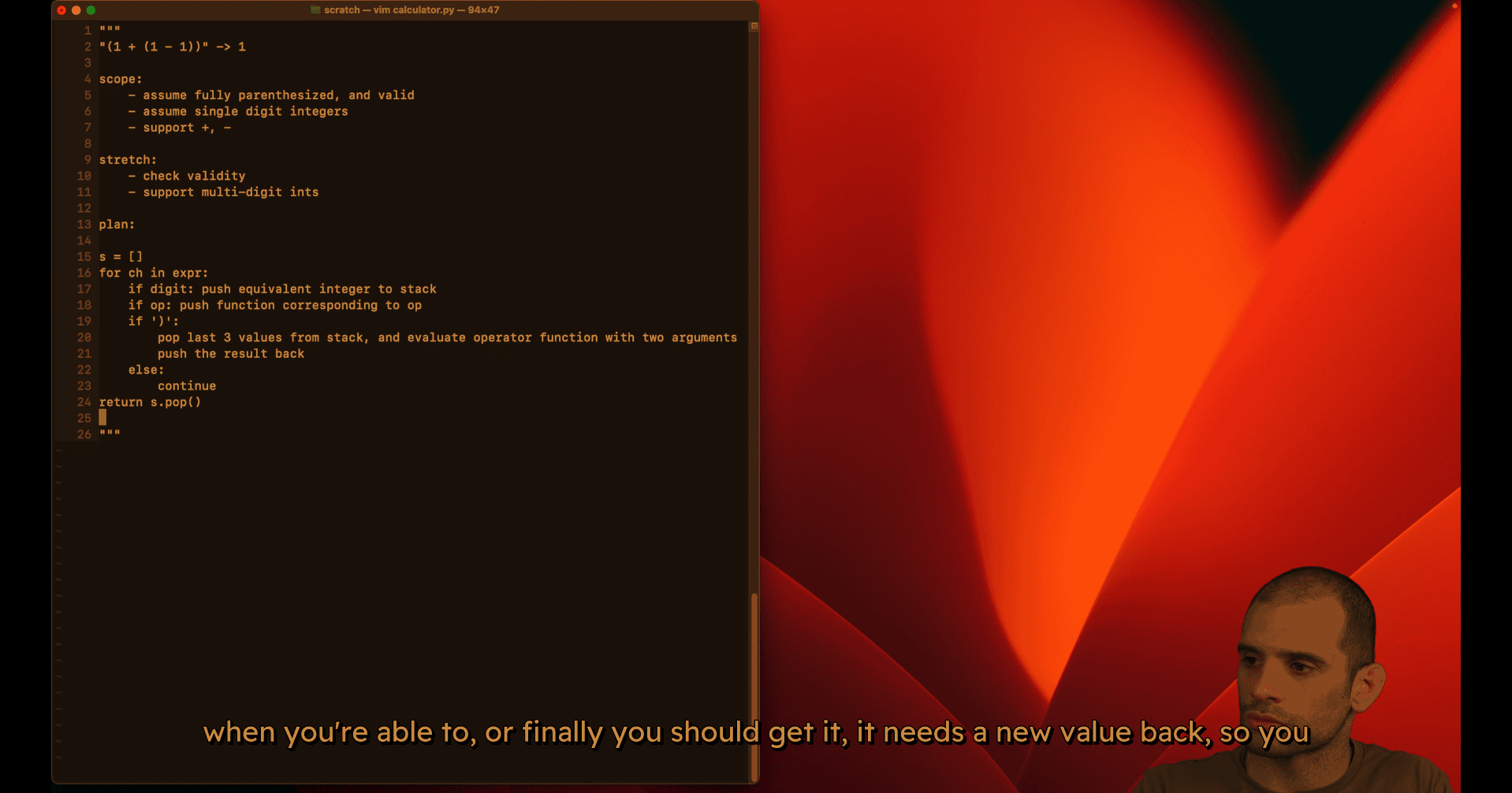

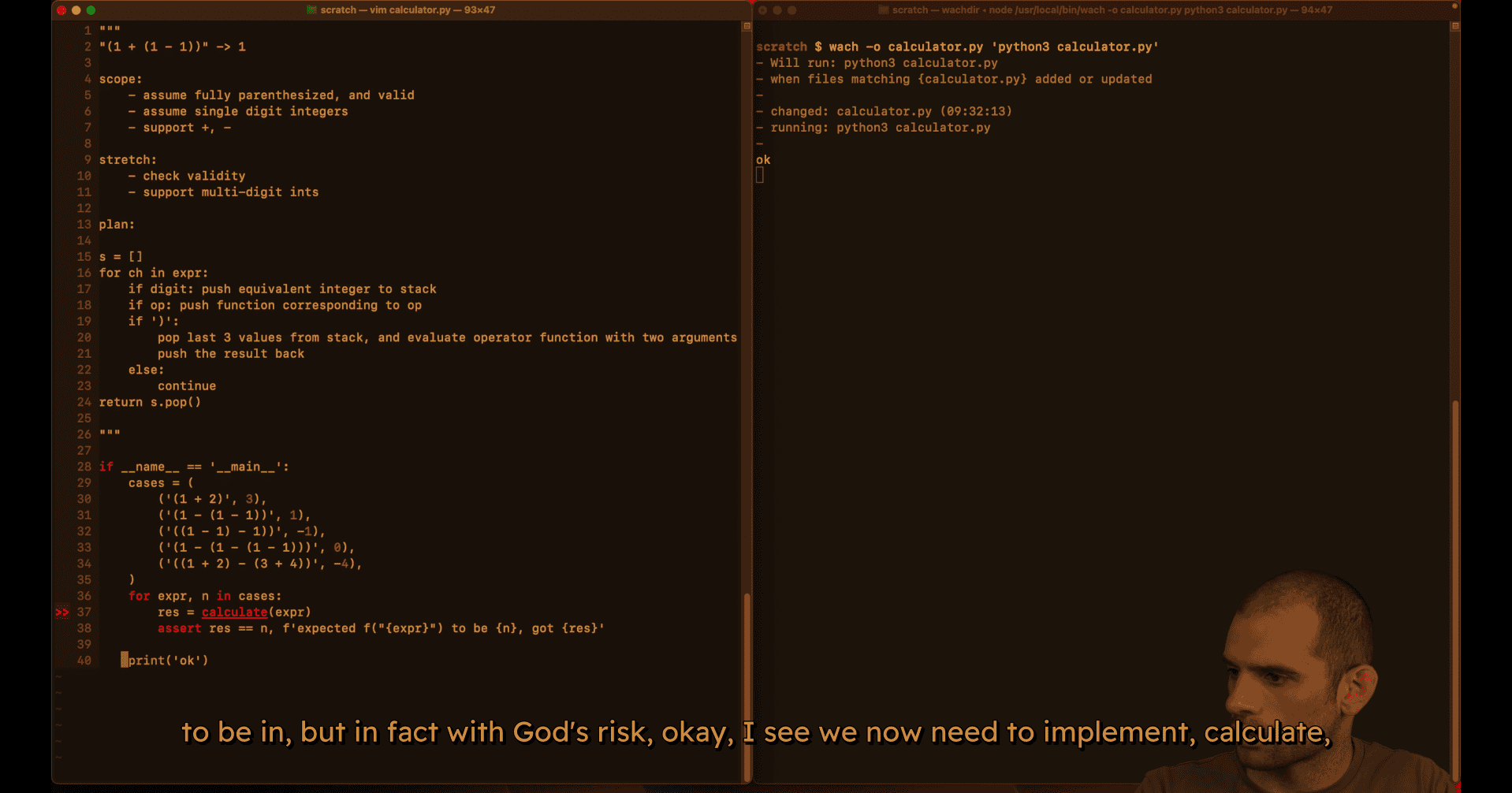

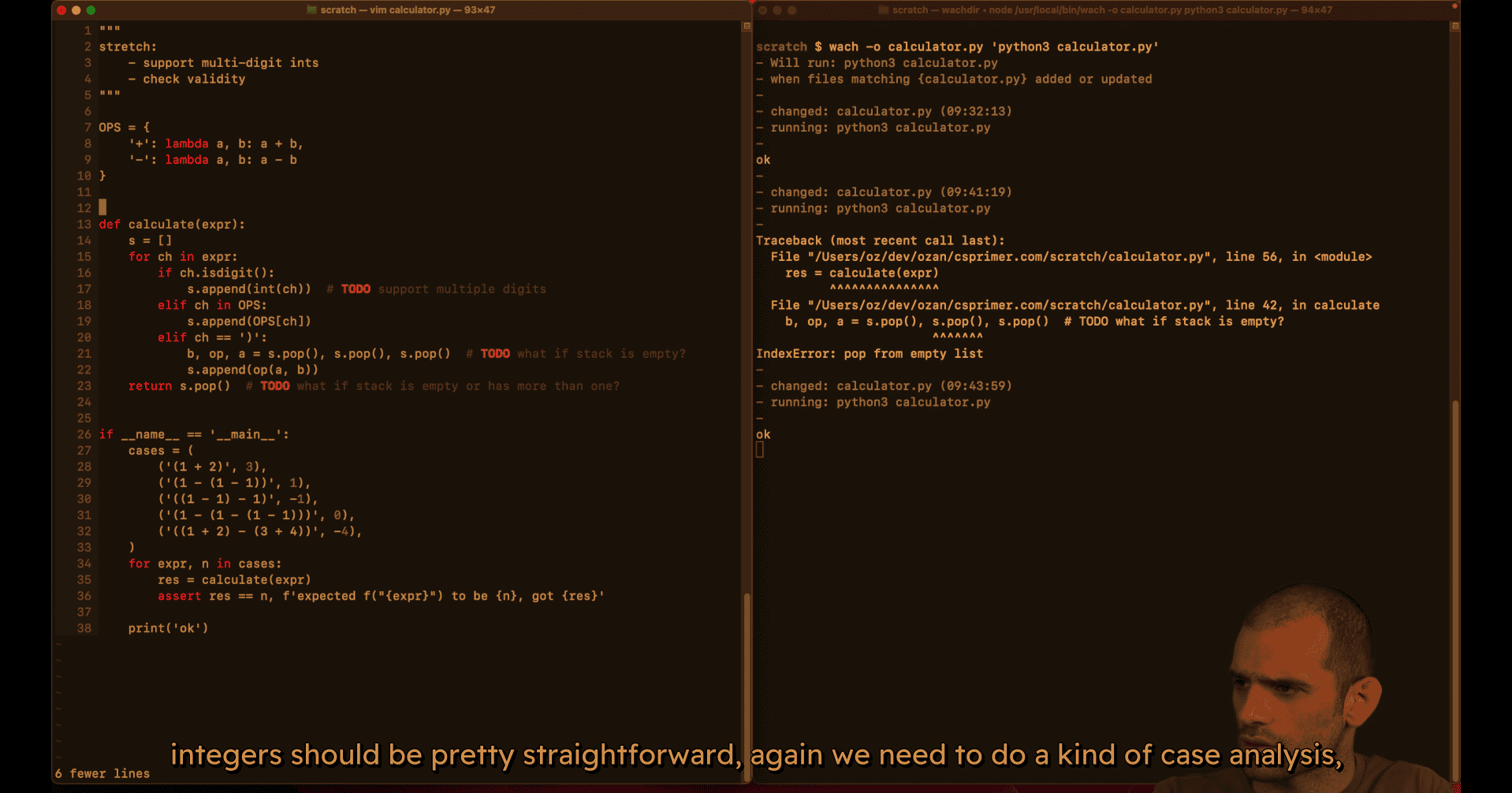

017 Basic calculator.mp4

plan :

test case:

mvp (single digit mode work)

primer logic for double digit :

if len(is) == 0 or not isinstance(s[-i],int):

s.append(int(ch))

else:

s[-1]=s[-1]*10+int(ch)gpt logic:

# Combine with previous digit if present (multi-digit support)

if stack and isinstance(stack[-1], int):

stack[-1] = stack[-1] * 10 + digit

else:

stack.append(digit)